This paper was presented at the 2018 Society of Historical Archaeology Conference in New Orleans.

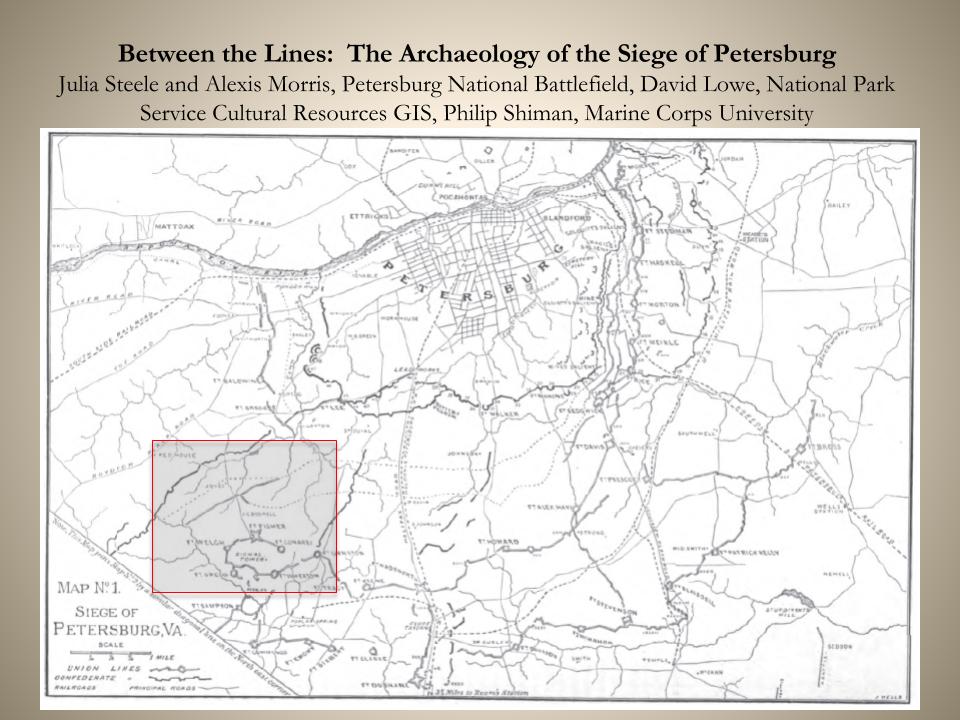

By the time the important Confederate transportation center of Petersburg fell after a nine and a half month siege, the combatants faced each other in two lines of complex earthworks surrounding the beleaguered city in a more than 35 mile long arc. Impressive as these major works were, the territory between the entrenched lines contains a fertile archeological record that attests to the skill and tenacity of both sides. The U. S. failed in its initial attempt to take the city by surprise but ultimately triumphed by keeping up relentless pressure on the Confederate defenders and extending the lines to the west, in the process picking off dwindling Confederate supply links. The cornered Confederates were not an easy target and the Federals had to remain alert and defensive against C.S.A. counter-moves and the Confederacy’s skillful yet desperate efforts to defend both Petersburg and, by proxy, their capital at Richmond, twenty-five miles to the north.

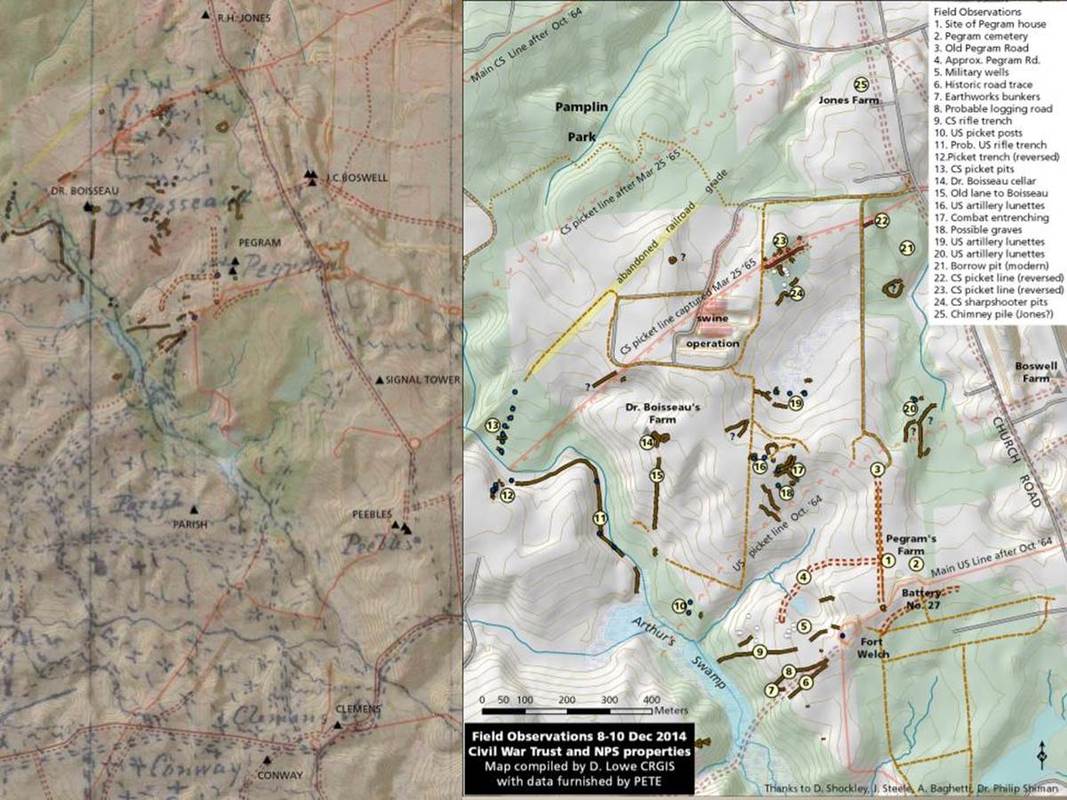

The big historical picture is well known, as are the general outlines of the major battles that punctuated the siege: what has not been well explored by traditional historians is the non-textual data that is the purview of archeology. This paper focuses on the physical record of the Petersburg campaign in the final year of the American Civil War as it relates to the “no man’s land” between the major lines of fortifications. We explore picket lines and posts, saps, covered ways, tunnels, sharpshooter posts, fields of fire and organized observation from signal stations as the sides try to sense advantageous moves and countermoves. Placement of observation points and use of cover shift as the combatants confront different obstacles and terrain features and react to the enemy’s attempts to manage the same challenges. We use every tool in the modern arsenal to analyze the territory between the lines- map and photographic analysis, LIDAR, GPS and excavation- and find the associated archeological record. In our case, excavation is the least used methodology for knowing the field, partly because ground disturbing activities, including scientific excavation, destroys the resource, but also because there are other means of knowing the resource.

No man’s land is a term that was used in English at least as far back as the Domesday Book in the eleventh century to describe territory outside the bounds of control by a lawful authority. By World War I it applied to the area of land between two enemy trench systems, which neither side wished to cross or seize due to fear of being repelled by the enemy in the process. Such territory was hardly lifeless or serene- both sides used every means at hand to cover the disputed territory with infantry and artillery fields of fire, set up obstacles and provide warning of attacks.

The big historical picture is well known, as are the general outlines of the major battles that punctuated the siege: what has not been well explored by traditional historians is the non-textual data that is the purview of archeology. This paper focuses on the physical record of the Petersburg campaign in the final year of the American Civil War as it relates to the “no man’s land” between the major lines of fortifications. We explore picket lines and posts, saps, covered ways, tunnels, sharpshooter posts, fields of fire and organized observation from signal stations as the sides try to sense advantageous moves and countermoves. Placement of observation points and use of cover shift as the combatants confront different obstacles and terrain features and react to the enemy’s attempts to manage the same challenges. We use every tool in the modern arsenal to analyze the territory between the lines- map and photographic analysis, LIDAR, GPS and excavation- and find the associated archeological record. In our case, excavation is the least used methodology for knowing the field, partly because ground disturbing activities, including scientific excavation, destroys the resource, but also because there are other means of knowing the resource.

No man’s land is a term that was used in English at least as far back as the Domesday Book in the eleventh century to describe territory outside the bounds of control by a lawful authority. By World War I it applied to the area of land between two enemy trench systems, which neither side wished to cross or seize due to fear of being repelled by the enemy in the process. Such territory was hardly lifeless or serene- both sides used every means at hand to cover the disputed territory with infantry and artillery fields of fire, set up obstacles and provide warning of attacks.

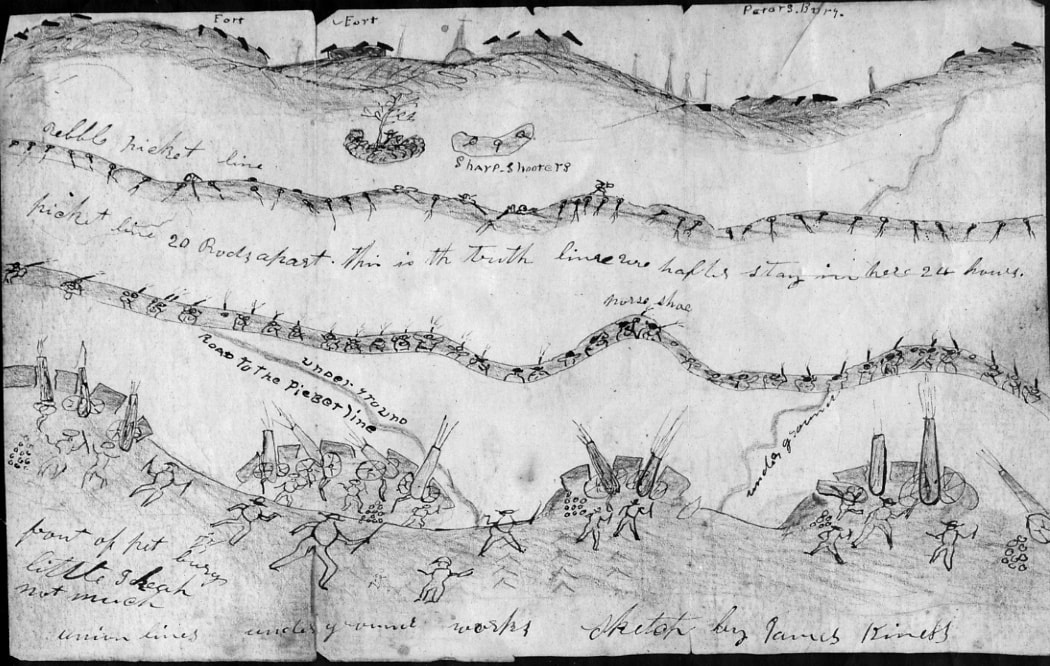

A drawing of the lines at Petersburg (below), from the perspective of Native American soldier, James Kiness, of the 36th Wisconsin infantry provides a vivid glimpse of what the lines looked like to an enlisted man. Bristling guns make clear that to venture between the lines required what Kiness labelled “underground roads”, or covered ways, that lead to the picket line, an advanced line that served as an early warning system against enemy attacks.

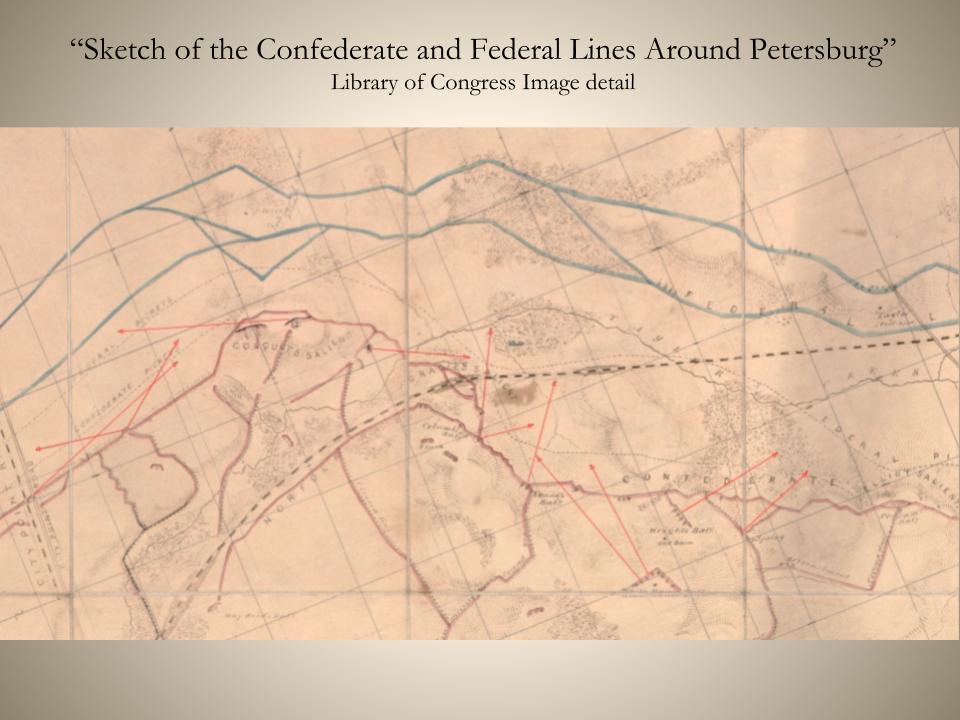

The following map shows the same general area portrayed in the Kiness drawing in the first slide was prepared by Confederate engineers in mid-July, 1864, in an attempt to create a big picture view of this front. Artillery batteries were placed to command specific sectors of the opponent's lines, to oppose and silence the enemy's batteries, or to sweep areas where the enemy might advance. Individual guns were fixed with the range and direction of particular locations within their purview. This detail from the ca. July 13, 1864, Confederate map contains lightly inked gun trajectories, outlined here with red arrows. The trajectories depicted, document guns and mortars specifically placed to command the ground between the lines. The fields of fire of other guns and mortars depicted on the map are not specified, but are probably aimed at Federal batteries in order to counter enemy fire. Stevens Map

LC cw0610000. Stevens Map, July 1864

LC cw0610000. Stevens Map, July 1864

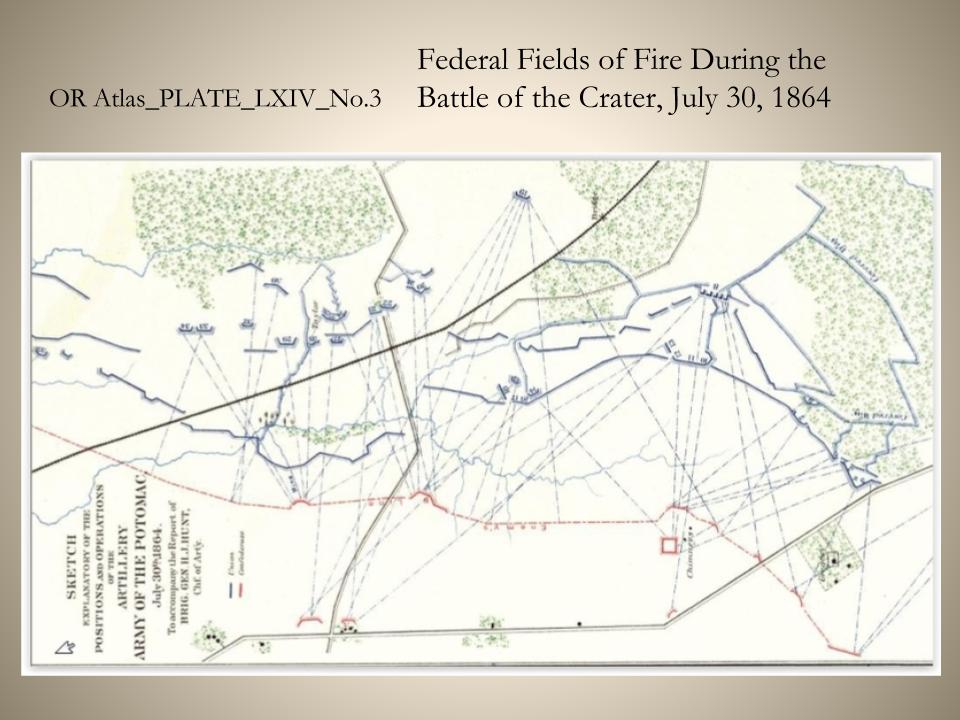

The following map shows U.S. artillery placement during the July, 1864, Battle of the Crater, and reflects the Federal guns used to suppress Confederate artillery firing on the Federal advance, something at which they were only partially successful. Systematic archeological survey has not, in all cases, ground-truthed the Civil War maps, but there really isn’t much reason to doubt that artillery was used in these locations and in this fashion-- although a contract firm preparing a National Register nomination refused to list fields of fire as a contributing resource without such verification. A recent illegal relic hunting case did illustrate that shrapnel from exploded shells littered the ground between the lines on a section of this front and the few minor surveys done for small NPS projects also add to the evidence. It would appear that No-Man’s Land is littered with the debris of battle.

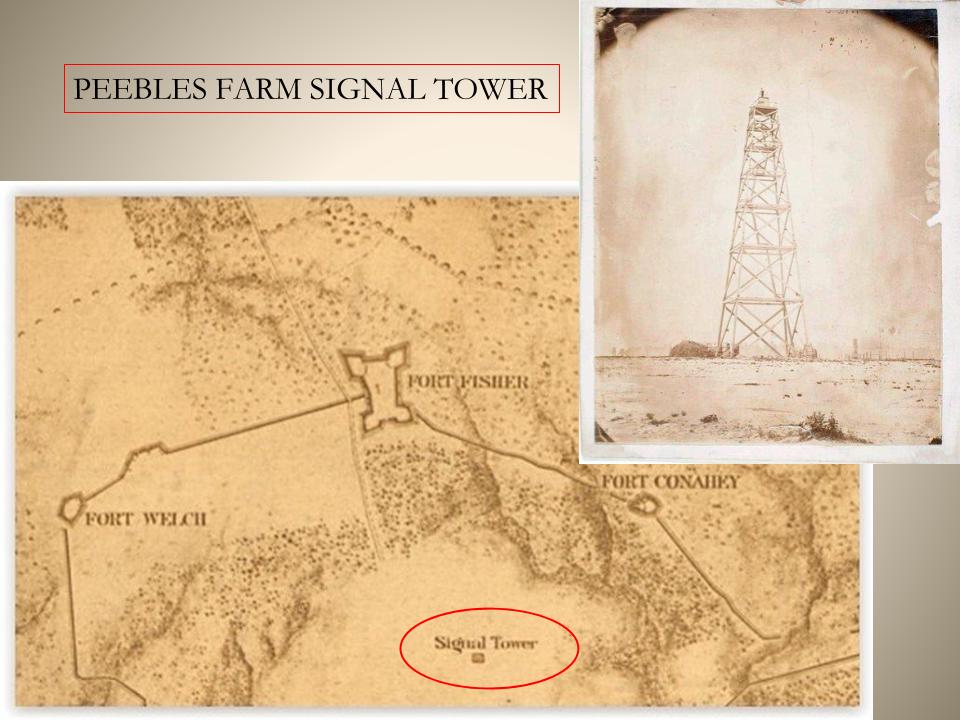

Historical archaeology benefited from the aerial view provided by LIDAR- we also benefit from the Civil War’s closest approach to the bird’s eye view provided by LIDAR and aerial photography. Signal trees, towers and buildings remained vital tools for each army to observe the movements of the enemy behind its lines and catch any advance between the lines from an elevated vantage point. Information gained from such observations could then be relayed through all available means of communication, including signaling by flag or torch. Military uses of these locations included artillery spotting, mapping, and photography. The fourth estate also climbed these posts as special artists drew the siege lines and battlefields and reported war news. The Federal signal tower behind Fort Fisher on the western end of the Union lines is an excellent example of how signal stations were used in multiple ways.

NARA, RG 77, Michler 1867; Chrysler Museum of Art photograph.

NARA, RG 77, Michler 1867; Chrysler Museum of Art photograph.

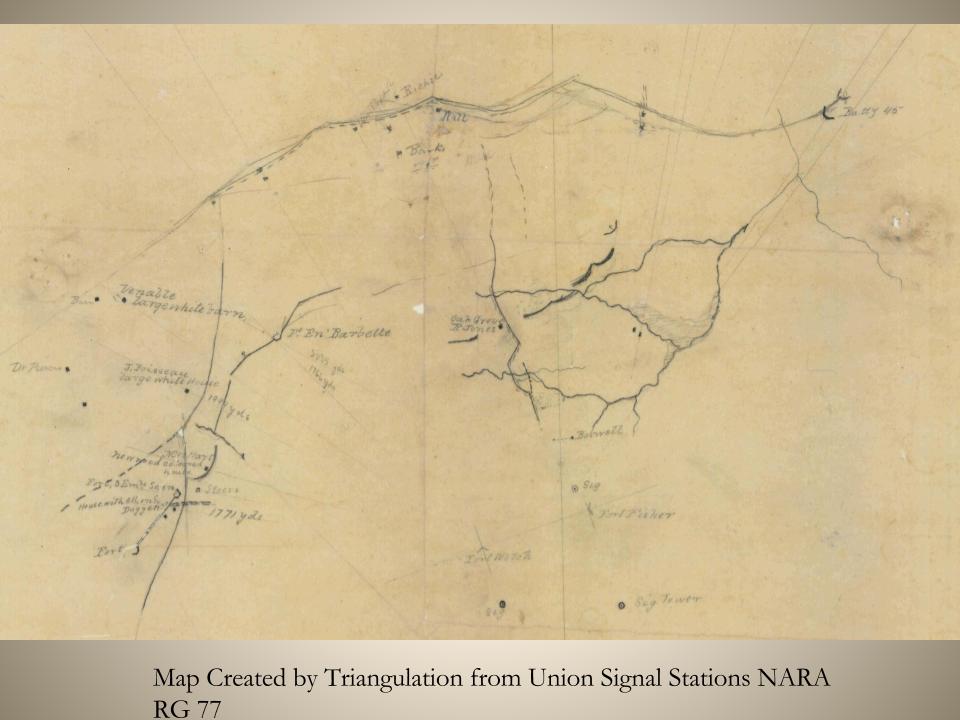

The sketch map below, drawn by topographic engineers, illustrates how Federal mappers used the signal tower and signal trees located on the parapets of Fort Welch and Fort Fisher to triangulate the locations of the Confederate lines from a safe distance during the campaign. We have the benefit of beautiful postwar maps done by the U.S. Topographic engineers, but the preliminary maps drawn during hostilities were of vital importance for planning advances or responding to enemy actions. Both during and after action maps are important to us today, because features on the battlefields and siege lines evolved.

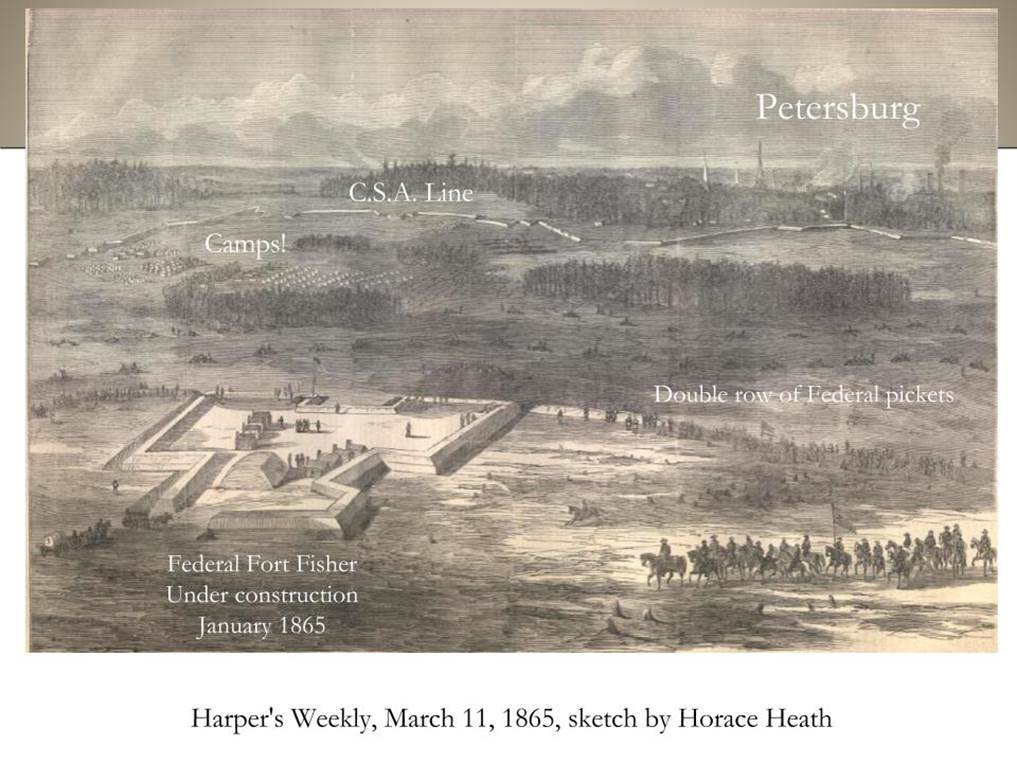

The view was spectacular from a signal tower. The newspaper illustration below shows Fort Fisher, before the southern two bastions were constructed, and the U.S. and Confederate picket lines beyond, with the Confederate line and the city beyond that. Movement on the Boydton Plank Road, major supply artery, and the South Side Railroad could also be observed from the tower. This woodcut also poses a question -- were Confederate troops truly camping and drilling between the lines, hidden from artillery fire by a screen of trees? It certainly looks that way and awaits further scrutiny at a finer grain of resolution -- probably requiring archeological prospecting.

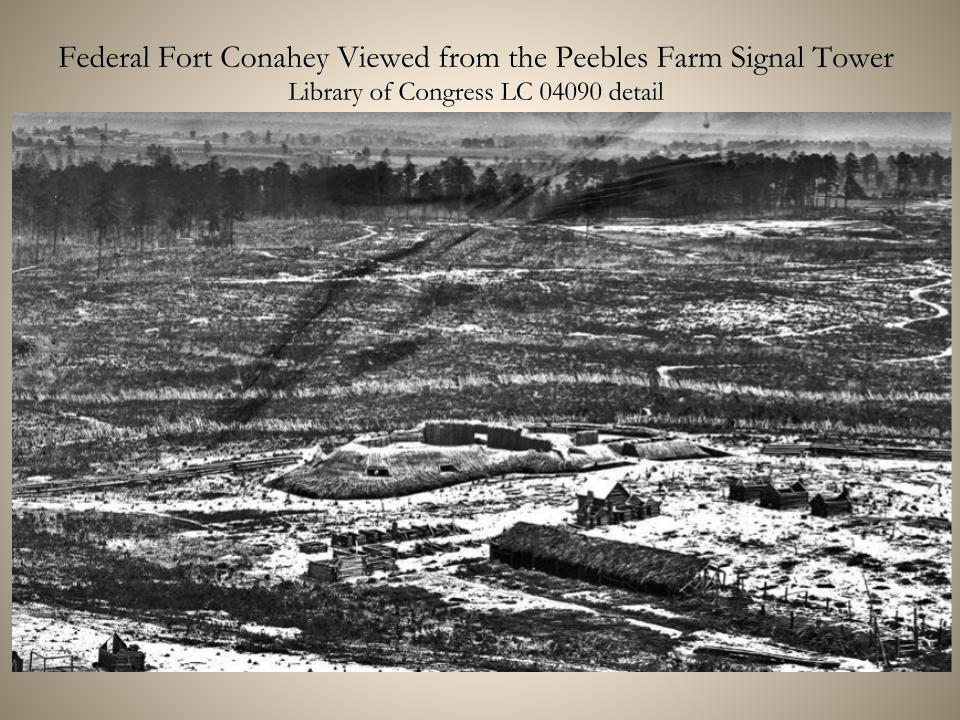

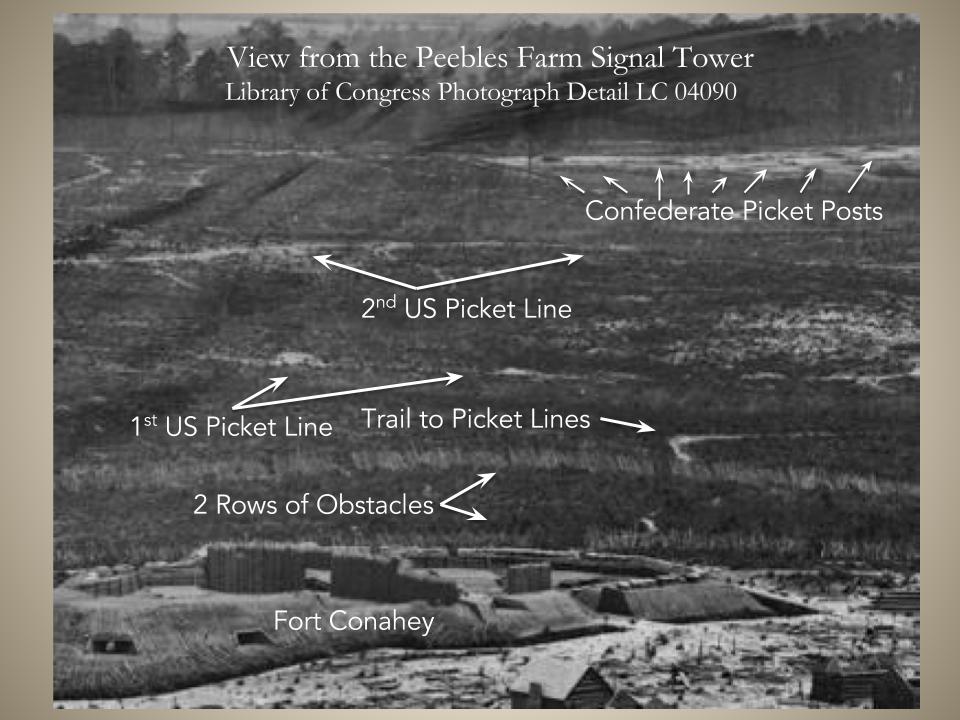

Here is a photograph taken from the top of the same signal tower.

Imagine the daunting task of hauling a Civil War-era camera and glass negative(s) on narrow ladders to the top of a 140-foot signal tower! The result, however, was a breathtaking view of Fort Conahey (center), showing its lethal architecture, including a log stockade that divided the fort into two parts. In the foreground are the remains of deserted winter huts and a stable. Many of the building’s canvas roofs were removed when the armies “upped stakes” on April 3rd, 1865, and marched toward the climax of Appomattox. The photograph looks northeast toward the main Confederate line hidden in the woods in the far distance and provides crisp details of what went on in the territory between the lines.

This photograph shows fine details of the contested territory--two layers of abatis (a hedge constructed of sharpened tree branches) in front of the fort, two Union picket lines, consisting of strong points connected with shallow trenches, and individual Confederate picket posts in the distance that housed 3- and 4-man firing teams. By this time of the war, much of the fighting was done by humble skirmishers on and between the picket lines. Gone were the days of open-field shoulder-to-shoulder assaulting with battle flags flying.

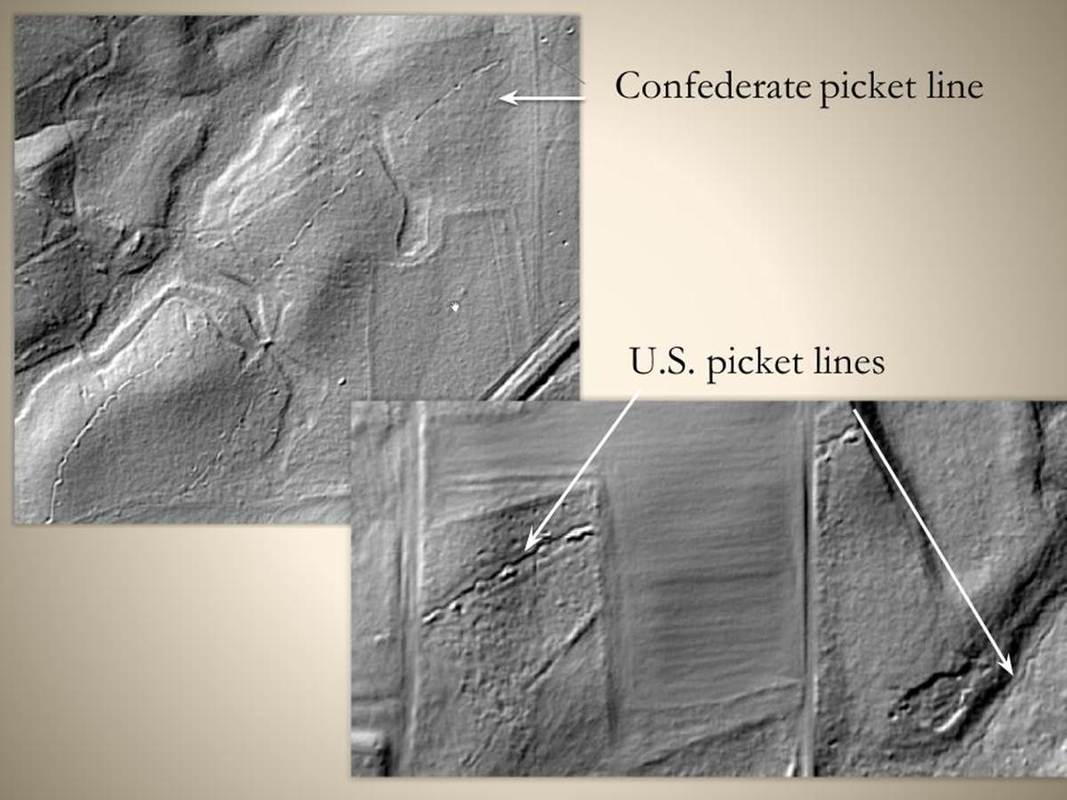

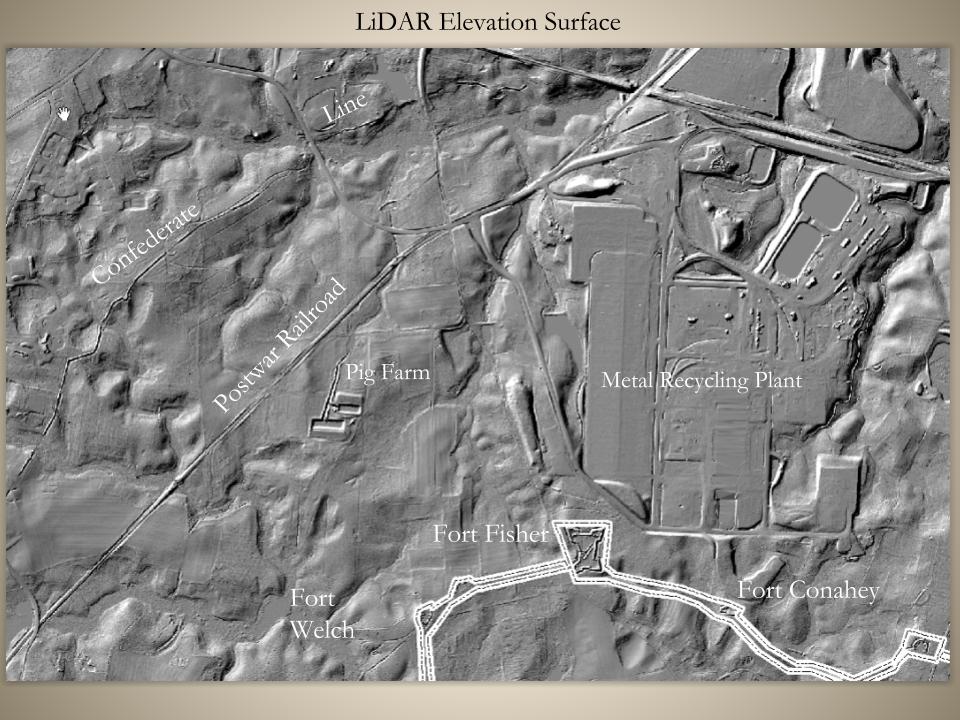

Thanks to FEMA post-Hurricane Sandy coverage flown by state and federal governments, we’ve been able to have the all-seeing eye of LiDAR coverage of this portion of the field. LiDAR has been a godsend in many ways, especially in areas that were once covered by trees- making it difficult for the topographical engineers to accurately map during the war or even post war, or for us to understand the full picture, even today with GPS technology that doesn’t rely on on-the-ground line of sight.

Petersburg Project

Petersburg Project

Having a bird's-eye view allows us to gain a broader understanding of the battlefield. The U.S. military engineers often included picket lines in their maps, but the representation was schematic. LiDAR coverage has given a more accurate picture of these lines, and allows more accurate extrapolation of their location when they have been obliterated in places by post war disturbances. Confederate and Union picket lines show up quite clearly on these LiDAR images from near Fort Welch and Peebles Farm.

The slide below show compares a wartime drawing of the view from U.S. Fort Welch with the view today. The larger terrain features have not been altered to any great extent. The vegetation cover is only slightly different--in fact, the line of trees to the right has protected picket line features from later farming disturbances. The Dr. Boisseau house shown in the sketch survives as a cellar hole and chimney pile.

Top LC 22822; Bottom Petersburg Project

Top LC 22822; Bottom Petersburg Project

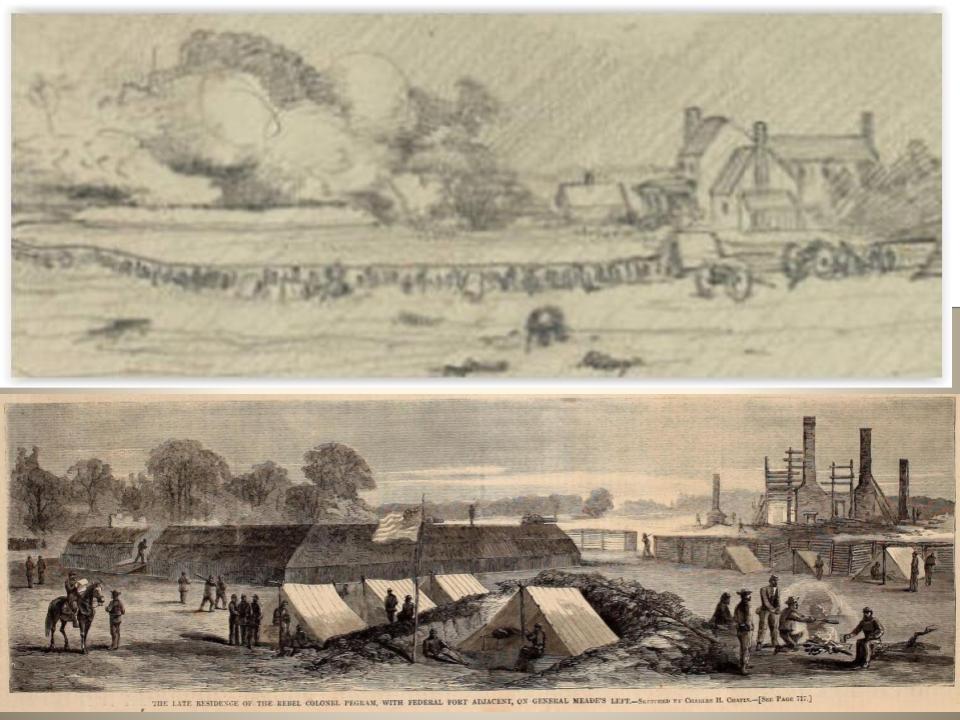

We’ve also discussed the fate of the structures caught in the crossfire and how they are both battlefield landmarks and war materiel. In this location, the Pegram farmhouse and outbuildings were quickly demolished after federal troops gained the ground and Fort Welch was constructed. Because of agricultural activities, there are no surface indications of the Pegram buildings today- their exact location awaits classic archeological investigation. A second house on the battlefield – Dr. Boisseau’s – was also destroyed but it left an obvious cellar hole to mark its existence.

Top, detail of "Fight of Oct. 2d, 1864," artist unknown, in collection of art sent to Frank Leslie's Illustrated newspaper at the New York Historical Society. The sketch was not published. Inscribed at lower left: "Fight of October 2d./troops occupying the rebel lines about mid." Bottom: Sketch by Charles H. Chapin, woodcut published in Harper's Weekly, November 5, 1864.

What the engineers did not map were the myriad of earthworks we call “combat trenching”--hastily constructed earthworks that were ubiquitous by the final year of the war. Hardened troops would dig in for cover whenever an advance toward the enemy paused. These works were not engineered in the sense that the major opposing lines, or even picket lines, were and the mappers ignored them unless they became part of the larger network of fortifications. There are signs of this sort of entrenching on the sector of the lines discussed here- from both the initial U.S. advance west of Petersburg at the end of September-early October, 1864, the picket line assault on March 25, 1865, and the final breakthrough on April 2nd. We’ve discussed this sort of trenching in an earlier paper and elsewhere on our website.

As was the case with armies in the field, all the remote observation in the word does not negate getting one's boots dirty. In order to weave together these disparate threads of information from different times during the campaign into a coherent story, field survey is necessary. We gain much greater insight by toggling between different degrees of resolution and scale as we try to make sense of complex events of the past and their material records.

So, how do we use our various ways of knowing to understand the territory between the lines as we see it today? The VI Corps assault of Confederate lines that led to the fall of Petersburg on April 2, 1865, was launched from Fort Welch. Of critical importance to this successful action was the capture of the Confederate picket line in this sector a week earlier, leaving the Confederate line vulnerable to an approach by the enemy. Parts of the original battlefield terrain have been lost over the years to industry and agriculture. But by combining documentary descriptions, maps, drawings, photographs, and LiDAR surface models, we can compile a better understanding of how the soldiers viewed and used the terrain of battle. Systematic archaeological survey using all the mapping tools available provides useful information on a large scale. Excavation can help in pinpointing the location of the Pegram house or in determining whether a series of depressions we found in the ground were for tents or for burials- smaller scale issues. In the coming year, we will be bringing ground-penetrating radar to bear in areas where we suspect the soldiers were tunneling. As we have tried to show today, these various sources are rich in information, and each provides a different but important piece of the Petersburg mosaic.