A Strange Sort of Warfare Underground: Mines and Countermines on the Petersburg Front, 1864.

A paper by Julia Steele, Philip Shiman, and David Lowe, presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology annual meeting, January 2016, Washington, DC.

The definition of undermine is to “dig or excavate beneath a building or fortification so as to make it collapse”. A secondary meaning is: …”to damage or weaken someone or something, especially gradually or insidiously” (Merriam’s online dictionary). An unspoken aspect is that undermining is done in secrecy: the intended victim is in the dark in terms of when or where the aggressor will strike. The aggressor is literally in the dark, as they pursue an underground course towards the enemy’s defenses.

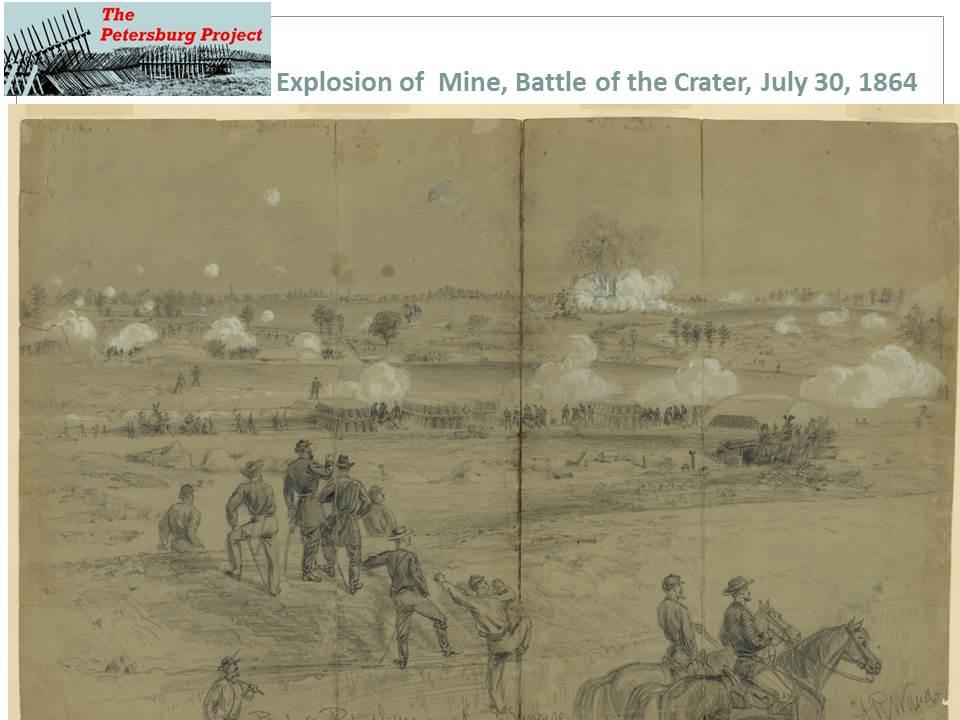

Petersburg National Battlefield, Virginia, is known for the explosion, detonated from an underground tunnel, or mine, which destroyed a Confederate fort and initiated the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864, during the American Civil War.

Petersburg National Battlefield, Virginia, is known for the explosion, detonated from an underground tunnel, or mine, which destroyed a Confederate fort and initiated the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864, during the American Civil War.

Technically, the mining effort to reach the opponent’s line was itself a great success, but the follow through was a failure when the Federals were not able take advantage of the massive explosion to break through and capture the heights above Petersburg, or the city itself. This was not the only tunnel excavated on the lines between the two armies, which eventually stretched from north of the Confederate capital of Richmond, to west of the critical rail and manufacturing center of Petersburg, twenty five miles south of Richmond.

Even before the July 30, 1864, explosion, the Confederate defenders of Petersburg constructed countermines in places where the terrain was susceptible to underground enemy approaches. Federal engineers also constructed countermines and listening galleries or listening wells in locations where they suspected their opponent might make use of underground approaches. Although each side suspected the other was constructing mines, by their very nature these structures were hidden, their locations unknown to most of the miners’ compatriots. With the exception of the famous Crater mine, which became part of a tourist attraction after the war, Petersburg residents either never knew, or lost sight of the locations of the mines. Two sets of tunnels were found serendipitously during the twentieth century- one when a mule pulling a plow disappeared into a hole in the earth, and the other during construction activities in the 1970s.

Even before the July 30, 1864, explosion, the Confederate defenders of Petersburg constructed countermines in places where the terrain was susceptible to underground enemy approaches. Federal engineers also constructed countermines and listening galleries or listening wells in locations where they suspected their opponent might make use of underground approaches. Although each side suspected the other was constructing mines, by their very nature these structures were hidden, their locations unknown to most of the miners’ compatriots. With the exception of the famous Crater mine, which became part of a tourist attraction after the war, Petersburg residents either never knew, or lost sight of the locations of the mines. Two sets of tunnels were found serendipitously during the twentieth century- one when a mule pulling a plow disappeared into a hole in the earth, and the other during construction activities in the 1970s.

This paper will discuss how the use of LIDAR imagery, map and photographic analysis, documentary research, and field survey revealed two forgotten but extensive sets of underground tunnels in front of Confederate positions within Petersburg National Battlefield. Fresh analysis of the tunnels and other military features enables a better understanding of the fierce struggles along the seemingly static front and the array of measures, including sharpshooting, sapping, land mines, grenades and water obstacles, used to counter and outwit the enemy. The Confederates actually detonated explosives in one set of tunnels and created “craters” that may be still evident on the landscape. The effort put in to these underground passages is testament to the importance of the salients to Confederate defenses and to their vulnerability.

Engineering reports on both sides, published in the Official Reports of the War of the Rebellion outline the progress of tunneling efforts by the combatants and such efforts are noted in memoirs and letters, yet many of these features remained obscured by post war processes as the battle torn landscape was returned to production or became reforested. Federal mines and countermines were duly noted on the extensive maps prepared by the Union topographic engineers.

After portions of the battlefield were preserved as a national military park beginning in the 1920s, the famous Crater mine was preserved, and even excavated by archeologists on several occasions (Blades 2001). A countermine running out towards the Confederate lines from Federal Fort Stedman was inadvertently uncovered in the 1930s. Artifacts such as a “Shovel, bayonets, rifle parts, a cartridge box” were allegedly removed from the intact feature before it was resealed, but no photographs, reports or other documentation have been found aside from an article in the local paper (Hess 2009:293). Modern historians, including Earl Hess and Harry Jackson, discuss the mines and countermines in detail, but do not locate most of them on the modern landscape, nor does Brooke Blades in the 2001 Archeological Overview and Assessment of the Main Unit, Petersburg National Battlefield.

To return to 1864, Brigadier General Johnson Hagood, C.S.A., outlines the use of countermines by the Confederate defenders:

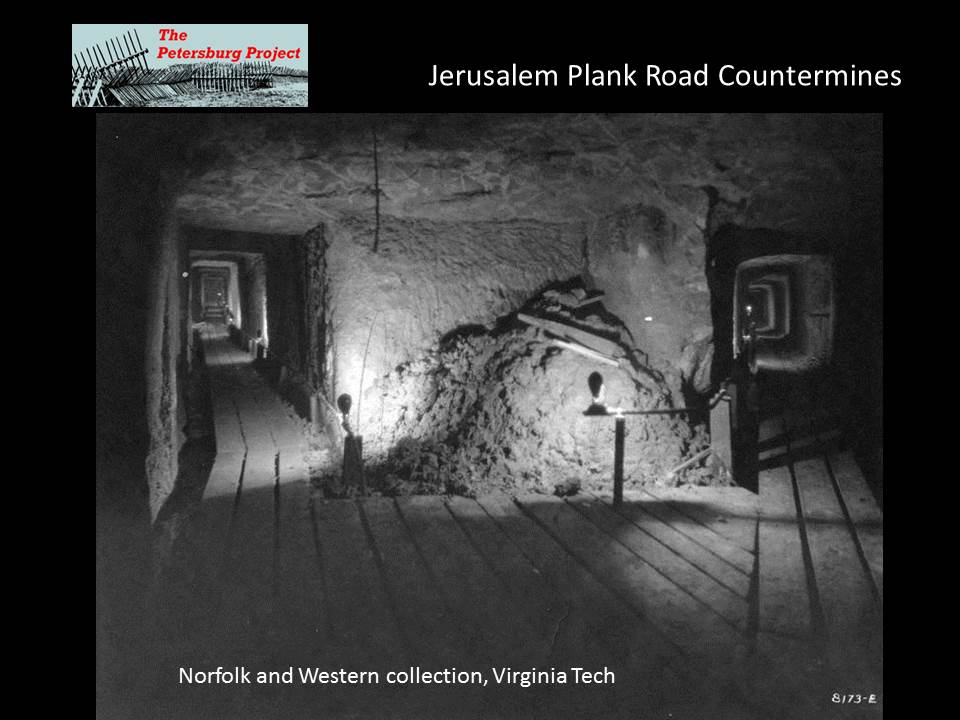

Accordingly, counter mines were commenced at the points where the hostile lines were nearest. In the construction of these the shafts with, a cross section of 6' and 4' generally began to be sunk some thirty or forty feet behind the infantry trench and descended at an easy grade until it reached the water-bearing stratum at the particular point, which was seldom over thirty feet beneath the surface. Then pushing forward, until some sixty to one hundred feet in front of the trench had been gained, the gallery was extended laterally right and left for a greater or less distance to cover the menaced point. This was the general outline of their construction, but some were very elaborately executed, ramifying in every direction. All were ceiled with plank and scantling as the work advanced and were lighted and ventilated by perpendicular shafts. Holes were also bored with earth augurs from the galleries horizontally towards the enemy to serve as acoustic tubes in conveying the sounds of hostile mining. Sentinels were kept in the galleries night and day; and their cool, quiet aisles were delightful retreats from the heat and turmoil of the trenches. It must be confessed, however, that with the ever present death above ground there was something in the dank stillness that reigned within them suggestive of the grave (1910: 282-283).

Confederate engineer, Walter Willis Blackford describes the situation along the Confederate lines defending Petersburg:

Our line extended across spurs of rising ground, and on these hills were the projecting portions of the trenches, called salients, connected together by trenches of lesser strength called curtains. The curtains … were used mainly for passways from one salient to the other and as shelter for the troops. The hot fighting was at the salient, for they commanded the line on each side. It was at these points that the enemy made their closest approaches, their trenches being not more than fifty or sixty yards distant at some of them (1945:262).

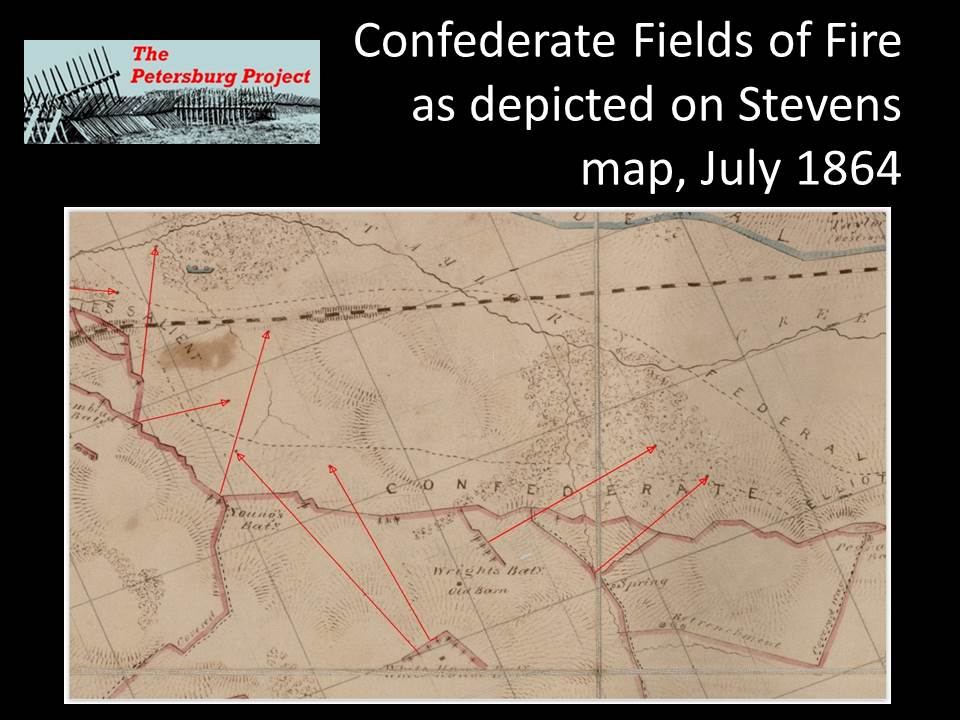

A salient commanded the lines to either side because batteries were situated in them, ready to enfilade enemy troops that ventured into their interlocking fields of fire.

Gracie’s Salient

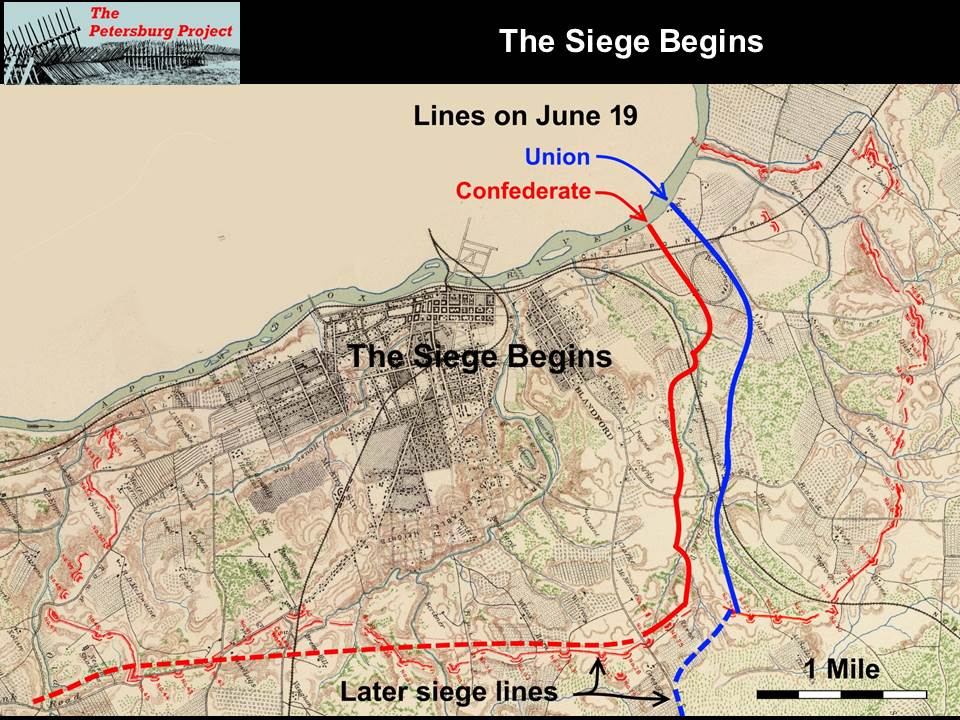

Gracie’s Salient, named after Confederate General Archibald Gracie, was a critical Confederate position located where their lines crossed the Norfolk-Petersburg railroad on the eastern side of the beleaguered town. The Confederate defenses at Gracie’s were not part of the original defenses of the city, called the Dimmock line, which had been overrun by Federal forces on June 15 through the 17th, 1864, when it was skillfully defended by outnumbered forces under General P. G. T. Beauregard. These were new works thrown up during the night of June 17th and fiercely defended on June 18th by Confederate reinforcements now led by Robert E. Lee.

Union elements, under generals Francis Barlow of the II Corps and Robert Potter of the IX Corps had battled to an advanced position within 100 yards of the Confederate line across the obstacle of Poor Creek but under the shelter of rising ground beyond the creek in the Gracie’s Salient vicinity. Both sides used the next month to dig in and strengthen their positions.

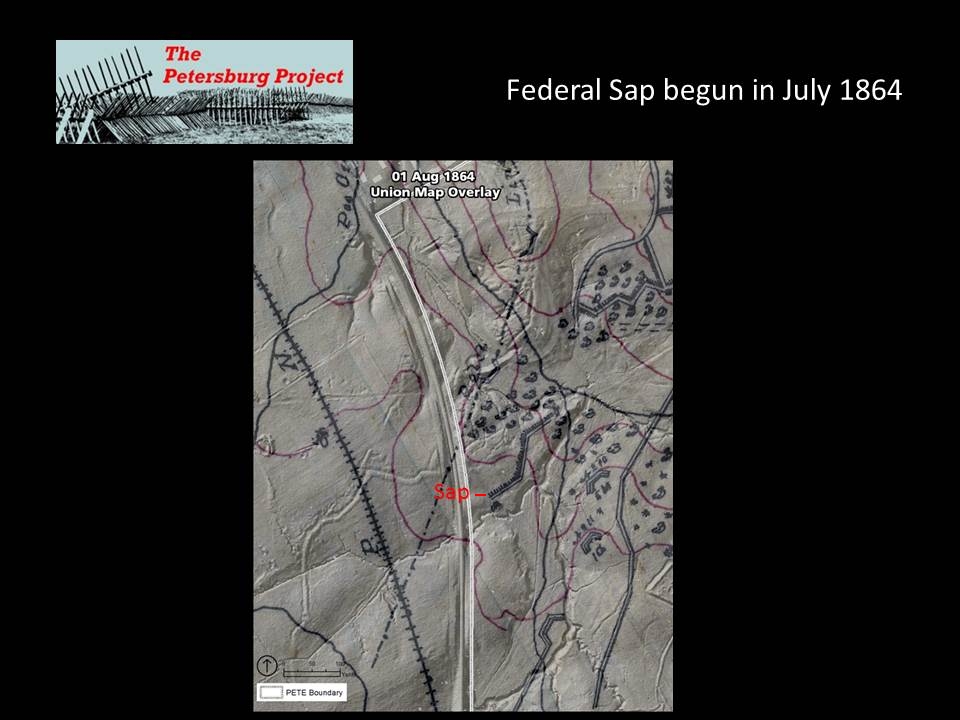

The Federals used classic siege approaches to advance their lines through parallels and sapping in front of Gracie’s Salient. XVIII Corps Engineer Francis Farquahar describes using sapping to create a position for sharpshooters to better reach the Confederate line (OR XLII (I): 680).

To return to 1864, Brigadier General Johnson Hagood, C.S.A., outlines the use of countermines by the Confederate defenders:

Accordingly, counter mines were commenced at the points where the hostile lines were nearest. In the construction of these the shafts with, a cross section of 6' and 4' generally began to be sunk some thirty or forty feet behind the infantry trench and descended at an easy grade until it reached the water-bearing stratum at the particular point, which was seldom over thirty feet beneath the surface. Then pushing forward, until some sixty to one hundred feet in front of the trench had been gained, the gallery was extended laterally right and left for a greater or less distance to cover the menaced point. This was the general outline of their construction, but some were very elaborately executed, ramifying in every direction. All were ceiled with plank and scantling as the work advanced and were lighted and ventilated by perpendicular shafts. Holes were also bored with earth augurs from the galleries horizontally towards the enemy to serve as acoustic tubes in conveying the sounds of hostile mining. Sentinels were kept in the galleries night and day; and their cool, quiet aisles were delightful retreats from the heat and turmoil of the trenches. It must be confessed, however, that with the ever present death above ground there was something in the dank stillness that reigned within them suggestive of the grave (1910: 282-283).

Confederate engineer, Walter Willis Blackford describes the situation along the Confederate lines defending Petersburg:

Our line extended across spurs of rising ground, and on these hills were the projecting portions of the trenches, called salients, connected together by trenches of lesser strength called curtains. The curtains … were used mainly for passways from one salient to the other and as shelter for the troops. The hot fighting was at the salient, for they commanded the line on each side. It was at these points that the enemy made their closest approaches, their trenches being not more than fifty or sixty yards distant at some of them (1945:262).

A salient commanded the lines to either side because batteries were situated in them, ready to enfilade enemy troops that ventured into their interlocking fields of fire.

Gracie’s Salient

Gracie’s Salient, named after Confederate General Archibald Gracie, was a critical Confederate position located where their lines crossed the Norfolk-Petersburg railroad on the eastern side of the beleaguered town. The Confederate defenses at Gracie’s were not part of the original defenses of the city, called the Dimmock line, which had been overrun by Federal forces on June 15 through the 17th, 1864, when it was skillfully defended by outnumbered forces under General P. G. T. Beauregard. These were new works thrown up during the night of June 17th and fiercely defended on June 18th by Confederate reinforcements now led by Robert E. Lee.

Union elements, under generals Francis Barlow of the II Corps and Robert Potter of the IX Corps had battled to an advanced position within 100 yards of the Confederate line across the obstacle of Poor Creek but under the shelter of rising ground beyond the creek in the Gracie’s Salient vicinity. Both sides used the next month to dig in and strengthen their positions.

The Federals used classic siege approaches to advance their lines through parallels and sapping in front of Gracie’s Salient. XVIII Corps Engineer Francis Farquahar describes using sapping to create a position for sharpshooters to better reach the Confederate line (OR XLII (I): 680).

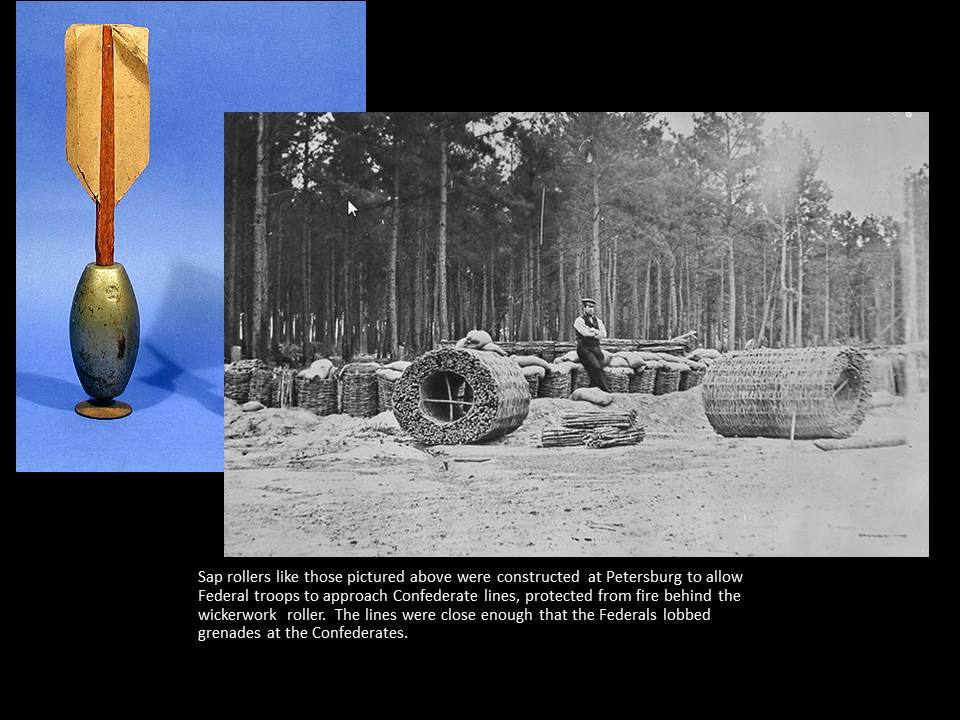

Confederate reports mention two sap rollers operating in front of this salient (OR XLII (II): 1158). Sap-rollers were large wickerwork cylinders, six feet in diameter, filled with tamped earth that protected troops excavating saps from enemy fire. Additional protection was provided by executing sapping work at night and lining the approach trenches with gabions and sandbags.

On July 19th, an officer of the 13th Indiana went to the far end of the sap and tossed twenty hand grenades at the Confederate skirmish pits, which were no more than 20 yards away (Hess 2009:44)

The Confederates were equally comprehensive in their defense of this salient, which was constantly strengthened. Although a large Columbiad siege gun was mounted in a battery behind the lines, other batteries, mapped in mid-July, consisted of smaller guns and mortars, situated to cover the territory between the lines and cover possible enemy approaches.

.

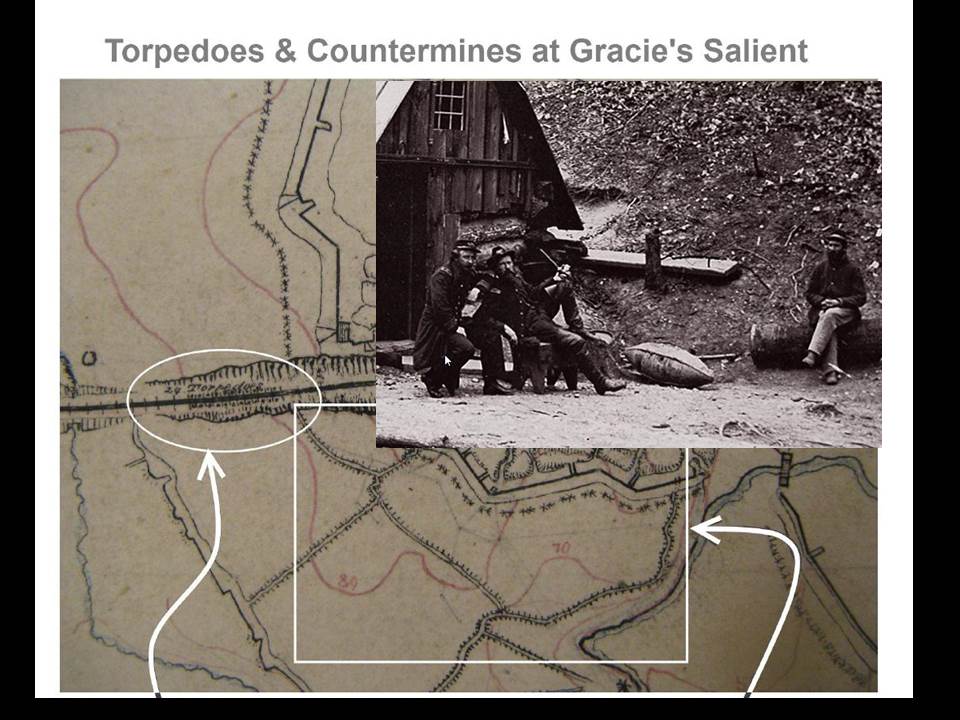

The Confederate map of mid-July also shows cavalier, or secondary works that could overshoot the advanced works, constructed behind particularly vulnerable locations such as Gracie’s and Pegram’s salients. Additionally, the Confederates planted twenty four torpedoes, pressure sensitive explosives of the sort used to blow holes in ship’s hulls, in the Norfolk Railroad cut where it entered their lines to deter this approach.

The Confederate map of mid-July also shows cavalier, or secondary works that could overshoot the advanced works, constructed behind particularly vulnerable locations such as Gracie’s and Pegram’s salients. Additionally, the Confederates planted twenty four torpedoes, pressure sensitive explosives of the sort used to blow holes in ship’s hulls, in the Norfolk Railroad cut where it entered their lines to deter this approach.

he Federal mine resulting in the Crater is frequently referred to as if it were a unique marvel of military engineering. It was indeed unique in overcoming ventilation concerns and other issues to stretch over 500 feet in length. However, at the same time Pennsylvania miners were excavating their tunnel, Confederate engineers were overseeing counter-mining efforts in at least six locations.

Their effort at Gracie’s was unique on the Confederate side in that, on July 31, the day after the battle of the Crater, the Confederates attempted to detonate two explosive chambers at the ends of two tunnel branches in an attempt to destroy Federal saps and drive the Yankees back across Poor Creek. As with the Federal mine the day before, the first attempt at firing the mine didn’t work (OR XLII (II): 1158). The Confederates rethought their approach, dug one gallery closer to the enemy, and on August 5, detonated two charges totaling 850 pounds of powder at two locations on this gallery. The effects were disappointing- General Bushrod Johnson reported that the “effect was slight. Not a gabion or saproller displaced, nor much of a crater formed” (OR XVII(I):885). Beauregard reported the attempt as “experimental” (OR XVII (II): 1163).

A vivid account of the Confederate mine is given in A Record of the Twenty-third Regiment Mass. Vol. Infantry in the War of the Rebellion 1861-1865.

"5 Aug., '64. The date of what is sometimes called, by way of distinction " our mine." The subjoined account

from the New York Herald is a graphic account of the affair in a general way. Sergt. Andrews of "A" adds some

interesting detail and more minute topography.

H. Qr., 18th Corps. In the Field, 6 Aug., '64

"From numerous deserters, that have entered our lines within the last week, it had been discovered that the rebels were mining in several places on onr front. We were, therefore, fully prepared, though somewhat surprised, when at about five o'clock yesterday afternoon, a mine blew up between our line and that of the enemy, the explosion being Immediately succeeded by rapid and successive volleys of musketry. The smoke from the explosion had hardly cleared away, when

our men answered the rebel fire and drowned the rebel yell with their wild cheers of derision, at the failure of their mining operations. The enemy had, in all probability, Intended to blow up a sap we had run out towards their line, and charge through the opening. They had, however, sadly miscalculated the distance. The explosion took place five rods In advance of the head of the sap. Not a particle of the debris was thrown Into any portion of our lines, and the sharpshooters did not even think It necessary to abandon the sap. A mass of dirt, nearly 80 feet in diameter was thrown into the air to the height of nearly 100 feet. The enemy, seeing their mine a failure, satisfied themselves with rising behind their works and pouring in heavy musketry, mostly on Ames's front. The losses on our side were hardly greater than on an ordinary day's picket-firing."

Our second line, at this point, was among trees on the rebel- ward slope of a hill. The intervening valley was

crossed by a zig-zag. The rebels were a few feet beyond the crest of the next hill, and our skirmishers in various

pits and gopher-holes on its acclivity. A small log-house, on the line of our works, was well riddled with all manner of missiles, but, perhaps, added something to the security of two bomb-proofs, so called (holes for shelter from direct fire and offering some protection from the flying bits of shells), near it. Here, for some days before the mine was sprung, the ear applied to the logs in the works, or, better still, to a ramrod thrust into the earth, could detect the sounds of digging. This part of the line, held by a small party representing three companies of the 23rd (and, of these, Co. 'F* by one Corporal), was separated from the rest of the regiment by lower ground, so swampy that it had been left unfortified, and, of course, unoccupied.

The mine was more directly opposite that part of the line held by the rest of the regiment. They were, in fact, running the sap which the rebels tried to blow up. Even here, although the shock of the explosion threw down the gabions upon the men at work in the sap, very little of the material thrown up by the mine fell within our lines (225-226)."

And another account from Bearing Arms in the Twenty-seventh Massachusetts Regiment of Volunteers, by W.P. Derby, 1883:

As an effect of the mine explosion a sense of insecurity sprang up along both lines. At points where our fortifications

ran close to the enemy's, our sharpshooters would joke them about the mine, asking them how they liked to go to heaven that way, and if they were ready to go ; but it was evidently a sore subject for our men too, as they constantly

expected a similar experience. A sap had been run from our lines to within about fifty feet of the rebel fortifications,

and was occupied by portions of the Star Brigade. Our sharpshooters at this close range had so covered the enemy's works as to threaten their capture. This sap was occupied by the Twenty-Third and Twenty-Seventh Mass. Regiments on the 4th and 5th of August. During the 4th suspicious sounds were heard which satisfied us that the enemy were mining close by, awaking not over comfortable sensations. There is no insecurity quite like that of feeling that the ground beneath you is likely to engulf you at any moment. About five o'clock, the morning of the 5th, we were suddenly aroused by an explosion just in front of our works, which buried us in a cloud of debris and smoke, but with no greater injury than

a genuine scare, as the enemy had miscalculated the distance. The explosion was followed by a sortie of the enemy under cover of a sharp artillery fire, but they were hurled back to their intrenchments with heavy loss. The Twenty-Seventh Mass., though in the sharpest of the engagement, were well protected by the intrenchments, and hence escaped unharmed. Col. Steadman, commander of Steadman's Brigade (next to us in line), was killed during this action (pages 363-364).

As far as is known, these underground galleries were never used again in an offensive manner, but they were maintained and patrolled as countermines, particularly in light of serious worries verging on hysteria the Confederate rank and file had about Yankee mining efforts after the massive explosion on July 30th (Blackford:1945).

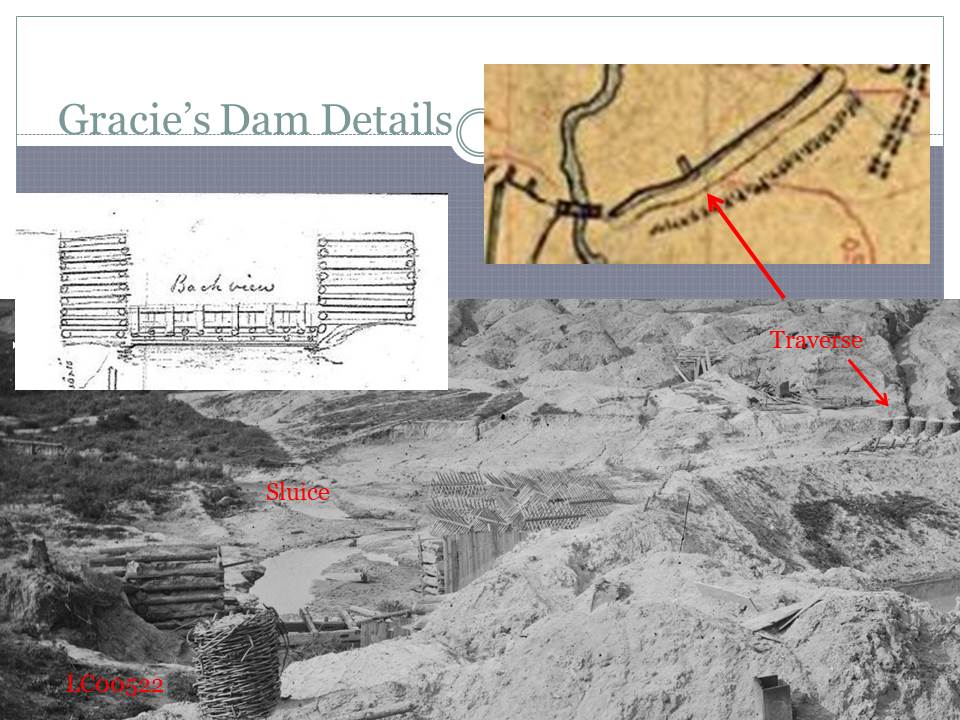

The Confederates finally drove the Federals back to the other side of Poor Creek, through another form of earth manipulation, on November 6, 1864. The Union advanced line awoke to find the Confederates had closed a dam across the creek, raising waters to form a pond, which cut them off from the rest of the Army. These troops were captured and the Federal command decided to abandon the position.

Their effort at Gracie’s was unique on the Confederate side in that, on July 31, the day after the battle of the Crater, the Confederates attempted to detonate two explosive chambers at the ends of two tunnel branches in an attempt to destroy Federal saps and drive the Yankees back across Poor Creek. As with the Federal mine the day before, the first attempt at firing the mine didn’t work (OR XLII (II): 1158). The Confederates rethought their approach, dug one gallery closer to the enemy, and on August 5, detonated two charges totaling 850 pounds of powder at two locations on this gallery. The effects were disappointing- General Bushrod Johnson reported that the “effect was slight. Not a gabion or saproller displaced, nor much of a crater formed” (OR XVII(I):885). Beauregard reported the attempt as “experimental” (OR XVII (II): 1163).

A vivid account of the Confederate mine is given in A Record of the Twenty-third Regiment Mass. Vol. Infantry in the War of the Rebellion 1861-1865.

"5 Aug., '64. The date of what is sometimes called, by way of distinction " our mine." The subjoined account

from the New York Herald is a graphic account of the affair in a general way. Sergt. Andrews of "A" adds some

interesting detail and more minute topography.

H. Qr., 18th Corps. In the Field, 6 Aug., '64

"From numerous deserters, that have entered our lines within the last week, it had been discovered that the rebels were mining in several places on onr front. We were, therefore, fully prepared, though somewhat surprised, when at about five o'clock yesterday afternoon, a mine blew up between our line and that of the enemy, the explosion being Immediately succeeded by rapid and successive volleys of musketry. The smoke from the explosion had hardly cleared away, when

our men answered the rebel fire and drowned the rebel yell with their wild cheers of derision, at the failure of their mining operations. The enemy had, in all probability, Intended to blow up a sap we had run out towards their line, and charge through the opening. They had, however, sadly miscalculated the distance. The explosion took place five rods In advance of the head of the sap. Not a particle of the debris was thrown Into any portion of our lines, and the sharpshooters did not even think It necessary to abandon the sap. A mass of dirt, nearly 80 feet in diameter was thrown into the air to the height of nearly 100 feet. The enemy, seeing their mine a failure, satisfied themselves with rising behind their works and pouring in heavy musketry, mostly on Ames's front. The losses on our side were hardly greater than on an ordinary day's picket-firing."

Our second line, at this point, was among trees on the rebel- ward slope of a hill. The intervening valley was

crossed by a zig-zag. The rebels were a few feet beyond the crest of the next hill, and our skirmishers in various

pits and gopher-holes on its acclivity. A small log-house, on the line of our works, was well riddled with all manner of missiles, but, perhaps, added something to the security of two bomb-proofs, so called (holes for shelter from direct fire and offering some protection from the flying bits of shells), near it. Here, for some days before the mine was sprung, the ear applied to the logs in the works, or, better still, to a ramrod thrust into the earth, could detect the sounds of digging. This part of the line, held by a small party representing three companies of the 23rd (and, of these, Co. 'F* by one Corporal), was separated from the rest of the regiment by lower ground, so swampy that it had been left unfortified, and, of course, unoccupied.

The mine was more directly opposite that part of the line held by the rest of the regiment. They were, in fact, running the sap which the rebels tried to blow up. Even here, although the shock of the explosion threw down the gabions upon the men at work in the sap, very little of the material thrown up by the mine fell within our lines (225-226)."

And another account from Bearing Arms in the Twenty-seventh Massachusetts Regiment of Volunteers, by W.P. Derby, 1883:

As an effect of the mine explosion a sense of insecurity sprang up along both lines. At points where our fortifications

ran close to the enemy's, our sharpshooters would joke them about the mine, asking them how they liked to go to heaven that way, and if they were ready to go ; but it was evidently a sore subject for our men too, as they constantly

expected a similar experience. A sap had been run from our lines to within about fifty feet of the rebel fortifications,

and was occupied by portions of the Star Brigade. Our sharpshooters at this close range had so covered the enemy's works as to threaten their capture. This sap was occupied by the Twenty-Third and Twenty-Seventh Mass. Regiments on the 4th and 5th of August. During the 4th suspicious sounds were heard which satisfied us that the enemy were mining close by, awaking not over comfortable sensations. There is no insecurity quite like that of feeling that the ground beneath you is likely to engulf you at any moment. About five o'clock, the morning of the 5th, we were suddenly aroused by an explosion just in front of our works, which buried us in a cloud of debris and smoke, but with no greater injury than

a genuine scare, as the enemy had miscalculated the distance. The explosion was followed by a sortie of the enemy under cover of a sharp artillery fire, but they were hurled back to their intrenchments with heavy loss. The Twenty-Seventh Mass., though in the sharpest of the engagement, were well protected by the intrenchments, and hence escaped unharmed. Col. Steadman, commander of Steadman's Brigade (next to us in line), was killed during this action (pages 363-364).

As far as is known, these underground galleries were never used again in an offensive manner, but they were maintained and patrolled as countermines, particularly in light of serious worries verging on hysteria the Confederate rank and file had about Yankee mining efforts after the massive explosion on July 30th (Blackford:1945).

The Confederates finally drove the Federals back to the other side of Poor Creek, through another form of earth manipulation, on November 6, 1864. The Union advanced line awoke to find the Confederates had closed a dam across the creek, raising waters to form a pond, which cut them off from the rest of the Army. These troops were captured and the Federal command decided to abandon the position.

So, where were the underground tunnels at Gracie’s salient? By the end of the war, when it was mapped and photographed by Federal topographic engineers, this sector of the Confederate lines was a jumbled warren of trenches, parapets and bombproof shelters.

So, where were the underground tunnels at Gracie’s salient? By the end of the war, when it was mapped and photographed by Federal topographic engineers, this sector of the Confederate lines was a jumbled warren of trenches, parapets and bombproof shelters.

One hundred and fifty years later, these have eroded into a confusing welter of earthen humps, covered with dense trees. The Norfolk Railroad, Poor Creek and the still extant Confederate dam provide some landmarks, but, on the ground, it is difficult to make sense of surface structures much less those hidden underground.

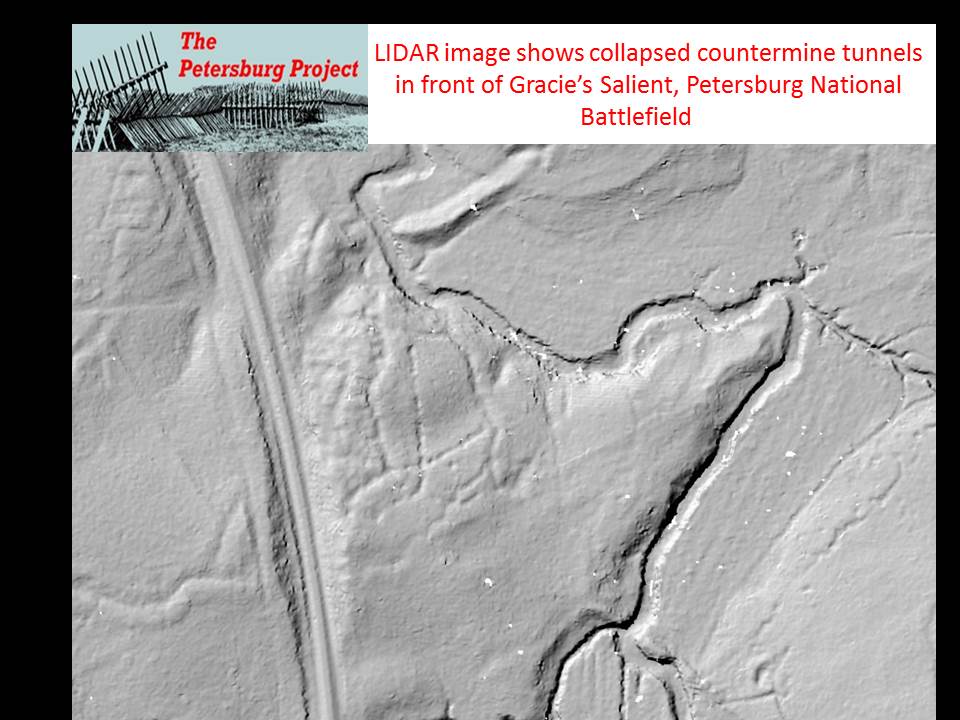

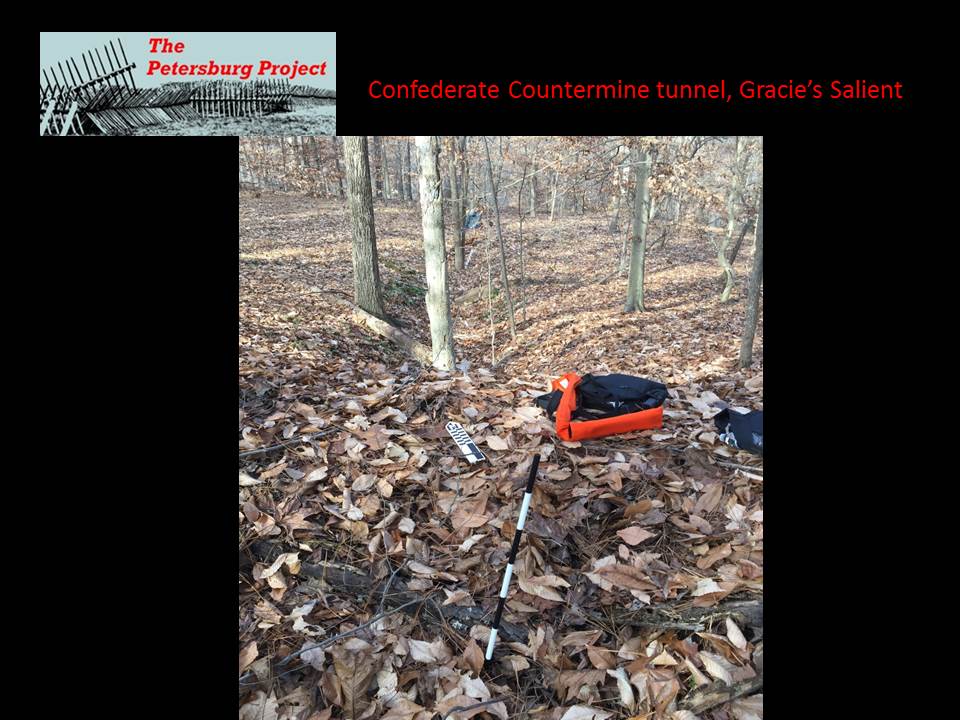

Our breakthrough was acquisition of LIDAR imagery, compliments of the U.S. Army installation at Fort Lee.

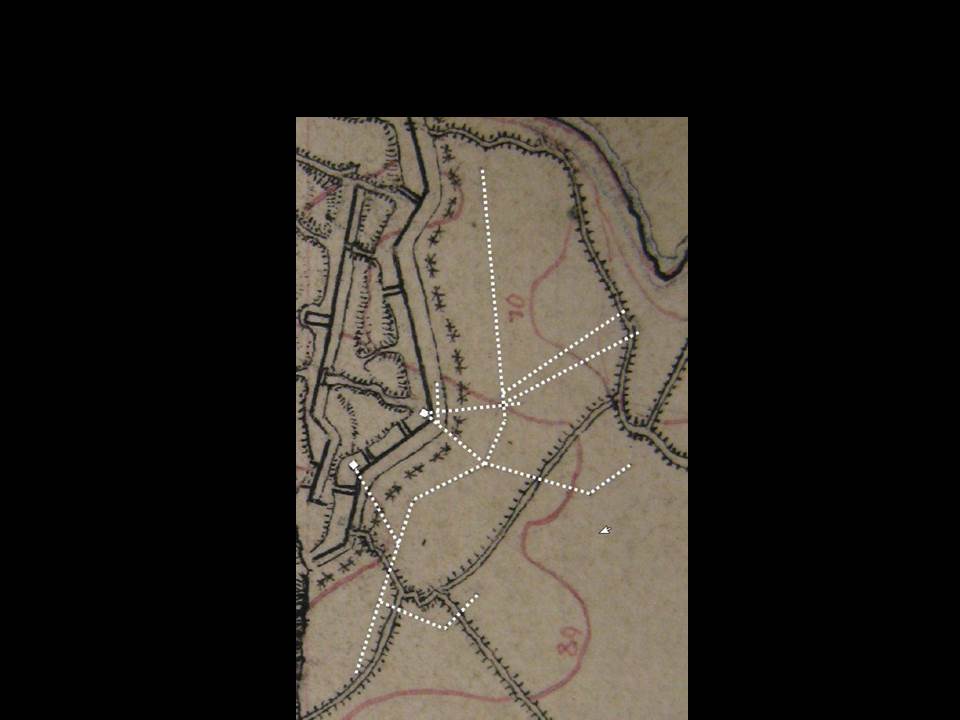

My colleagues and co-authors, David Lowe and Phil Shiman made a cognitive leap, comparing LIDAR with a detailed Union engineer map done immediately after the fall of Petersburg that we call the “Manuscript Michler” (Library of Congress cw0607200).

On this map, faint pencil lines were drawn in front of some of the Confederate positions, roughly paralleling them. These had been a mystery. We had noted them, but thought they were rough outlines of the final inked lines. Other lines may have run back under the earthworks, but it was difficult to distinguish these marks from other penciled in grid marks or triangulation lines. Dave and Phil thought they might be the lost Gracie’s underground tunnels and field examination and GIS overlays verified they were the partially collapsed remnants of the galleries which probably collapsed between the underground framing.

Wright’s Battery Countermines

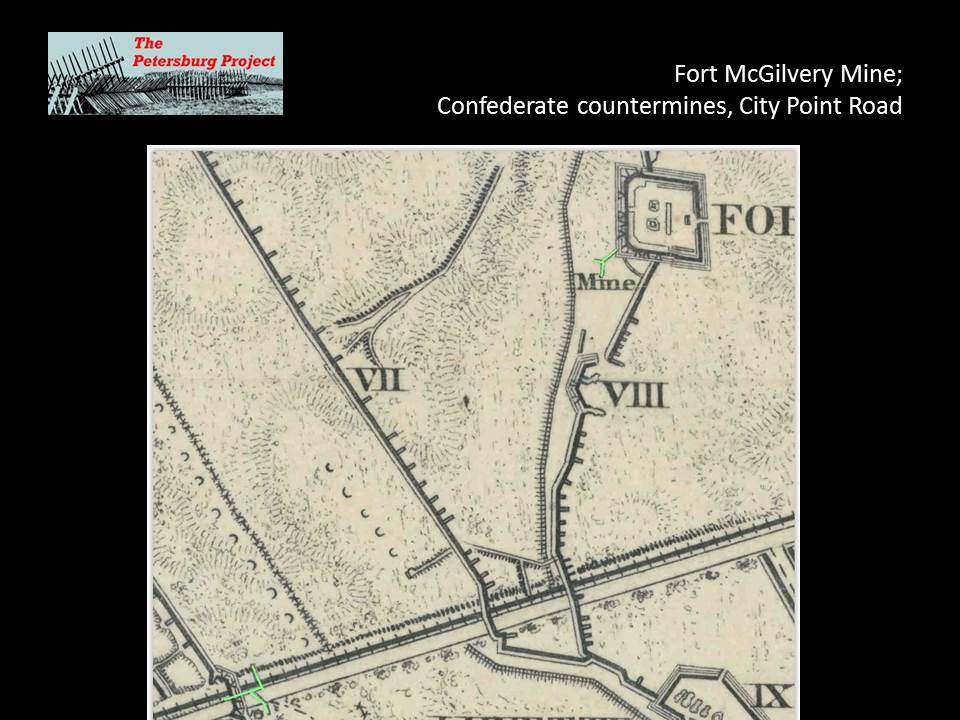

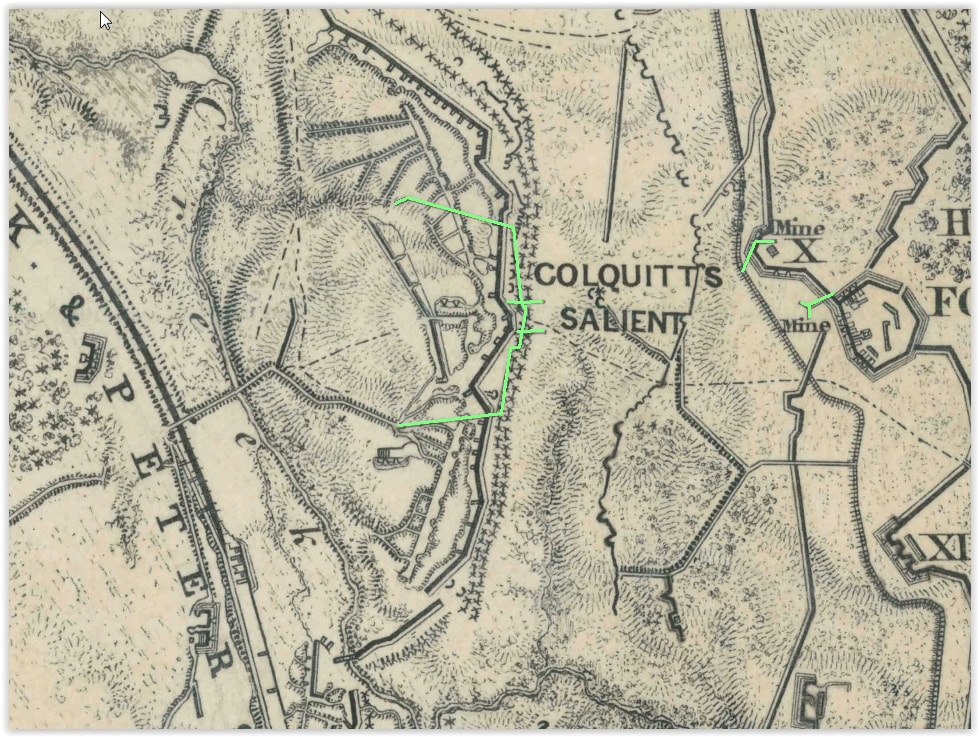

We soon recognized that the draft Michler showed possible galleries in front of another Confederate salient on a raised spur of ground with dead ground in front of it at Wright’s battery.

This Confederate battery play a major role in the Confederate victory at the Battle of the Crater in that it enfiladed the Union advance and was hidden from their artillery by a screen of trees. Nonetheless, it was vulnerable to Union mining from the base of the hill, within those trees. A LIDAR overlay [slide] indicated the location where the gallery out through the Confederate lines made a T intersection with the gallery in front of the line had caved in. A summer field expedition where we battled legions of ticks verified this hypothesis.

This Confederate battery play a major role in the Confederate victory at the Battle of the Crater in that it enfiladed the Union advance and was hidden from their artillery by a screen of trees. Nonetheless, it was vulnerable to Union mining from the base of the hill, within those trees. A LIDAR overlay [slide] indicated the location where the gallery out through the Confederate lines made a T intersection with the gallery in front of the line had caved in. A summer field expedition where we battled legions of ticks verified this hypothesis.

This set of galleries may have been deeper or better braced, because most of it shows no surface evidence of collapse, if the 1865 maps are correct. We did find a soil stain of one of the cross braces.

We eventually realized that the Confederate tunnels were illustrated on the final, published, inked versions of the Federal post war maps-many were drawn in the same style as minor surface communications trenches and that is what they were assumed to be for the last century and a half--minor trenches that no longer existed. Federal mines, however, were clearly marked as mines on this map and drawn in a different style. A few sets of Confederate underground mines were drawn the same way, but not labelled as mines. There are yet other lost underground features along the Petersburg front that may still exist under modern routes 36 and 460.

Now that we understand the maps more clearly, it can be seen that there are more extensive countermine galleries under the Crater/Pegram’s battery portion of the Confederate line within Petersburg National Battlefield that have not yet caved in. These were excavated after the battle--in fact, dug through a nausea inducing horizon of decomposing bodies that caused engineer Blackford to requisition ventilation fans from Richmond to siphon off the stench. Ground penetrating radar work done in the vicinity of the Crater by Bruce Bevan (n.d.) to try and establish its original outlines, ran into a confusing array of data that needs to be re-interpreted now that we know where countermining occurred along this part of the front.

At all of these locations, additional ground penetrating radar analysis can help establish the full extent of the tunneling in terms of the length, width, depth and the intactness of the galleries and what might be left in them to counter enemy breakthroughs above or below ground. Minimally invasive introduction of cameras or LIDAR into the tunnels can record these remains of what Confederate engineer Blackford called “a strange sort of warfare underground” (1945:262) before they are further lost to the ravages of time.

References

Bevan, Bruce

n.d. Geophysical Exploration of the Crater, Petersburg National Battlefield. Prepared for the National Park Service.

Blackford, W. W.

1945 War Years with Jeb Stuart. Charles Scribner& Sons: New York.

Blades, Brooke

2001 Archeological Overview and Assessment, Main Unit, Petersburg National Battlefield. National Park Service.

Emmerton, James A.

1886 AA Record of the Twenty-third Regiment Mass. Vol. Infantry in the War of the Rebellion 1861-1865. https://archive.org/stream/arecordtwentyth00unkngoog/arecordtwentyth00unkngoog_djvu.txtRecord of

the Twenty-third

Hess, Earl J.

2009 In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications and Confederate Defeat. University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill.

Hagood, Johnson

1910 Memoirs of the War of Secession, From the Original Manuscripts of JOHNSON HAGOOD, Brigadier-General,

C. S. A., The State Company; Columbia, SC.

Jackson, Harry L.

1998 First Regiment Engineer Troops, P. A. C.S.: Robert E. Lee’s Combat Engineers. R.A. E. Design and Publishing: Louisa, VA.

1880-1901 The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC.

Colquitt's Countermine

updated 04/09/2018