Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, Meade's A.D.C.

Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, Meade's A.D.C.

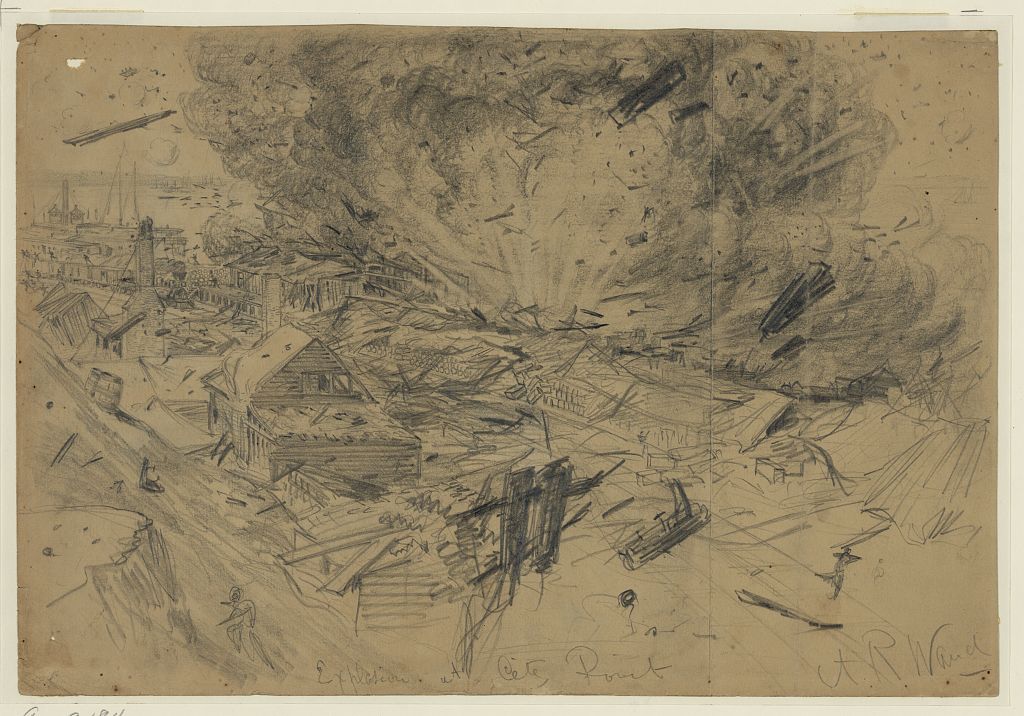

August 9, Tuesday. This morning we heard a heavy explosion towards City Point, and there came a telegraph in few minutes that an ordnance barge had blown up with much loss of life. “Rosie,” Worth, Cavada and Cadwalader were in a tent at Grant’s Headq’rs when suddenly there was a great noise, and a 12-pdr. shot came smash into the mess-chest! They rushed out —it was raining shot, shell, timbers and saddles (of which there had been a barge load near)! Two dragoons were killed near them. They saw just then a man running towards the explosion —the only one— it was Grant! and this shows his character well. About 35, mostly negro, lumpers, were killed, and 80 wounded. (The cause of this was never known. It was commonly thought, after, to have been a rebel torpedo.)

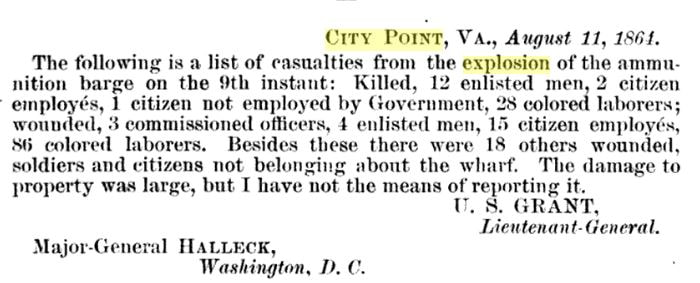

City Point, Va., August 9, 1864--11.45 a.m. [General Halleck:] Five minutes ago an ordnance boat exploded, carrying lumber, grape, canister, and all kinds of shot over this point. Every part of the yard used as my headquarters is filled with splinters and fragments of shell. I do not know yet what the casualties are beyond my own headquarters. Colonel Babcock is slightly wounded in hand and 1 mounted orderly is killed and 2 or 3 wounded and several horses killed. The damage at the wharf must be considerable both in life and property. As soon as the smoke clears away I will ascertain and telegraph you. --Grant

City Point Wharf Explosion, August 9, 1864

Ordnance officer J. P. Farley remembers the wharf explosion -- the horological torpedo

Lt. Joseph P. Farley, U.S. Military Academy, Class of 1861

Lt. Joseph P. Farley, U.S. Military Academy, Class of 1861

"As a retaliatory measure, following the Petersburg mine fiasco, the Confederate agents of the Secret Service Bureau undertook to destroy the depot of the Union Army at its headquarters, City Point, Virginia. The accompanying sketch shows very distinctly, General Grant seated on the left of the picture, in the deep shade of the overhanging trees, where he was at the time of the explosion. Two men (John Maxwell, the principal who was the inventor of the torpedo used) entered the Union lines at City Point and successfully placed a horological torpedo on one of the numerous ordnance barges, containing field gun ammunition and which at the time was being unloaded at the main wharf, 300 yards from the General commanding. The clockwork to initiate the explosion was set to run one hour, and when the explosion occurred about 11:30 A. M., on August 9th, it communicated to a second barge, exploding in all about five hundred tons of fixed ammunition. The resulting explosion was terrific– there was a total wreckage of the extended line of wharves and storehouses; the property destroyed being estimated by the Confederates at $4,000,000. While they reported the Union loss of life at 184 of which number 43 were killed outright.

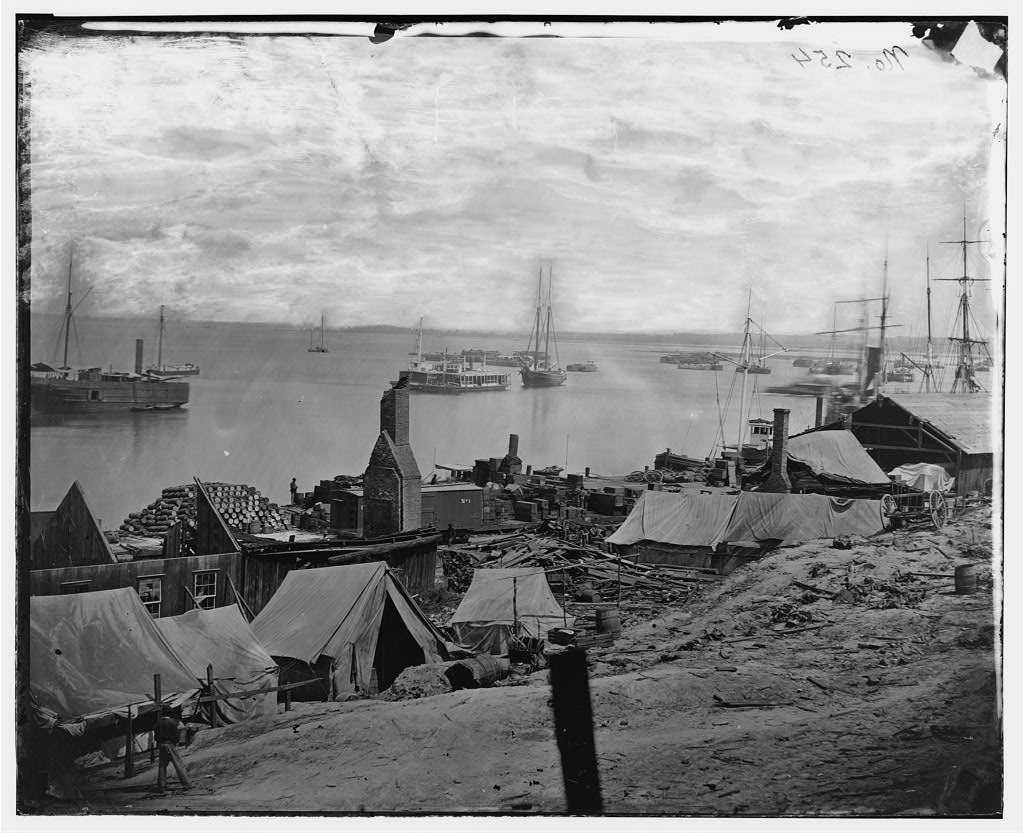

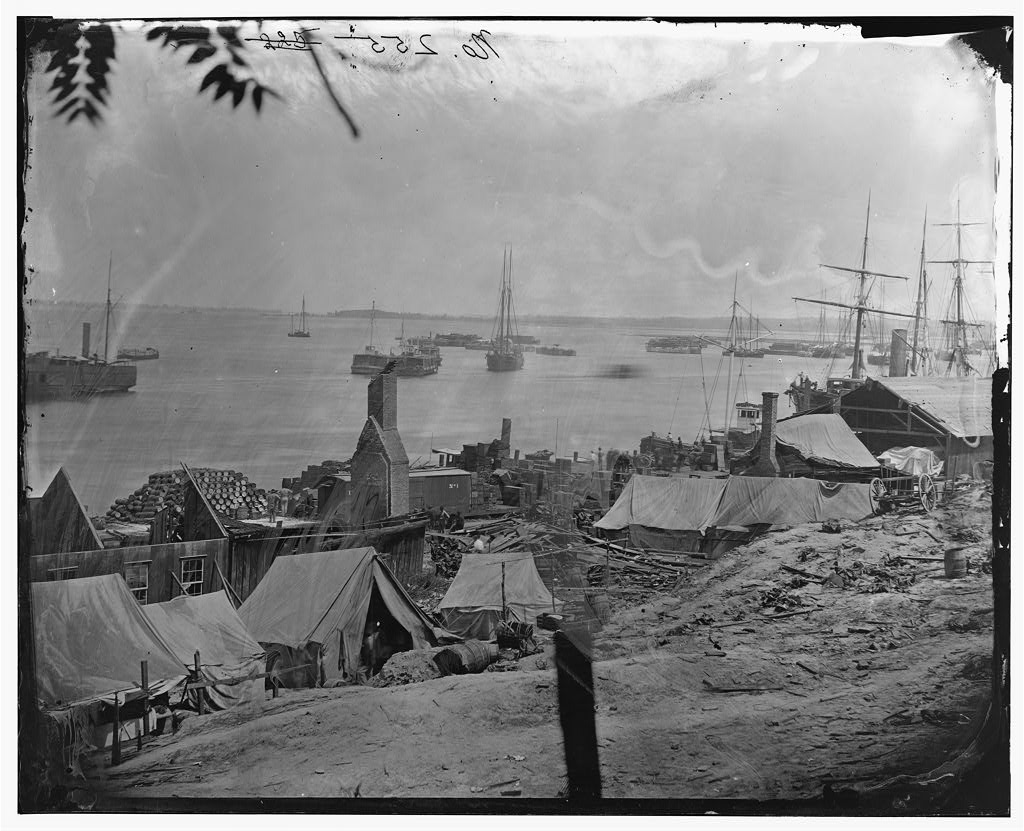

The long wharves and levees at that time outrivaled a San Francisco or a New Orleans in their prime; for it should be remembered that 150,000 men were drawing all their supplies from the City Point base of operations. The armies operating against Richmond were much crippled by this act. It was not known until many months after that the explosion was the work of the enemy, and since it had been ascribed to accident, great anxiety was felt by all lest there should be a recurrence of a similar nature. As a measure of precaution, General Grant directed me as his ordnance officer to remove the entire ordnance depot to the right flank of our base and as far away from the depot of supplies as the lay of the land would permit. One of the sketches made by me at that time, shows the site of the restored depot with some 50 vessels and barges. General Horace Porter, aide to General Grant, in his memoirs of the General, says: “That at the instant of the explosion, which was terrific and shook the earth like an earthquake, accompanied by a sound, vividly recalling the Petersburg mine, there rained down upon the headquarters of General Grant, a terrific shower of exploding shells, boards and fragments of timber. The ground was covered with various kinds of ammunition and splinters but, fortunately the General was not touched by any of the missiles. He was the only one of the Party who remained unmoved—one of his orderlies was killed and two wounded and Colonel Babcock, of the staff, was wounded in the hand. It was said that this was the narrowest escape with his life which the General met throughout the entire war." -- "Reminiscences," Army and Navy Life, vol. 12, no. 1 (Jan. 1908), pg. 478.

The long wharves and levees at that time outrivaled a San Francisco or a New Orleans in their prime; for it should be remembered that 150,000 men were drawing all their supplies from the City Point base of operations. The armies operating against Richmond were much crippled by this act. It was not known until many months after that the explosion was the work of the enemy, and since it had been ascribed to accident, great anxiety was felt by all lest there should be a recurrence of a similar nature. As a measure of precaution, General Grant directed me as his ordnance officer to remove the entire ordnance depot to the right flank of our base and as far away from the depot of supplies as the lay of the land would permit. One of the sketches made by me at that time, shows the site of the restored depot with some 50 vessels and barges. General Horace Porter, aide to General Grant, in his memoirs of the General, says: “That at the instant of the explosion, which was terrific and shook the earth like an earthquake, accompanied by a sound, vividly recalling the Petersburg mine, there rained down upon the headquarters of General Grant, a terrific shower of exploding shells, boards and fragments of timber. The ground was covered with various kinds of ammunition and splinters but, fortunately the General was not touched by any of the missiles. He was the only one of the Party who remained unmoved—one of his orderlies was killed and two wounded and Colonel Babcock, of the staff, was wounded in the hand. It was said that this was the narrowest escape with his life which the General met throughout the entire war." -- "Reminiscences," Army and Navy Life, vol. 12, no. 1 (Jan. 1908), pg. 478.

Excerpt from "Explosion at City Point," by Chief of Ordnance Capt. Morris Schaff

"On the 11th of August [sic], a few weeks later, the Confederates blew up the ordnance depot under my charge at City Point, killing over two hundred, wounding many, and fearfully maiming others, besides destroying over $2,000,000 of property. It is not a matter of any historic interest or value whatever, that I was playing "Seven-up" at the moment of the explosion, yet sometimes the bare facts of an event are most vividly realized and longest remembered through the small details that give them a real human interest. However this may be, on the morning of the explosion Captain, now Colonel, Evans of the regulars, came to my office just as I was leaving it to go down to the wharf. The house I occupied, a small one-story, broad hailed, frame building, stood on the bluff on the farther side of a little common, perhaps one hundred and fifty yards back from the wharf. Behind it was a garden.

The day was very hot, and knowing that my friend of the regulars was as dry as the rest of them that came down from the lines, I wished to show him the customary and most acceptable hospitality. I went to my demijohn and much to my surprise found it was empty. Evans must have looked especially despondent, for I said, "Come over to Grant's Headquarters; I know where I can get some," having in mind my friend Captain Mason of the 6th Regulars, who commanded Grant's escort. It was only a step, perhaps a hundred yards. When we reached the tent there we found ten or a dozen of Meade's and Grant's staff around a pail two-thirds full of claret punch. Among the rest was Captain, later Admiral, John Clitz of the United States Navy, one of the blithest hearted and most gallant men who ever trod a deck. His ship lay out in the river.

We had no sooner got there than Clitz, with whom I had had a very exciting game the day before, challenged me, and with Billy Worth (now General Worth, who was most severely wounded at Santiago) for his partner, and Captain Hudson of Grant's staff for mine, we began the game on Captain Mason's bed. I can't be certain how the game would have come out, but I had just captured two tens with a queen, which in all probability would have made the game at least, when the explosion took place and a 12-lb. solid shot crashed across the bed into Mason's camp mess-chest. Of course there was a sudden stampede. As there was something falling or shells bursting at every instant, I looked up to see what was coming next. The sky looked as it does in the fall of heavy snow flakes. Just then a shell burst immediately over us. In an instant we were all running for dear life. Clitz was the oldest and had complained of rheumatism while we were playing, in fact he had asked me to get him some more claret punch, declaring that it hurt him to walk; yet in the flight he was ahead of us all. Suddenly a piece of the shell came down over my left shoulder. I could have stepped on the hole it made in the ground, but it brought me to my senses, and I at once turned and made my way to the wharf.

From the top of the bluff there lay before me a staggering scene, a mass of overthrown buildings, their timbers tangled into almost impenetrable heaps. In the water were wrecked and sunken barges, while out among the shipping — where were many vessels of all sizes and kinds — there was hurrying back and forth on the decks to weigh anchor, for all seemed to think that something more would happen. I at once went down to the ruined building, a large frame structure six hundred feet long, under the charge of my Sergeant, Harris, an old regular and one of the gentlest and most faithful and honest men I ever knew. I could hear the cries of some of the men, and soon heard Corporal Bradley call out, "For God's sake, Captain, come and help me out." He was pinned down under some heavy timbers with one of his legs crushed. It was amputated, and I saw him after the war at West Troy, New York. Later, I found Sergeant Harris lying on his back dead, with the smiling expression of a sleeping child. I had his body sent back to Watervliet Arsenal, and there his gallant clay is lying. I have met men and soldiers of high rank and proud birth, but I do not believe I ever met Sergeant Harris's superior in the qualities that go to make a soldier and a man.

While engaged in this work the cry was started, "There it goes again!" On looking up I saw that the fire which had started on the wharf had just reached a small pile of ammunition, perhaps ten or fifteen boxes. Knowing, or at least thinking, that I could get to it before it could do any harm, I rushed in and with my army hat beat it out. The amusing part of this was, that an officer, a regular too by the way, was at my side when the cry was started, and when I had put out the fire and looked up, he was tearing up the bluff along with hundreds of others, all running as though they expected to be blown to atoms the next minute. All fear is ignorance ; I knew how the ammunition was packed; if I hadn't I should in all probability have been with the rest of them, and possibly in the lead.

The boat or barge, on the deck of which the torpedo was placed, had on board some twenty or thirty thousand rounds of artillery ammunition and in the vicinity of seventy-five or one hundred thousand rounds of small-arms ammunition. Between it and the wharf was a canal boat filled with cavalry saddles and equipments turned in by Sheridan's cavalry a few days before on embarking for Washington, which was then threatened by General Early. The explosion sent those old cavalry saddles flying in every direction like so many big-winged bats. One of them struck and killed the lemonade man, the only authorized vender of pop-syrups and lemonade at the depots. He had been with us some time, and was doing a thriving business under a tent-fly, surrounded by mule drivers, white and black, soldiers, civilians, and swarms of flies, when the saddle dashed through the crowd and hit him in the stomach. These details of his death were told me by Captain Randall, now General Randall, who was near by and saw the old saddle going through the crowd.

Among the flower beds of the garden behind my office one of my clerks fell, with a large piece of his skull torn off by the fuse of a shell that had burst over him. It was the most singular wound I ever saw, in this, that the substance of the brain apparently was not touched, but stood in place, a firm, white convoluted mass. We carried him back into the office from which he had fled when the projectiles that were hurled in every direction began to enter it.

While on these minor incidents, I may include that of the depot barber, a negro of the large, greasy, good-natured looking type. He joined us at Brandy Station, with an old and very dirty Sibley tent for a shop and an old and very dirty red plush chair, which he had brought out from Alexandria or Washington. He did a fine business with the teamsters. On this morning he had pitched his tent on the bluff near the tents of my colored employees, who, I'm inclined to think, kept him in rations and saw that he had transportation. We never saw anything of him or the chair after the explosion. I have sometimes wondered what was said and what became of that crowd and tent on the bluff. I imagine the barber was either shaving some one, in all probability a mule driver, who with eyes closed was in a blissful state of luxury, or he may have been cutting hair, or putting the last touches on to the lay of it with his brush, when he and his customer and "next " all went bowling out of, or remained wrapped up in, the old Sibley tent. That night, where it had stood lay twenty or thirty of my dead colored laborers in a row, for about dark a telegraph order came from Washington to report the names of all the dead. We gathered them together with the aid of a lantern, and then tried to check them off by the pay roll, but as we lifted one by one the coats or whatever covered their faces, to my surprise the foreman, a colored man by the name of Stephen from Baltimore, said, "I do not know him." The total number killed will never be known. Had the explosion occurred an hour earlier, just before the sailing of the Baltimore boat, when the wharf was crowded, the list of dead would have been of course much greater. There was a guard from some New York regiment detailed to keep all persons from going into the building or on board the boats. These were all killed. A musket was found standing upright in the road, buried to the second band, almost a half mile back from the wharf. I have always thought it must have been that of the sentinel on the deck of the barge, for it does not seem possible that any of the rifles in the storehouse could have attained a height such as this one must have reached to gain the necessary velocity to penetrate so deeply.

General Grant says somewhere in his Memoirs that "There are but few important events in the affairs of men brought about by their own choice." There were two striking incidents that morning differing widely in character, but both illustrating his truth. One was that of a Confederate who had been kept a prisoner at Headquarters for six or seven months, condemned to the Dry Tortugas, and who had been pardoned that morning, but who had reached the wharf too late for the boat. He then wandered about the depot, and we can imagine how light his heart was as he looked across the river to the rolling fields of his well-loved Virginia, thinking how soon he would reach his home, and of the welcome at the door. Some one saw him near the barge just before the explosion, and the next day his body was found three miles below City Point, drifting down the river. The other instance was that of a soldier of the Fourth Regulars, who was on guard on the river bank at the time of the explosion. Some of his comrades seeing the air filled with missiles told him to run and hide, but he refused to leave his post and fortunately escaped injury. This same man had been tried by court-martial some months previous and was sentenced to forfeit all his pay and allowance except one dollar per month during the remainder of his enlistment. A few days after the explosion he received notice that the fine was remitted for gallant conduct. Here were two examples — both, in the language of General Grant, "important events" in the lives of these two men — two men looking forward into the future with almost common experiences; both had been tried; both had been sentenced; both found their sentences revoked on the same day — but one of them drifted off down the James, and the other took his place with his colors and marched on with the rest to victory.

At first, in fact for months, I heard it said very often, that the explosion was the fault of "one of Schaff's niggers,"

who had let a percussion shell fall in his careless handling, but the true cause was not known till after the war was over, when there was found among the Confederate archives a drawing of the torpedo and the official report of the Confederate soldier, Captain Maxwell, who with great daring penetrated our lines with it."

The day was very hot, and knowing that my friend of the regulars was as dry as the rest of them that came down from the lines, I wished to show him the customary and most acceptable hospitality. I went to my demijohn and much to my surprise found it was empty. Evans must have looked especially despondent, for I said, "Come over to Grant's Headquarters; I know where I can get some," having in mind my friend Captain Mason of the 6th Regulars, who commanded Grant's escort. It was only a step, perhaps a hundred yards. When we reached the tent there we found ten or a dozen of Meade's and Grant's staff around a pail two-thirds full of claret punch. Among the rest was Captain, later Admiral, John Clitz of the United States Navy, one of the blithest hearted and most gallant men who ever trod a deck. His ship lay out in the river.

We had no sooner got there than Clitz, with whom I had had a very exciting game the day before, challenged me, and with Billy Worth (now General Worth, who was most severely wounded at Santiago) for his partner, and Captain Hudson of Grant's staff for mine, we began the game on Captain Mason's bed. I can't be certain how the game would have come out, but I had just captured two tens with a queen, which in all probability would have made the game at least, when the explosion took place and a 12-lb. solid shot crashed across the bed into Mason's camp mess-chest. Of course there was a sudden stampede. As there was something falling or shells bursting at every instant, I looked up to see what was coming next. The sky looked as it does in the fall of heavy snow flakes. Just then a shell burst immediately over us. In an instant we were all running for dear life. Clitz was the oldest and had complained of rheumatism while we were playing, in fact he had asked me to get him some more claret punch, declaring that it hurt him to walk; yet in the flight he was ahead of us all. Suddenly a piece of the shell came down over my left shoulder. I could have stepped on the hole it made in the ground, but it brought me to my senses, and I at once turned and made my way to the wharf.

From the top of the bluff there lay before me a staggering scene, a mass of overthrown buildings, their timbers tangled into almost impenetrable heaps. In the water were wrecked and sunken barges, while out among the shipping — where were many vessels of all sizes and kinds — there was hurrying back and forth on the decks to weigh anchor, for all seemed to think that something more would happen. I at once went down to the ruined building, a large frame structure six hundred feet long, under the charge of my Sergeant, Harris, an old regular and one of the gentlest and most faithful and honest men I ever knew. I could hear the cries of some of the men, and soon heard Corporal Bradley call out, "For God's sake, Captain, come and help me out." He was pinned down under some heavy timbers with one of his legs crushed. It was amputated, and I saw him after the war at West Troy, New York. Later, I found Sergeant Harris lying on his back dead, with the smiling expression of a sleeping child. I had his body sent back to Watervliet Arsenal, and there his gallant clay is lying. I have met men and soldiers of high rank and proud birth, but I do not believe I ever met Sergeant Harris's superior in the qualities that go to make a soldier and a man.

While engaged in this work the cry was started, "There it goes again!" On looking up I saw that the fire which had started on the wharf had just reached a small pile of ammunition, perhaps ten or fifteen boxes. Knowing, or at least thinking, that I could get to it before it could do any harm, I rushed in and with my army hat beat it out. The amusing part of this was, that an officer, a regular too by the way, was at my side when the cry was started, and when I had put out the fire and looked up, he was tearing up the bluff along with hundreds of others, all running as though they expected to be blown to atoms the next minute. All fear is ignorance ; I knew how the ammunition was packed; if I hadn't I should in all probability have been with the rest of them, and possibly in the lead.

The boat or barge, on the deck of which the torpedo was placed, had on board some twenty or thirty thousand rounds of artillery ammunition and in the vicinity of seventy-five or one hundred thousand rounds of small-arms ammunition. Between it and the wharf was a canal boat filled with cavalry saddles and equipments turned in by Sheridan's cavalry a few days before on embarking for Washington, which was then threatened by General Early. The explosion sent those old cavalry saddles flying in every direction like so many big-winged bats. One of them struck and killed the lemonade man, the only authorized vender of pop-syrups and lemonade at the depots. He had been with us some time, and was doing a thriving business under a tent-fly, surrounded by mule drivers, white and black, soldiers, civilians, and swarms of flies, when the saddle dashed through the crowd and hit him in the stomach. These details of his death were told me by Captain Randall, now General Randall, who was near by and saw the old saddle going through the crowd.

Among the flower beds of the garden behind my office one of my clerks fell, with a large piece of his skull torn off by the fuse of a shell that had burst over him. It was the most singular wound I ever saw, in this, that the substance of the brain apparently was not touched, but stood in place, a firm, white convoluted mass. We carried him back into the office from which he had fled when the projectiles that were hurled in every direction began to enter it.

While on these minor incidents, I may include that of the depot barber, a negro of the large, greasy, good-natured looking type. He joined us at Brandy Station, with an old and very dirty Sibley tent for a shop and an old and very dirty red plush chair, which he had brought out from Alexandria or Washington. He did a fine business with the teamsters. On this morning he had pitched his tent on the bluff near the tents of my colored employees, who, I'm inclined to think, kept him in rations and saw that he had transportation. We never saw anything of him or the chair after the explosion. I have sometimes wondered what was said and what became of that crowd and tent on the bluff. I imagine the barber was either shaving some one, in all probability a mule driver, who with eyes closed was in a blissful state of luxury, or he may have been cutting hair, or putting the last touches on to the lay of it with his brush, when he and his customer and "next " all went bowling out of, or remained wrapped up in, the old Sibley tent. That night, where it had stood lay twenty or thirty of my dead colored laborers in a row, for about dark a telegraph order came from Washington to report the names of all the dead. We gathered them together with the aid of a lantern, and then tried to check them off by the pay roll, but as we lifted one by one the coats or whatever covered their faces, to my surprise the foreman, a colored man by the name of Stephen from Baltimore, said, "I do not know him." The total number killed will never be known. Had the explosion occurred an hour earlier, just before the sailing of the Baltimore boat, when the wharf was crowded, the list of dead would have been of course much greater. There was a guard from some New York regiment detailed to keep all persons from going into the building or on board the boats. These were all killed. A musket was found standing upright in the road, buried to the second band, almost a half mile back from the wharf. I have always thought it must have been that of the sentinel on the deck of the barge, for it does not seem possible that any of the rifles in the storehouse could have attained a height such as this one must have reached to gain the necessary velocity to penetrate so deeply.

General Grant says somewhere in his Memoirs that "There are but few important events in the affairs of men brought about by their own choice." There were two striking incidents that morning differing widely in character, but both illustrating his truth. One was that of a Confederate who had been kept a prisoner at Headquarters for six or seven months, condemned to the Dry Tortugas, and who had been pardoned that morning, but who had reached the wharf too late for the boat. He then wandered about the depot, and we can imagine how light his heart was as he looked across the river to the rolling fields of his well-loved Virginia, thinking how soon he would reach his home, and of the welcome at the door. Some one saw him near the barge just before the explosion, and the next day his body was found three miles below City Point, drifting down the river. The other instance was that of a soldier of the Fourth Regulars, who was on guard on the river bank at the time of the explosion. Some of his comrades seeing the air filled with missiles told him to run and hide, but he refused to leave his post and fortunately escaped injury. This same man had been tried by court-martial some months previous and was sentenced to forfeit all his pay and allowance except one dollar per month during the remainder of his enlistment. A few days after the explosion he received notice that the fine was remitted for gallant conduct. Here were two examples — both, in the language of General Grant, "important events" in the lives of these two men — two men looking forward into the future with almost common experiences; both had been tried; both had been sentenced; both found their sentences revoked on the same day — but one of them drifted off down the James, and the other took his place with his colors and marched on with the rest to victory.

At first, in fact for months, I heard it said very often, that the explosion was the fault of "one of Schaff's niggers,"

who had let a percussion shell fall in his careless handling, but the true cause was not known till after the war was over, when there was found among the Confederate archives a drawing of the torpedo and the official report of the Confederate soldier, Captain Maxwell, who with great daring penetrated our lines with it."