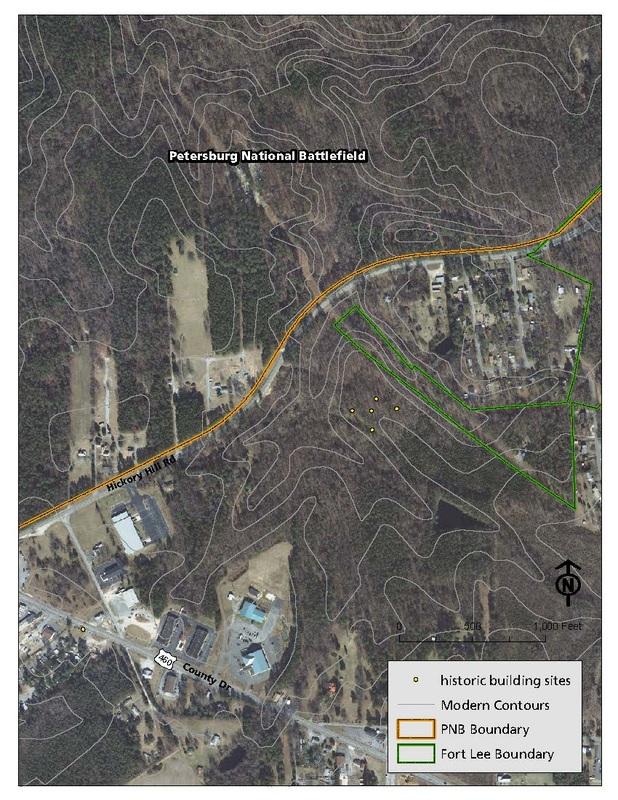

William Shands House "Hickory Hill"

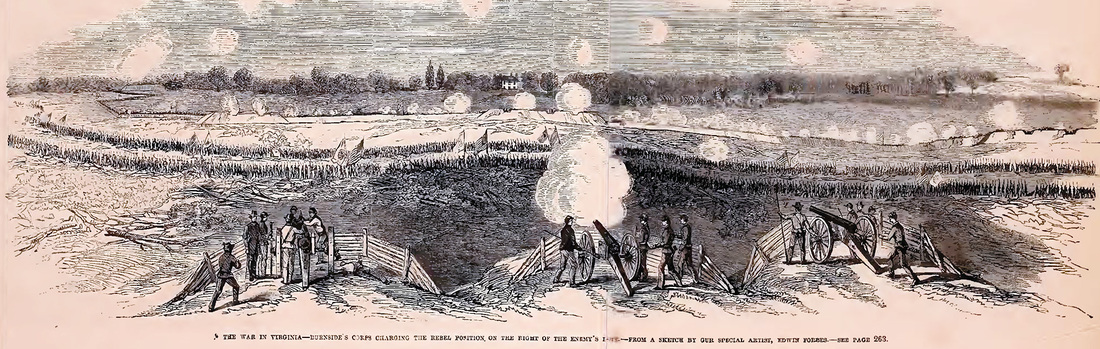

9th Corps Assault at the Shand House against Dimmock Batteries 14 and 15 -- June 16-17, 1864

Shind or Shand? It's "Shands" like your "hands."

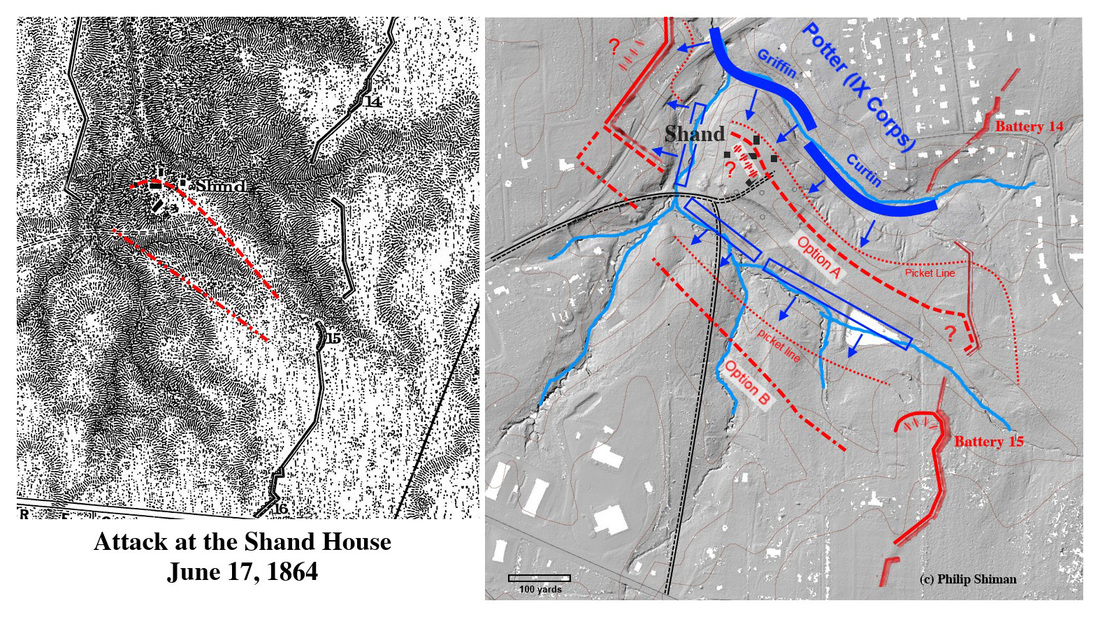

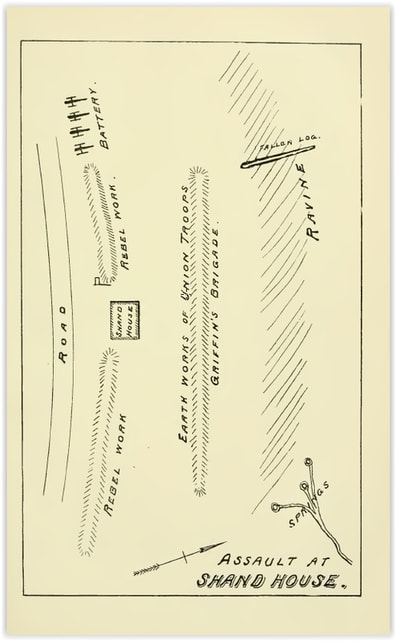

"At the first dawn of day in the morning of the 17th, the division of General Potter (Ninth Corps) carried, in the most gallant manner, the redans and lines on the ridge where the Shind or Shand house stood, capturing four guns, five colors, 600 prisoners, and 1,500 stands of small arms. The troops, Griffin's and Curtin's brigades of Potter's division, were formed in two lines in a deep ravine with precipitous slopes, close up to the works they were to attack. They were ordered not to fire a shot, but to depend on the bayonet. The command, Forward, was passed along the lines in whispers, and the lines, without firing a shot, at once swept over the enemy's works, taking them completely by surprise, and carrying everything before them. The Confederate troops were asleep, with their arms in their hands." -- A. A. Humphreys, The Virginia Campaign

Dawn Attack at the Shand House. Organization and Tactics, Arthur L. Wagner, 1897

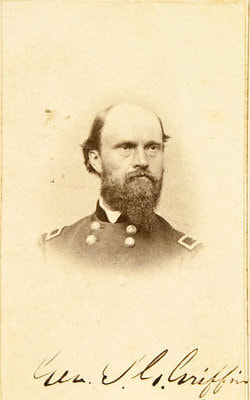

Brig. Gen. Simon Goodell Griffin

Brig. Gen. Simon Goodell Griffin

Though night attacks are open to many objections and their success is problematical at best night marches can often be made by which a force may be put in position to attack at early dawn In this manner Daun surprised Frederick the Great in the early morning at Hochkirch October 14 1758 and other striking instances of this method of attack are not lacking

At Petersburg June 17 1864 a similar attack at early dawn upon the redans and lines on the ridge near the Shand house was made with complete success. General Griffin who commanded the two brigades engaged in the assault describes it as follows:

“I spent the entire night moving my troops through the felled timber getting them in proper position and preparing for the attack I placed my brigade on the left of the Second Corps in a ravine immediately in front of the Shand house which the enemy held and within one hundred yards of their lines with Curtin on my left and a little further to the rear on account of the conformation of the ground. We were so near the enemy that all our movements had to be made with the utmost care and caution, canteens were placed in knapsacks to prevent rattling, and all commands were given in whispers. I formed my brigade in two lines Colonel Curtin formed his in the same way. My orders were not to fire a shot but to depend wholly on the bayonet in carrying the lines. Just as the dawn began to light up the east, I gave the command Forward. It was passed along the line in whispers. the men sprang to their feet, and both brigades moved forward at once in well-formed lines, sweeping directly over the enemy’s works, taking them completely by surprise and carrying all before us. One gunner saw us approaching and fired his piece. This was all we heard from them and almost the only shot fired on either side. The rebels were asleep with their arms in their hands and many of them sprang up and ran away as we came over. Others surrendered without resistance. We swept their line for a mile from where my right rested gathering in prisoners and abandoned arms and equipments all the way. Four pieces of artillery with caissons and horses, a stand of colors 600 prisoners, 1, 500 stand of arms, and some ammunition fell into our hands.”

At Petersburg June 17 1864 a similar attack at early dawn upon the redans and lines on the ridge near the Shand house was made with complete success. General Griffin who commanded the two brigades engaged in the assault describes it as follows:

“I spent the entire night moving my troops through the felled timber getting them in proper position and preparing for the attack I placed my brigade on the left of the Second Corps in a ravine immediately in front of the Shand house which the enemy held and within one hundred yards of their lines with Curtin on my left and a little further to the rear on account of the conformation of the ground. We were so near the enemy that all our movements had to be made with the utmost care and caution, canteens were placed in knapsacks to prevent rattling, and all commands were given in whispers. I formed my brigade in two lines Colonel Curtin formed his in the same way. My orders were not to fire a shot but to depend wholly on the bayonet in carrying the lines. Just as the dawn began to light up the east, I gave the command Forward. It was passed along the line in whispers. the men sprang to their feet, and both brigades moved forward at once in well-formed lines, sweeping directly over the enemy’s works, taking them completely by surprise and carrying all before us. One gunner saw us approaching and fired his piece. This was all we heard from them and almost the only shot fired on either side. The rebels were asleep with their arms in their hands and many of them sprang up and ran away as we came over. Others surrendered without resistance. We swept their line for a mile from where my right rested gathering in prisoners and abandoned arms and equipments all the way. Four pieces of artillery with caissons and horses, a stand of colors 600 prisoners, 1, 500 stand of arms, and some ammunition fell into our hands.”

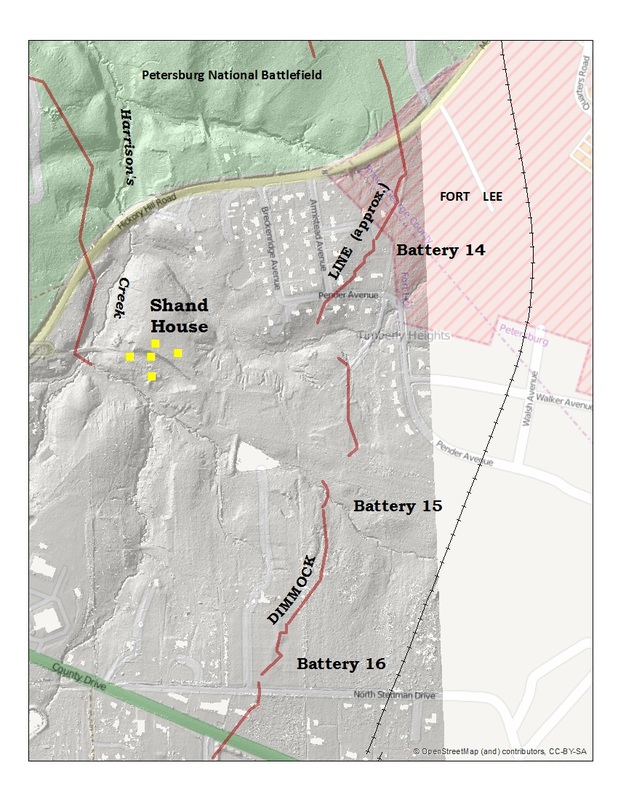

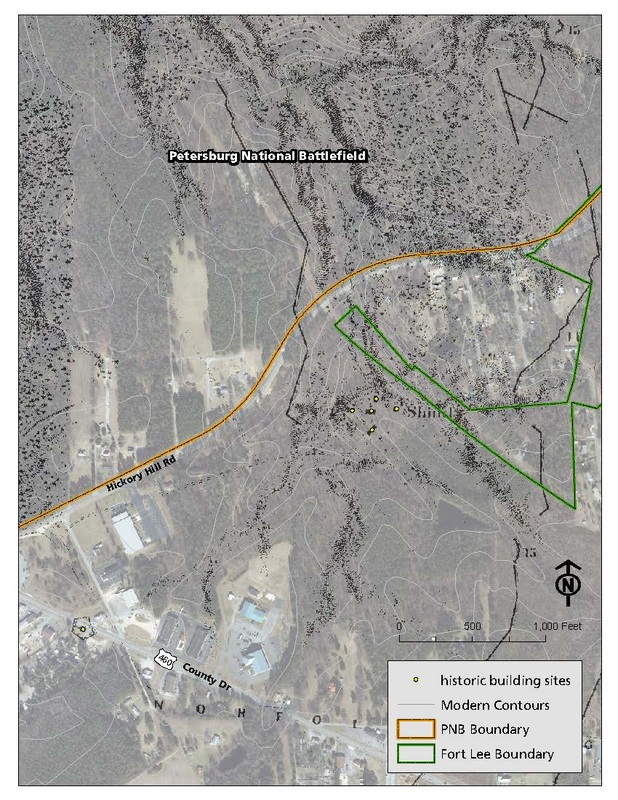

20th MichiganJune 16.— "'We marched all night in the direction of Petersburg; halted at 8 a. m. for coffee; rested till 10 a. m.; marched to within four miles of Petersburg, and formed line of battle in support of the First Brigade. The regiments went on picket, skirmishing all night.' ... [The pontoon bridge over Jame River] was located near Fort Powhattan or Wilcox's Landing, and the corps after crossing, marched on the road to Old Prince George Court House, and thence by the most direct road, coming upon the Petersburg line east of Harrison Creek and between the "Dunn House" and the Shand House, the interval corresponding with the line afterward included between Fort Stedman and Fort Morton. The Eighteenth Corps had carried the extreme right of the enemy's line from Appomattox River to near the Dunn House, on the 15th. On the 16th the Second Corps had advanced and seized the Hare House on the high hill where Fort Stedman was afterward built. The Shand House stood on the east side of Harrison Creek, and three-fourths of a mile due east of the site of Fort Morton. Harrison Creek took its rise on the Shand place in an almost impervious swamp, and flowed nearly due north about parallel with the Confederate lines, and emptied into the Appomattox River between Fort McGilvery and Battery V.

|

Coffin

"About half a mile south of Mr. Dunn was the residence of Mr. Shand, held by the rebels ... The house was a large two-story structure, fronting east, painted white, with great chimneys at either end, shaded by buttonwoods and gum trees, and a peach orchard in rear. Fifty paces from the front door was a narrow ravine, fifteen or twenty feet deep, with a brook, fed by springs, trickling northward. West of the house, about the same distance, was another brook, the two adjoining about twenty rods north of the house. A rebel brigade held this tongue of land, with four guns beneath the peach trees.Their main line of breastworks were along the edge of the ravine east of the house. South, and on higher ground, was a redan -- a strong work with two guns that enfiladed the ravine.Yet General Burnside thought that if he could get his troops into line unperceived, he could take the tongue of land, which would break the rebel line and compel them to evacuate the redan." Charles Carleton Coffin (as quoted in Oliver Christian Bosbyshell, The Forty Eighth [PA] in the War, pages 159-160

11th New Hampshire

A History of the Eleventh New Hampshire Regiment Volunteer Infantry , Leander W. Cogswell, 1891, across from page 356.

A History of the Eleventh New Hampshire Regiment Volunteer Infantry , Leander W. Cogswell, 1891, across from page 356.

"After a short rest the march was resumed and a little past noon the Ninth Corps was in position on the extreme left of the army ready for an assault upon the enemy’s works which were the outposts for the defence of Petersburg. The Second Corps was to make the assault assisted by the Second Division of the Ninth Corps. General Griffin with his brigade reported to General Barlow of the Second Corps and at 6 p. m. the advance was made in the face of a murderous fire The Eleventh and Second Maryland succeeded in getting close under a rebel battery. They were soon after joined by the Sixth and Ninth New Hampshire and later by the remainder of the brigade. The firing was continuous for several hours, and many men were wounded and a few killed.

At midnight General Griffin received an order to carry the works by assault, the troops to be ready to move at 3 a.m. The Eleventh New Hampshire, the Seventeenth Vermont, and the Thirty first Maine were detailed to make the charge supported by the Sixth and Ninth New Hampshire, the Second Maryland, and the Thirty second Maine. The men were divested of everything that would make unnecessary noise and as the watch ticked three o’clock with a bright dawn in the east the order was silently given to advance. Forward the men went with a stealthy quick step. The top of the little knoll was gained and with a rush the little plain was crossed. The men jumped upon the intrenchments before the enemy had time even to discharge their guns already loaded. Surrender you d----d rebels shouted Lieutenant Frost in the face of twenty guns levelled at him. In five minutes from the time the advance was begun, the fort was ours with its four guns, four stands of colors, twenty four horses, six hundred men, and fifteen hundred stands of small arms. It was one of the finest assaults of the whole war. Lieutenant Dimick of Company H was taken prisoner and several were wounded, among them Sergeant Will C Wood of Company H. As soon as the works had been taken, the brigade pushed on for the crest of a hill a short distance away, but just as the open plain near it was reached, a terrific fire was opened from masked batteries, and the troops fell back to the line that had been captured. The fighting this day was mostly done by the Ninth Corps assisted by a portion of the Fifth and Second corps. All the lines captured in the early morning were held and intrenched.

---Leander W. Cogswell, A History of the Eleventh New Hampshire Regiment, 1891, 376-377.

At midnight General Griffin received an order to carry the works by assault, the troops to be ready to move at 3 a.m. The Eleventh New Hampshire, the Seventeenth Vermont, and the Thirty first Maine were detailed to make the charge supported by the Sixth and Ninth New Hampshire, the Second Maryland, and the Thirty second Maine. The men were divested of everything that would make unnecessary noise and as the watch ticked three o’clock with a bright dawn in the east the order was silently given to advance. Forward the men went with a stealthy quick step. The top of the little knoll was gained and with a rush the little plain was crossed. The men jumped upon the intrenchments before the enemy had time even to discharge their guns already loaded. Surrender you d----d rebels shouted Lieutenant Frost in the face of twenty guns levelled at him. In five minutes from the time the advance was begun, the fort was ours with its four guns, four stands of colors, twenty four horses, six hundred men, and fifteen hundred stands of small arms. It was one of the finest assaults of the whole war. Lieutenant Dimick of Company H was taken prisoner and several were wounded, among them Sergeant Will C Wood of Company H. As soon as the works had been taken, the brigade pushed on for the crest of a hill a short distance away, but just as the open plain near it was reached, a terrific fire was opened from masked batteries, and the troops fell back to the line that had been captured. The fighting this day was mostly done by the Ninth Corps assisted by a portion of the Fifth and Second corps. All the lines captured in the early morning were held and intrenched.

---Leander W. Cogswell, A History of the Eleventh New Hampshire Regiment, 1891, 376-377.

9th New Hampshire

"Soon after dark the brigade was sent by regiments into the ravine which skirted the front of the Shand house, the Ninth occupying a position immediately in front of the house and hardly fifty paces from it and the Confederate line of works. Though close to danger the men were so fatigued that during the early hours of the night some of them even managed to sleep a little for the extreme heat of the night was rendered much more oppressive by the enforced stillness demanded by their advanced position. With the coming of the first faint tokens of the morning, however every man was on the alert and as the word to advance was passed along the lines anticipation of the work before them tightened the grip on the musket. Orders had been issued that the works were to be carried if possible by a bayonet charge and in the thick darkness of the ravine the ranks of bristling steel were softened by the faint shimmers of moonlight that sifted through the tree tops. Silently yet swiftly the long dark line rises above the bank and sweeps down upon the unsuspecting and sleeping foe. So sudden has been the onset that the enemy make but little resistance and there is very little bloodshed on either side while the reward for valor far outshines the risk. The Second brigade with its force of less than a thousand men has carried the earthworks in its front and has captured about four hundred prisoners including fifteen officers together with the colors of the Fifty third Tennessee and three guns of the Baltimore light artillery, an exploit of which they may well be proud. This ended active movements for the Ninth New Hampshire for the day though they were detailed to occupy the front line for some little time after the charge. On being relieved they were ordered back to the shelter of the ravine and rested quietly during the day and the following night. The casualties of the regiment in this charge counted up fifteen wounded a few of them mortally."

--Edward O. Lord, History of the Ninth Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers, 1895, 451-452.

--Edward O. Lord, History of the Ninth Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers, 1895, 451-452.

"Another landmark of the siege was the Shands house, which stood about a mile east of Spring Garden. The house is reputed to have been built in the style of an English country manor, on land granted by the crown to

William Shands. At the time the Union army appeared east of Petersburg in June 1864, the occupants of the house were Sally Rives Shands and her husband, Elijah Monroe Webb. Taking heed of a Union soldier's warning,

the young couple fled, leaving just about everything behind. Later in 1864 the house, or site, was used as a headquarters by General Winfield S. Hancock, commanding the Union Second Army Corps. The date of its destruction is uncertain, but it had been destroyed by the end of the siege. A new dwelling was erected by the family on another site, and for many years their tract of land has been known as Hickory Hill."

From A HISTORY OF PETERSBURG NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD by Lee A. Wallace, Jr. and Martin R. Conway 1983.

William Shands. At the time the Union army appeared east of Petersburg in June 1864, the occupants of the house were Sally Rives Shands and her husband, Elijah Monroe Webb. Taking heed of a Union soldier's warning,

the young couple fled, leaving just about everything behind. Later in 1864 the house, or site, was used as a headquarters by General Winfield S. Hancock, commanding the Union Second Army Corps. The date of its destruction is uncertain, but it had been destroyed by the end of the siege. A new dwelling was erected by the family on another site, and for many years their tract of land has been known as Hickory Hill."

From A HISTORY OF PETERSBURG NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD by Lee A. Wallace, Jr. and Martin R. Conway 1983.