The Grand Medicine Pow-wow, August 3, 1864:

Federal Engineers Redesign Petersburg's Siegeworks

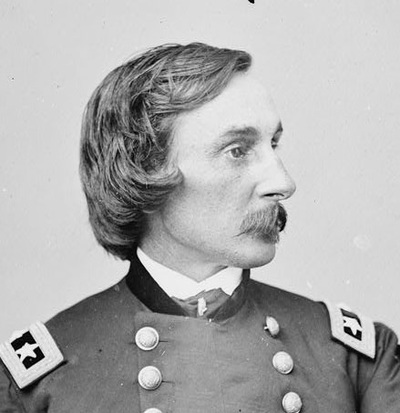

Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, Meade's A.D.C.

Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, Meade's A.D.C.

"August 3, 1864, Wednesday. Grand medicine pow-wow over the “second line” by the Engineers. Humphreys, Warren, Duane, old Barnard, Michler, and Mendel, all dabbing on maps with their fingers."

-- Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, Meade's Army, pg. 245

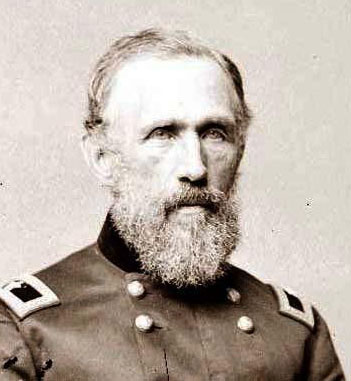

Gilbert Thompson, topographical engineer

Gilbert Thompson, topographical engineer

August 1. About this date a new line of fortifications was planned, intended to rectify the battle-line, and so enable it to be held with less force. It was also planned to enlarge Fort Sedgwick, and to construct between the Appomattox River and Fort Sedgwick six strong works, each capable of independent defense: Forts Haskell, McGilvery, Stedman, Morton, Rice, and Meikle; some of which, however, were already in use as batteries, etc. A connecting line of rifle-pits was laid out by Captain Harwood.

-- Diary of Gilbert Thompson, topographical engineer

|

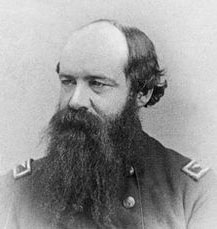

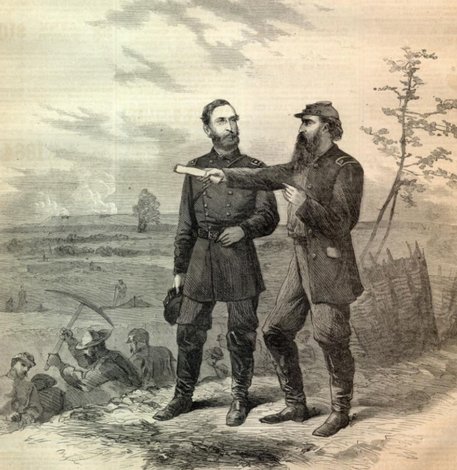

"General Hunt and Major Duane, Chief of Artillery and Chief Engineer, Army of the Potomac," woodcut from a sketch by special artist A. R. Waud. Harpers Weekly, October 15, 1864.

"WE give on this page sketches of Brigadier-General HUNT and Major DUANE, the former Chief of Artillery, and the latter Chief Engineer of the Army of the Potomac. Both are soldiers of the first class. HENRY J. HUNT entered the Military Academy at West Point from Ohio in 1835. He graduated with the rank of Second Lieutenant of Artillery. In 1846 he was appointed First Lieutenant. He commanded a section of DUNCAN'S Battery in the Valley of Mexico. For meritorious conduct in the battles of Contreras and Churubusco he was raised by brevet to the rank of Captain, and subsequently to that of Major. At El Molino he was wounded. JAMES C. DUANE graduated from West Point in 1844 [1848] with the rank of Second Lieutenant of Engineers. The responsible position held by General HUNT and Major DUANE is sufficient testimony to their worth and soldierly ability. The siege operations of General Grant's campaign—which, although they do not attract public attention, are yet of the greatest importance—have been principally conducted by these officers." |

Report of Col Nathaniel Michler , Official Records, Series 3, Vol. 5, pg. 173

"Upon the explosion of the mine [July 30, 1864] and failure of the assault the troops engaged were directed on the following day to resume their previous positions to a great extent, some few changes being ordered for the purpose of reducing their fronts and establishing reserves for ulterior movements. The plan of the siege by regular approaches having been abandoned, Colonel Michler was directed at the same time to make such a disposition of the lines then occupied by the corps as would enable them to be held by a diminished force, and therefore determined to select an interior line, to consist of some few detached, inclosed works, subsequently to be connected by lines of infantry parapets. The first line selected was one lying on very commanding ground, and extending from the present Fort Sedgwick to the Rushmore house, immediately opposite Fort Clifton, one of the enemys works on the Appomattox, at the head of navigation for large sea-going vessels, passing near the Avery, Friend, Dunn, and Jordan houses. This being considered too far to the rear of the then advanced position, and apparently yielding too much ground, for the possession of which such desperate fighting had taken place, he finally chose an intermediate one, and sites for Forts Rice, Meikel, Morton, Haskell, Stedman, and McGilvery were selected, and the intervening batteries and lines located. It had also been decided to enlarge and strengthen the lunette, the site of which is now occupied by Fort Sedgwick. By direction of Lieutenant-General Grant the supervision of the line in front of the Eighteenth Corps had also been placed under his direction. The construction of these different works was pushed rapidly forward by night, under the immediate charge of Captains Gillespie and Harwood and Lieutenants Howell, Benyaurd, and Lydecker, as much so as the sparsity of officers, the extreme heat of the weather, and the heavy and constant artillery fire of the enemy would permit. Several officers of the Corps of Engineers, including Captains Mendell, Turnbull, and Farquhar, had been ordered away from the army on other duty, and some of the lieutenants were absent on sick leave. By the 20th of August the works were so near completion as to be in readiness for the contemplated movement on the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad."

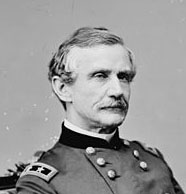

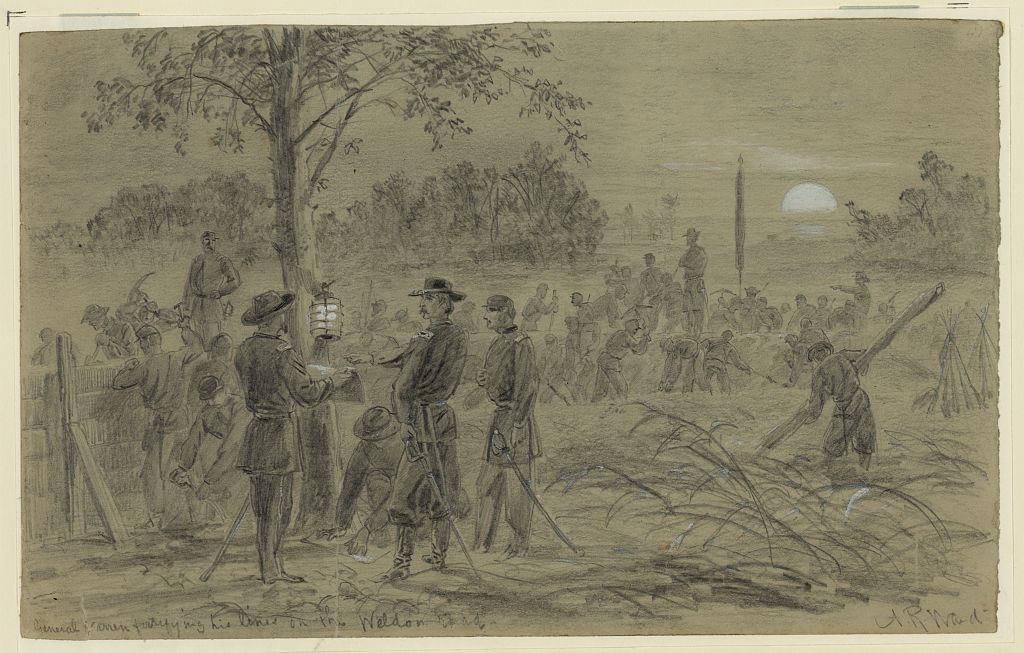

LC 3g12599. "General Warren fortifying his lines on the Weldon road," drawing by A. R. Waud. G. K. Warren was never so happy as when supervising the construction of earthworks. During the Grand Medicine Pow-wow, Warren drove home the point that the army could not afford to abandon acres of ground that had been "bought with blood" only to form a perfect defensive line. Warren was an unsung architect behind the Petersburg siegeworks.

Importance of the Grand Medicine Pow-wow by Dr. Philip Shiman

I wrote up a short statement of our main points to make in the article and a chronology (which I've attached). All well & good. But then I started to look through the documents and began to see things I hadn't seen before. The keys were Lyman's description of the "Grand medicine pow-wow" and a report by Michler that I had overlooked (it was extracted from his main reports and published separately in Series III of the ORs). They unlocked for me the story (much of it, anyway) of how that line was planned. I think I can reconstruct what the pow-wow was all about, at least as a hypothesis.

The story begins with the construction of the Plank Road flank line in July. At this time Grant and Meade were wrestling with what to do. The three choices were: Open assault; attack by regular approaches; and reach around Lee's army to attack his communications. None of these options was very attractive. The disaster at Jerusalem Plank Road & the loss of the Sixth Corps put the kibosh on the reach-around strategy. Of the other two, Grant wanted to attack on the Ninth Corps front, because of the mine & Burnside's optimism; Meade & his engineers wanted regular approaches on Warren's front. So they kind of hemmed & hawed about this for the next several weeks.

Meanwhile, at the start of July, Meade was very nervous about his flank, since he knew he may lose the Sixth and even Second Corps, which were holding the left of his line. He was convinced that if he attacked on Burnside's front and was repulsed, Lee could come sweeping around his open flank, so he told Warren to think about building a new line there. On July 4 Warren asked permission to build a redoubt where the angle would be; this was the future Fort Davis. The next day he suggested that in addition to this "small redoubt" (hah!) they build another one, the future Fort Prescott. (The connecting rifle pits were an afterthought; Warren himself said there is little urgency for them.) A few days later the line was extended back to the Blackwater Swamp and Fort Bross laid out. Meade placed such a high priority on this work that he assigned nearly all his regular engineers to it--seven officers, including Duane.

Warren was very particular about the work. He devoted his energy to it and, in his words, made himself "general of the trenches." He fussed with the engineers and even with his own brigade commanders. After a week the engineers turned Fort Davis over to him to finish, probably because they were sick of his micromanaging. After about two weeks they finished this line, which is, by the way, the prototype for the "redoubt & riflepit" form used later.

(Side anecdote: Warren told an engineer working on his front that Fererro, who's division is posted there, was complaining that his troops are having to do so much of the construction. The engineer replied that it's because "A negro is worth two, if not three, white men to dig.” Evidently Warren thought that over, because a few days later he recommended to army headquarters "that General Ferrero's command be detailed as engineer soldiers during the siege.”)

After the Battle of the Crater, neither another assault nor regular approaches were viable, so by default Grant & Meade turned back to the reach-around strategy. The army had really shrunk by then, so the emphasis was on reducing the lines to a bare bones. The next day Meade ordered Michler (the acting chief engineer) to "make such a disposition of the lines of the Fifth and Ninth Corps as will enable them to be held by a diminished force," and he ordered Burnside & Warren to "make their lines conform to the project of the acting chief engineer." Michler apparently already had in mind a line of redoubts, because Lyman said on the 31st: "Surveys going on for a rear line, to shorten the old one, and, with the redoubts, to be held by much fewer men." Michler himself said that he "determined to select an interior line, to consist of some few detached, inclosed works, subsequently to be connected by lines of infantry parapets.”

A couple of days later, on August 2nd, Warren, who wasn't happy about the project, asked Meade to give him more of a say in it and control of the work on his own front. He wanted the engineers working there to report to him and to camp with his troops "that they may then have the deepest personal interest in their work; there has already been a good deal of unnecessary labor spent and I cannot afford more." (What is he implying here...?) He also pointedly said, "I have necessarily other work and ideas of defense than engineer officers, and if they cannot work under my orders they are more of an injury to me now than a benefit.” Clear conflict here.

I think the real sticking point was the location of the new line, because Warren's first demand was to "be consulted in the location of the new defensive works." Michler apparently had already chosen a line: the old Confederate Dimmock Line, which he had previously surveyed & considered a "beautifully planned and constructed" position on "a most magnificent and commanding" site. (The Dimmock Line faced east, but it is pretty strong facing west too, maybe even stronger.) This didn't sit well with Warren, who had his own plans for strengthening his front with a second line (he's worried about Confederate mining at Ft. Hell). Michler's plan would have abandoned Warren's position entirely. There were other reasons to oppose Michler's plan as well, both practical and psychological: It meant giving up hard-won ground. As he said himself, his chosen line was "considered too far to the rear of the then advanced position, and apparently yielding too much ground, for the possession of which such desperate fighting had taken place." (I think Warren was probably right: Michler's line was too far back and gave up too much useful ground.)

Meade refused to give Warren control over the engineers but said he was "ready to receive any suggestions you may have to make in regard to their operations and to decide all points of difference that may arise." He added that "the chief engineer was directed to confer with corps commanders.” Warren jumped at this chance to get his two cents in because the Grand Medicine Pow-wow happened the next day.

I think I now understand what was going on, and what Humphreys was doing there. Warren went to lean on the engineers. Michler, who was on the defensive, had his most senior colleagues there for support: Duane (who for some reason was no longer running things-- there must be a story there), Mendell, and even "old Barnard," who nobody took seriously anymore but at least he had a star on his shoulder and was (nominally) still on Grant's staff. However, even with Barnard, the engineers were outgunned by Warren, a major general. That may at least partly be why Humphreys was there. He of course represented army headquarters and would ultimately decide disputes like this; he understood Meade thoroughly and like his boss was conservative by nature. But I think he may have also been there to level the playing field, since the engineers could not really stand up to Warren by themselves (and there was no reason they should have to, they weren't in the chain of command). Humphreys was the referee who would make sure it was a fair fight and ultimately decide the winner.

In any event, after much arguing and "dabbing on maps with their fingers," Warren got his way, and an "intermediate" line was chosen (the one that was built). Fort Sedgwick was expanded into a powerful salient, which is also what Warren wanted. In the end, Michler got a consolation prize: He built two independent redoubts along his preferred line, at the Friend and Avery houses.

That is my story for now. To be revised and updated at my discretion. .... P. Shiman, August 2008

The story begins with the construction of the Plank Road flank line in July. At this time Grant and Meade were wrestling with what to do. The three choices were: Open assault; attack by regular approaches; and reach around Lee's army to attack his communications. None of these options was very attractive. The disaster at Jerusalem Plank Road & the loss of the Sixth Corps put the kibosh on the reach-around strategy. Of the other two, Grant wanted to attack on the Ninth Corps front, because of the mine & Burnside's optimism; Meade & his engineers wanted regular approaches on Warren's front. So they kind of hemmed & hawed about this for the next several weeks.

Meanwhile, at the start of July, Meade was very nervous about his flank, since he knew he may lose the Sixth and even Second Corps, which were holding the left of his line. He was convinced that if he attacked on Burnside's front and was repulsed, Lee could come sweeping around his open flank, so he told Warren to think about building a new line there. On July 4 Warren asked permission to build a redoubt where the angle would be; this was the future Fort Davis. The next day he suggested that in addition to this "small redoubt" (hah!) they build another one, the future Fort Prescott. (The connecting rifle pits were an afterthought; Warren himself said there is little urgency for them.) A few days later the line was extended back to the Blackwater Swamp and Fort Bross laid out. Meade placed such a high priority on this work that he assigned nearly all his regular engineers to it--seven officers, including Duane.

Warren was very particular about the work. He devoted his energy to it and, in his words, made himself "general of the trenches." He fussed with the engineers and even with his own brigade commanders. After a week the engineers turned Fort Davis over to him to finish, probably because they were sick of his micromanaging. After about two weeks they finished this line, which is, by the way, the prototype for the "redoubt & riflepit" form used later.

(Side anecdote: Warren told an engineer working on his front that Fererro, who's division is posted there, was complaining that his troops are having to do so much of the construction. The engineer replied that it's because "A negro is worth two, if not three, white men to dig.” Evidently Warren thought that over, because a few days later he recommended to army headquarters "that General Ferrero's command be detailed as engineer soldiers during the siege.”)

After the Battle of the Crater, neither another assault nor regular approaches were viable, so by default Grant & Meade turned back to the reach-around strategy. The army had really shrunk by then, so the emphasis was on reducing the lines to a bare bones. The next day Meade ordered Michler (the acting chief engineer) to "make such a disposition of the lines of the Fifth and Ninth Corps as will enable them to be held by a diminished force," and he ordered Burnside & Warren to "make their lines conform to the project of the acting chief engineer." Michler apparently already had in mind a line of redoubts, because Lyman said on the 31st: "Surveys going on for a rear line, to shorten the old one, and, with the redoubts, to be held by much fewer men." Michler himself said that he "determined to select an interior line, to consist of some few detached, inclosed works, subsequently to be connected by lines of infantry parapets.”

A couple of days later, on August 2nd, Warren, who wasn't happy about the project, asked Meade to give him more of a say in it and control of the work on his own front. He wanted the engineers working there to report to him and to camp with his troops "that they may then have the deepest personal interest in their work; there has already been a good deal of unnecessary labor spent and I cannot afford more." (What is he implying here...?) He also pointedly said, "I have necessarily other work and ideas of defense than engineer officers, and if they cannot work under my orders they are more of an injury to me now than a benefit.” Clear conflict here.

I think the real sticking point was the location of the new line, because Warren's first demand was to "be consulted in the location of the new defensive works." Michler apparently had already chosen a line: the old Confederate Dimmock Line, which he had previously surveyed & considered a "beautifully planned and constructed" position on "a most magnificent and commanding" site. (The Dimmock Line faced east, but it is pretty strong facing west too, maybe even stronger.) This didn't sit well with Warren, who had his own plans for strengthening his front with a second line (he's worried about Confederate mining at Ft. Hell). Michler's plan would have abandoned Warren's position entirely. There were other reasons to oppose Michler's plan as well, both practical and psychological: It meant giving up hard-won ground. As he said himself, his chosen line was "considered too far to the rear of the then advanced position, and apparently yielding too much ground, for the possession of which such desperate fighting had taken place." (I think Warren was probably right: Michler's line was too far back and gave up too much useful ground.)

Meade refused to give Warren control over the engineers but said he was "ready to receive any suggestions you may have to make in regard to their operations and to decide all points of difference that may arise." He added that "the chief engineer was directed to confer with corps commanders.” Warren jumped at this chance to get his two cents in because the Grand Medicine Pow-wow happened the next day.

I think I now understand what was going on, and what Humphreys was doing there. Warren went to lean on the engineers. Michler, who was on the defensive, had his most senior colleagues there for support: Duane (who for some reason was no longer running things-- there must be a story there), Mendell, and even "old Barnard," who nobody took seriously anymore but at least he had a star on his shoulder and was (nominally) still on Grant's staff. However, even with Barnard, the engineers were outgunned by Warren, a major general. That may at least partly be why Humphreys was there. He of course represented army headquarters and would ultimately decide disputes like this; he understood Meade thoroughly and like his boss was conservative by nature. But I think he may have also been there to level the playing field, since the engineers could not really stand up to Warren by themselves (and there was no reason they should have to, they weren't in the chain of command). Humphreys was the referee who would make sure it was a fair fight and ultimately decide the winner.

In any event, after much arguing and "dabbing on maps with their fingers," Warren got his way, and an "intermediate" line was chosen (the one that was built). Fort Sedgwick was expanded into a powerful salient, which is also what Warren wanted. In the end, Michler got a consolation prize: He built two independent redoubts along his preferred line, at the Friend and Avery houses.

That is my story for now. To be revised and updated at my discretion. .... P. Shiman, August 2008

|

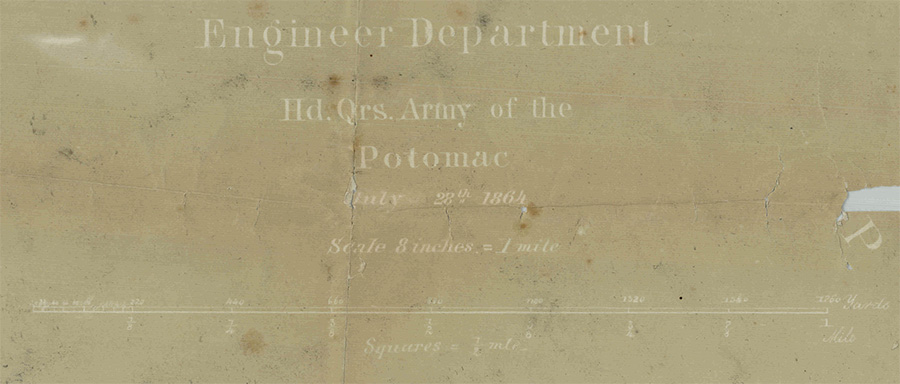

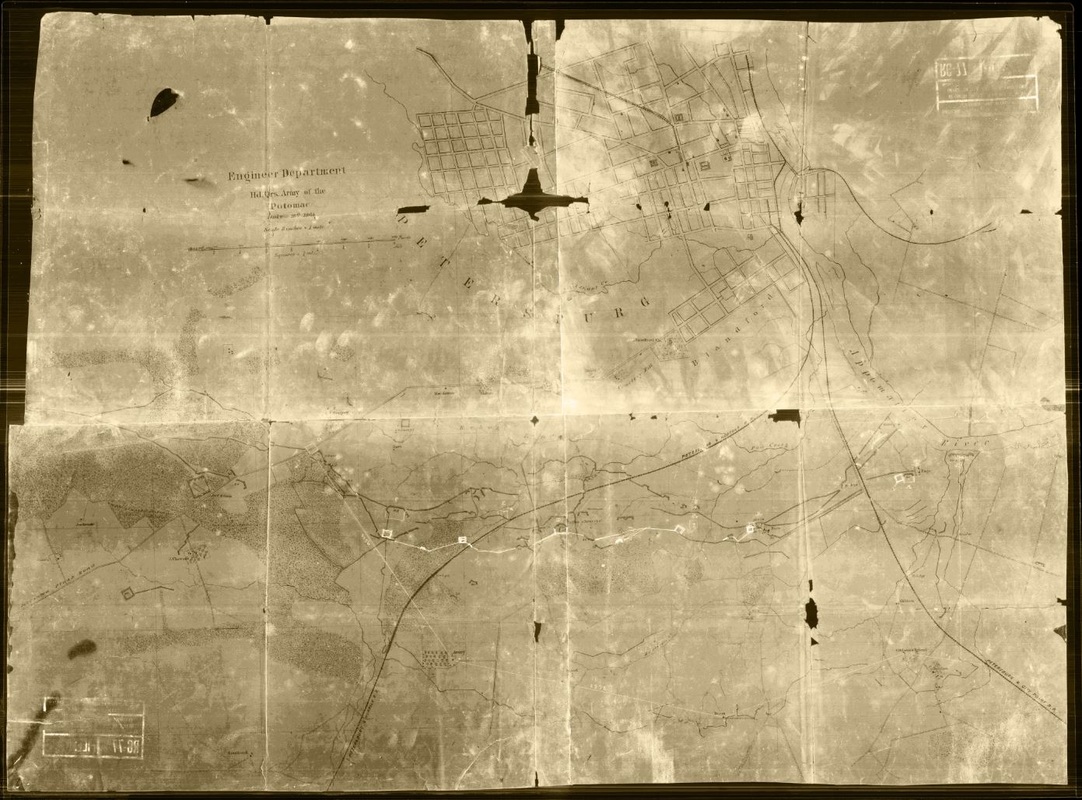

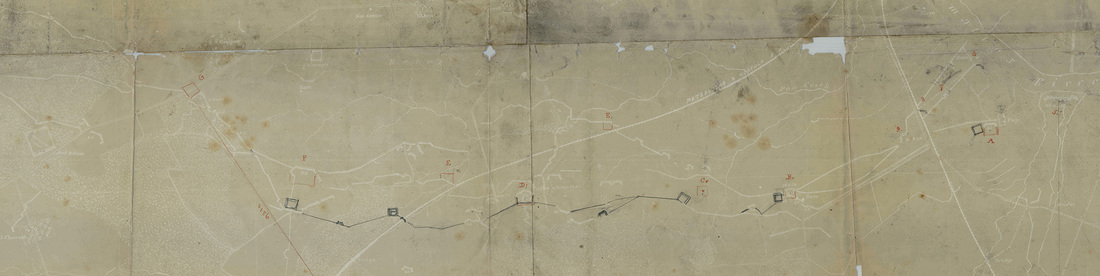

This manuscript map from the National Archives shows the evolutions of the Federal lines on the Eastern Front at Petersburg. The map was annotated to depict the locations of Federal regiments during the battle of Fort Stedman, March 25, 1865. The green highlighting shows original Confederate lines, including rapid entrenchments from the opening battles of the siege in June 1864. Red lines show various Federal arrangements through June and August, 1864, leading up to the final configurations decided upon after the Grand Medicine Pow Wow shown in blue. Earlier works were typically maintained as advanced picket lines and coehorn batteries.

Duane's Reasoning ... at a later date?Dec. 8th, 1864. "Col. Duane was very communicative last night. Never found him so much so. He told me that the present line of work in front of Petersburgh was not planned by him. It was not planned by anybody. Our troops went as far as they could, and stopped and fortified where they were. Duane would have build three great bastioned forts, each large enough to hold 3000 men, and garrisoned them. The main army might then have lain in reserve and been ready for any desired operations. Sensible I say." --William Watts Folwell, 50th New York Engineers. |

Report of Capt. Henry L. Abbot, Official Records Vol. 46, part 1, 173

"On March 25 [1865] an event occurred which well illustrated the advantages of the system of fortifications adopted by Colonel Duane, chief engineer, Army of the Potomac. This system consists, in general terms, of a series of small field-works, capable of containing a battery of artillery and an infantry garrison of some 200 men each. They are closed at the gorge, well-protected with abatis or palisading, often supplied with bomb-proofs, and placed at intervals of about half a mile, on such ground as to well sweep the line in front with artillery fire. They are connected by strong, continuous infantry parapets, protected in front by obstacles. They differ from those of the rebel line chiefly in being closed at the gorge, which is rarely the case with the latter. Fort Stedman is one of the weakest and most ill-constructed works of the line, being not protected by abatis in rear, being masked on its right (just in rear of Battery No. 10) by a mass of bomb-proofs, rendered necessary by the terrible fire which has habitually had place in this vicinity, and being only about 200 yards distant from the enemy’s main line. The parapet had settled greatly during the winter, and, in line, the work was very liable to being carried by a sudden assault. Company K, First Connecticut Artillery, served mortar batteries in Batteries 9 and 10, and Company L, First Connecticut Artillery, in Battery 12 and in Fort Haskell. At about 4 a. m. of March 25, three divisions of the rebels, under General Gordon, made a sudden and well-arranged attack upon this fort. It was a complete surprise, and was successful. Their columns simultaneously swept over the parapet between Stedman and Battery 9, over Battery 10, and over Battery 11, formed in rear of the fort, and carried it almost without opposition. From that time to daylight a hand-to-hand fight raged among the bomb-proofs and on the flanks of the enemy’s position. He assaulted Fort Haskell again and again, but failed to carry it, or Battery No. 9, which, unlike the others named, is closed at the gorge. As soon as the light would admit, all my own artillery from Batteries 4,5,8, 9, and Fort Haskell, and all the light artillery which General Tidball, chief of artillery, Ninth Corps, could concentrate upon the position, opened and maintained a terrible fire upon the enemy. No re-enforcements could join them across the plain, owing to this fire; their own position was entailing deadly loss upon them. The reserves of the line were rapidly assembling, and finally, about 8 a. m., made a gallant charge, which resulted in the recovery of our works, all our artillerymen, including my Coehorn mortars and in the capture of over 1,800 prisoners. The following extract from rebel papers show the effect of our artillery fire: ‘It was found that the enclosed works in the rear commanding the enemy’s main line could only be taken at a great sacrifice. The enemy massed his artillery so heavily in the neighboring forts, and was enabled to pour such a terrible enfilading fire upon our ranks, that it was deemed best to withdraw. The enemy enfiladed us from right and left in the captured works to such an extent that we could no longer hold them without the loss of many men, & c.’ If the enclosed works on right and left had not fixed a limit beyond which the enemy could not extend, I think a great disaster might have occurred; as it was, my regiments loss was heavy, being about sixty men." --Abbot