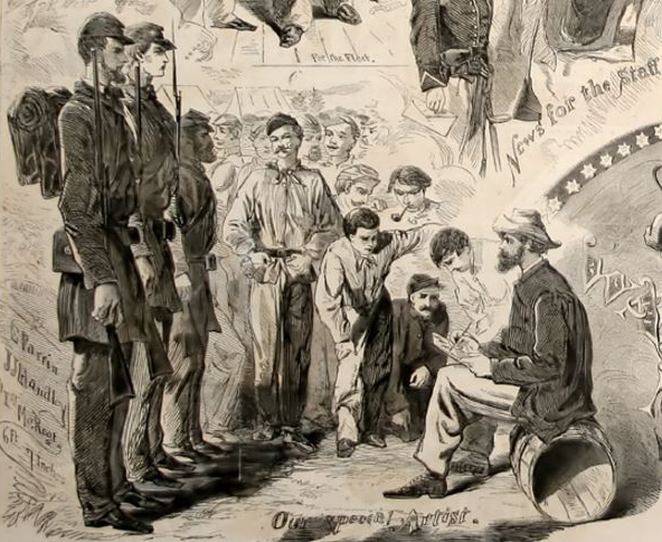

Winslow Homer, Special Artist for Harper's Weekly

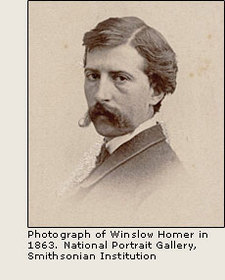

Winslow Homer was born in Boston in 1836 to a family with a long line of New Englanders on both sides. First taught by his mother, Homer had established a career as a commercial illustrator by the time the Civil War began. Harper’s Weekly sent him to the front at the beginning of the war where he sketched scenes while with the Army of the Potomac. He began painting war scenes in oil based on his sketches. Beginning with this work and until his death in 1910, Homer created prints and paintings that make him a preeminent figure in American art.

This post focuses on sketches Homer is known to have done, or likely did, during two wartime trips to the Petersburg front- in June 1864 and March 1865- and the paintings that resulted from the sketches. The paintings include two of Homer's most iconic works- Prisoners from the Front and Defiance. By this point, three years into the bloodiest war in American history, Homer drops out of sight from the pages of Harper's Weekly. It isn't known whether or not it was his decision to step back from the Special Artist role or that of the publication, but the result was paintings that speak powerfully, to to this day, of the conflicts and desolation of war. Unlike the other Special Artists whose drawings we pore over on this site to ascertain specific details about battles, fortifications, and terrain, we turn to Homer for deeper insight.

This post focuses on sketches Homer is known to have done, or likely did, during two wartime trips to the Petersburg front- in June 1864 and March 1865- and the paintings that resulted from the sketches. The paintings include two of Homer's most iconic works- Prisoners from the Front and Defiance. By this point, three years into the bloodiest war in American history, Homer drops out of sight from the pages of Harper's Weekly. It isn't known whether or not it was his decision to step back from the Special Artist role or that of the publication, but the result was paintings that speak powerfully, to to this day, of the conflicts and desolation of war. Unlike the other Special Artists whose drawings we pore over on this site to ascertain specific details about battles, fortifications, and terrain, we turn to Homer for deeper insight.

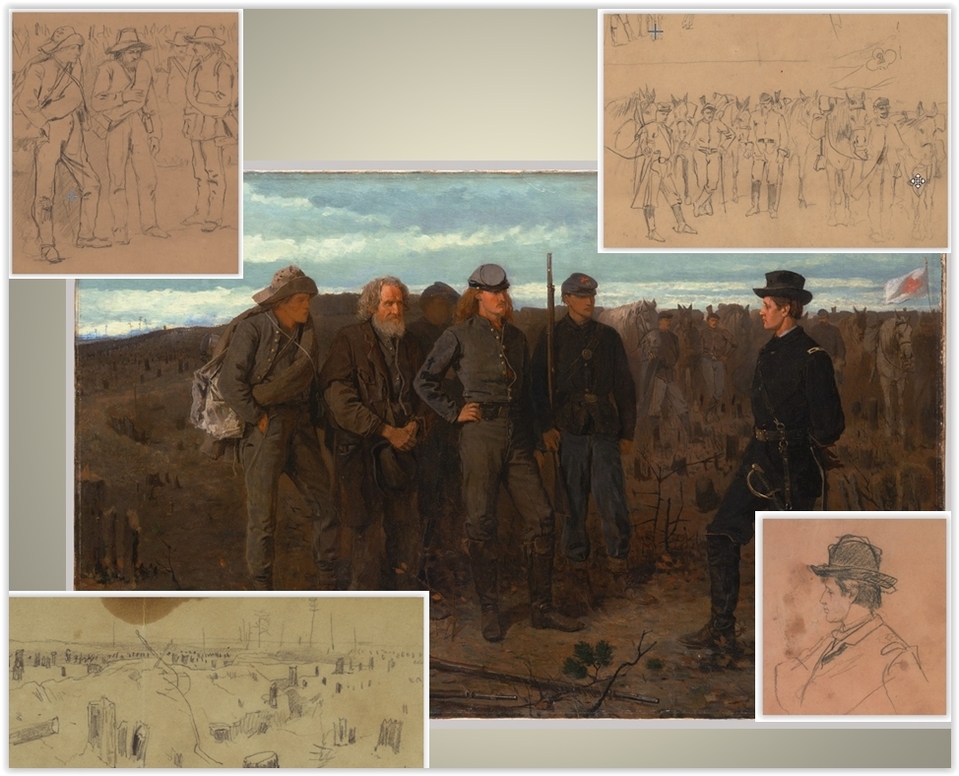

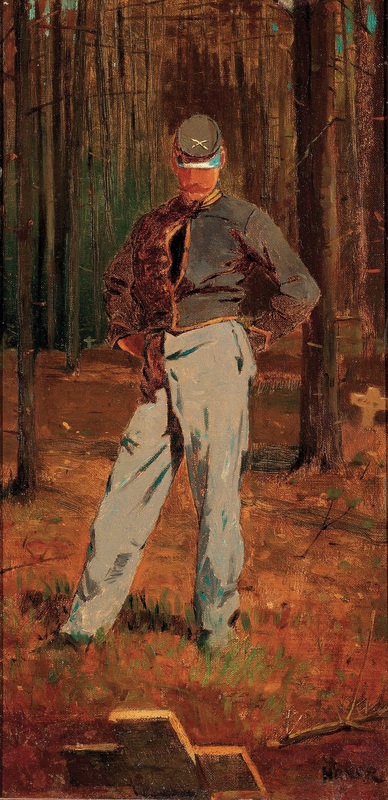

Prisoners From the Front. 1866. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

According to the catalog entry, "The material that Homer collected as an artist-correspondent during the Civil War provided the subjects for his first oil paintings. In 1866, one year after the war ended and four years after he reputedly began to paint in oil, Homer completed this picture, a work that established his reputation. It represents an actual scene from the war in which a Union officer, Brigadier General Francis Channing Barlow (1834–1896) captured several Confederate officers on June 21, 1864. The background depicts the battlefield at Petersburg, Virginia. Infrared photography and numerous studies indicate that the painting underwent many changes in the course of completion."

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/11133?ft=Winslow+Homer&pg=1&rpp=20&pos=1

Homer is known to have associated with Barlow earlier in the war and may have continued to do so during the Petersburg Campaign in 1864-1865. This association is not surprising: Homer was Barlow's cousin and his brother Charles was at Harvard with Barlow. The only known documentation of Homer's activities during this time comes from his art.

Elizabeth Johns, Winslow Homer: The Nature of Observation, University of California Press, 2001:44-45.

Christian Samito, Fear Was Not In Him: the Civil War Letters of Major General Francis C. Barlow, Fordham University Press, 2004:48.

http://www.civilwar.si.edu/homer_intro.html

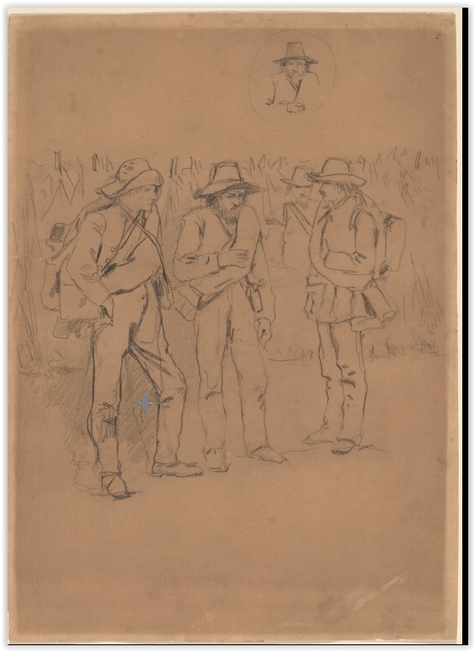

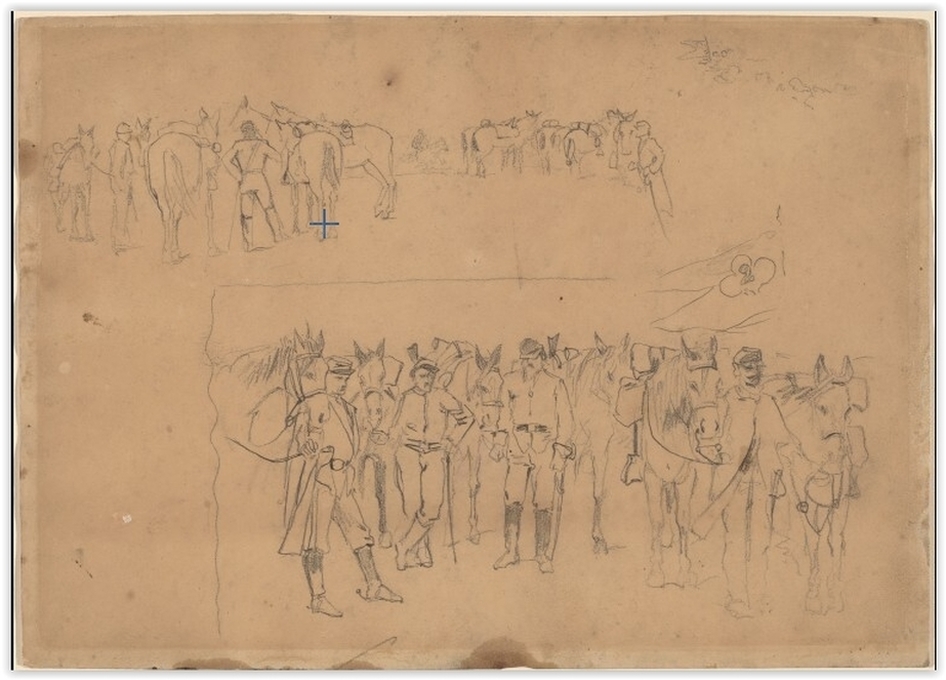

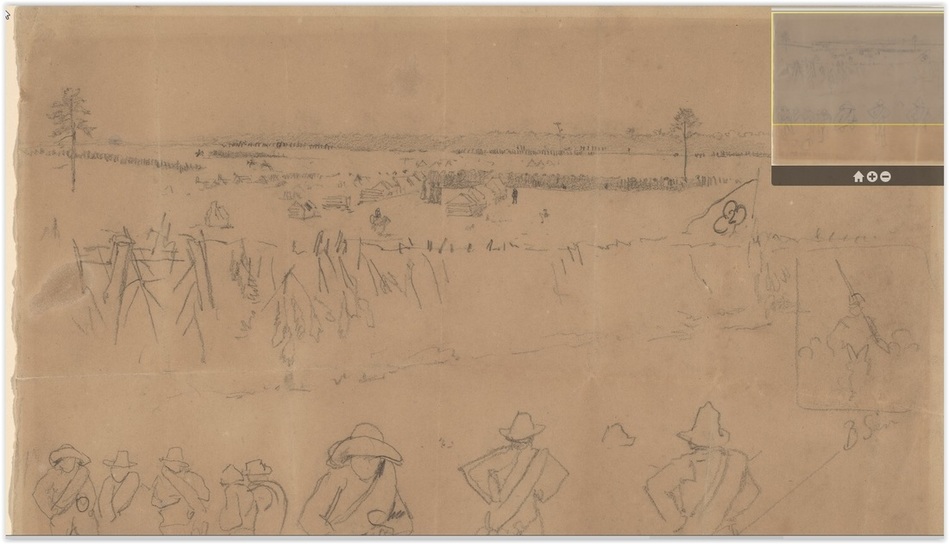

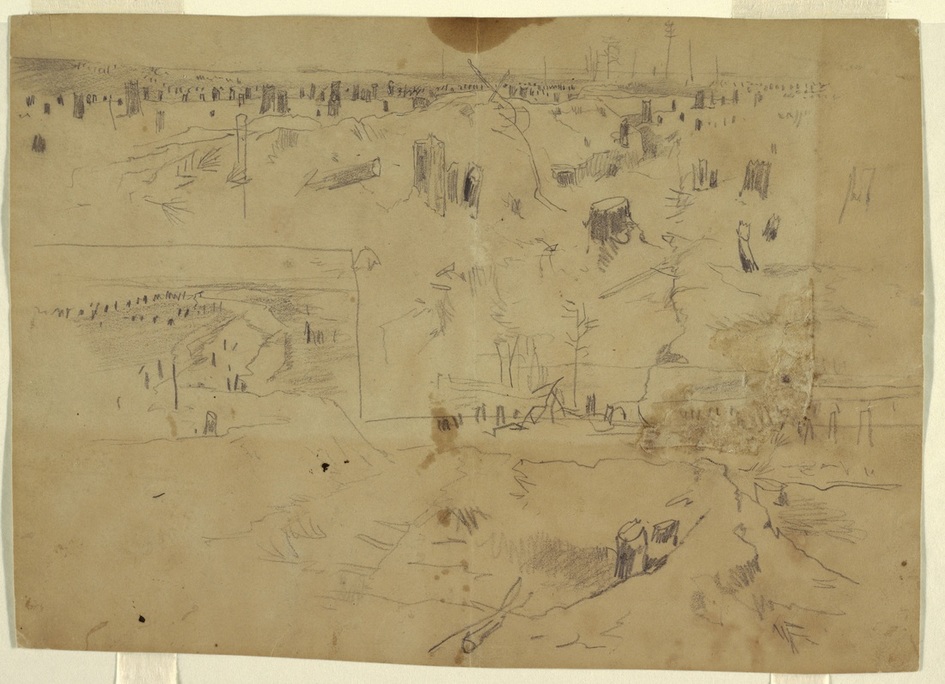

Homer used sketches drawn in the field to compose Prisoners From the Front. The top overlays added on to the painting below are from a war-time sketchbook held at the National Gallery of Art. The two on the bottom are from another notebook held at the Cooper Hewitt Museum. The Cooper Hewitt sketches were done on the two sides of a single piece of paper: the side with the drawing of slashed trees is clearly labeled "Petersburg". The other two drawings are dated 1864 so are also likely to have been drawn at Petersburg where the Federal campaign to capture the city began in June. Barlow and the First Division of the Second Corps of the Army of the Potomac were in action against Confederate forces at the Jerusalem Plank Road on June 21, 1864, and Homer may have observed Confederate prisoners being taken to the rear at that time. No sketch has been found that depicts the entire scene as shown in the painting, but the finished painting is compiled of faithful copies of sketches and portions of sketches with new elements added to complete the scene.

Additionally, the drawings, however accurate and done on the spot, do not reflect the actual scene in that they lack one real world element- color. Homer's black line drawings were adequate for reporting as a special artist for Harper's Weekly, but color added a whole new layer of emotional impact to the paintings. The landscape in Prisoners at the Front is sere and wintery, except for the one evergreen sprig in the foreground. Contemporary accounts describe a dry, dusty, relatively waterless landscape around Petersburg in June, 1864, but nonetheless, it was early summer and fields and woods were alive with growth. The siege was just beginning, and the impact of the armies would not have halted this natural process in so short a period of time. Many accounts of the early battles and siege operations mention wheat, oat and corn fields as well orchards. The exception to this early summer growth lay in the acres and acres of "slashings"- locations where the Confederate defenders of the town had downed trees to open fields of fire in front of their defensive works. These slashings also served as difficult obstacles for the enemy to work through. The only bright colors in Prisoners From The Front are the red trefoil on the U.S. II Corps flag, the red insignia on the U.S. soldiers' caps, and the aforementioned evergreen needles. The ravaged, subdued and colorless landscape is more like what Homer would have experienced on his second trip to the Petersburg front in late winter, early spring, 1865, than during his first trip in June, 1864. His conflated experiences serve to make the work more powerful.

Homer used at least four identified sketches to compose the elements in his famous painting "Prisoners from the Front."

One of the gray horses pictured above may be the mount described below:

"A Confederate colonel was captured during the fight [Jerusalem Plank Road]. He was mounted on a superb gray horse which General Barlow afterwards purchased and rode in battle. The splendid animal became very fond of the General and would follow him around the camp begging for the lumps of sugar that the General would be pretty sure to have in his pocket with which to treat his equine friend".

St. Clair A. Mulholland, The Story of the 116th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, p.278.

"A Confederate colonel was captured during the fight [Jerusalem Plank Road]. He was mounted on a superb gray horse which General Barlow afterwards purchased and rode in battle. The splendid animal became very fond of the General and would follow him around the camp begging for the lumps of sugar that the General would be pretty sure to have in his pocket with which to treat his equine friend".

St. Clair A. Mulholland, The Story of the 116th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, p.278.

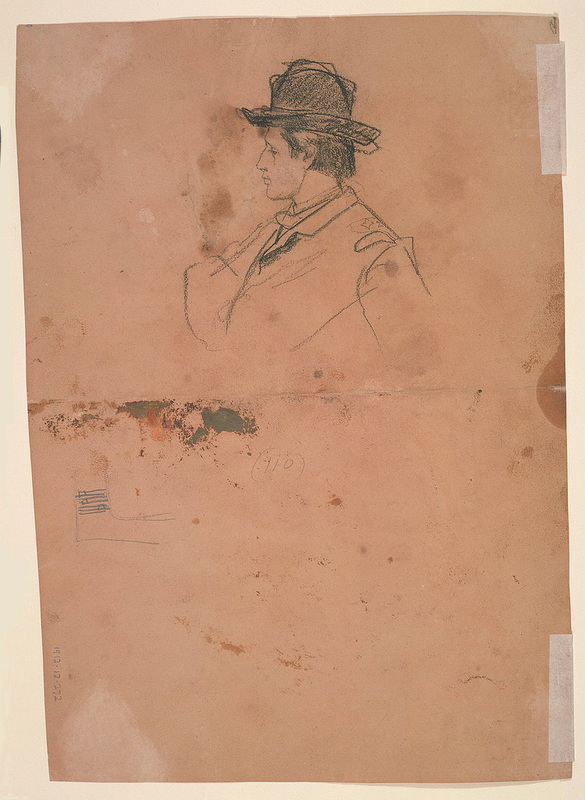

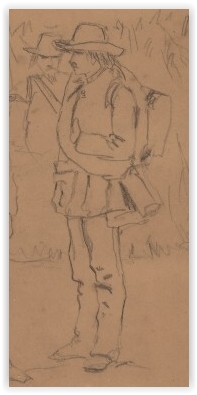

The drawing above on the left, from the National Gallery of Art, is titled Prisoners of War,1864. The soldier on the far left of the group is faithfully depicted in the painting Prisoners From the Front, while the others were modified, perhaps based on other sketches. The drawing on the right is cataloged as an unknown officer at the Cooper Hewitt Museum, but it is almost certainly a sketch of Francis Channing Barlow. Compare this sketch with Barlow's photo below. His boyish looks were often commented upon, sometimes contrasted with his hard sense of discipline in the ranks.

When he had nearly finished his picture, Homer painted out the head of the person who had posed for the general and replaced it with a picture of his cousin,Francis Barlow.

|

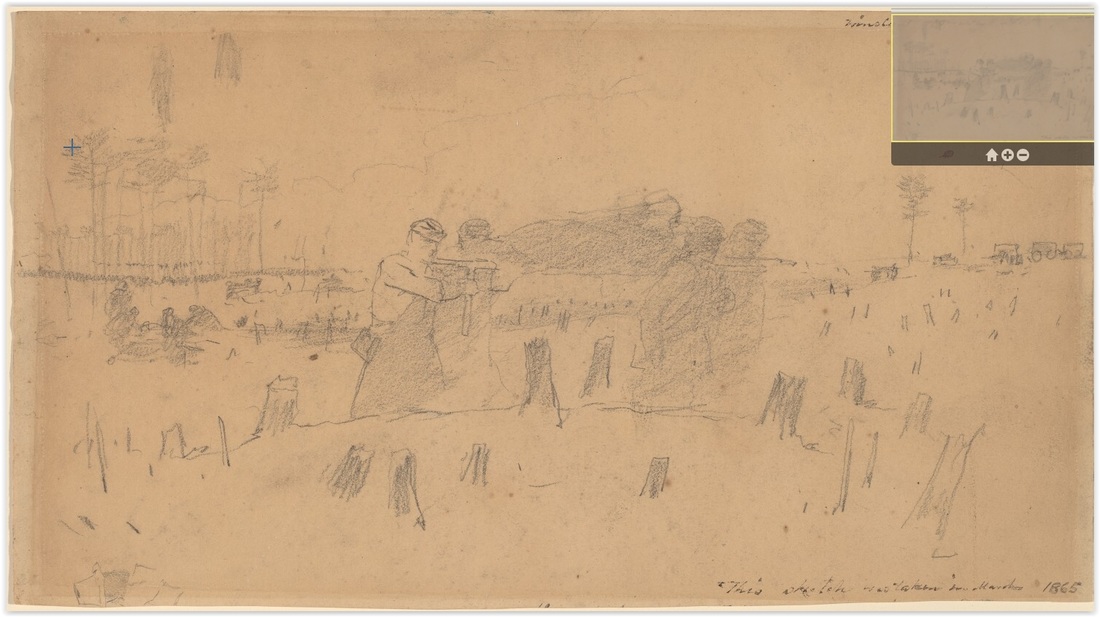

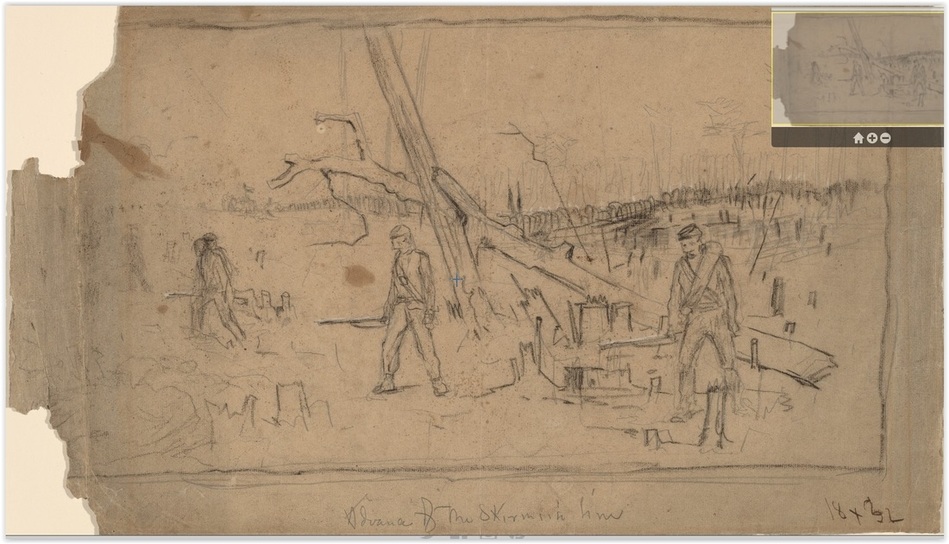

Drawing, "Studies of a Battlefield with Tree Stumps and Blasted Tree Trunks, Petersburg, Virginia. 1864." Cooper Hewitt Museum. Details of the felled trees, known as slashing, and damaged trees on the horizon can be seen in the oil painting above. This drawing also seems to have been used in his 1864 painting Defiance, below.

Advance of the Skirmish Line. 1864. National Gallery of Art.

Advance of the Skirmish Line. 1864. National Gallery of Art.

It would have been difficult for Homer to cross to the Confederate side of the lines, but he was on the Federal side of the field and conditions were similar on both sides. Once again, as with Prisoners From the Front, Homer aspires to emotional truth, rather than the reportorial accuracy required from the newspaper Special Artist. In reaching for emotional truth, he uses drawings made at the front, but melds them into powerful statements about conflict and its aftermath. Defiance draws heavily on the sketch titled Studies of a Battlefield with Tree Stumps and Blasted Tree Trunks, Petersburg, Virginia,1864, at the Cooper Hewitt Museum, reproduced above- even down to the bare branch in the forefront and the earthwork snaking towards the horizon. Homer was fascinated by the desolation wrought by the cutting of trees to clear fields of fire, provide obstacles, and use for construction of fortifications and camps. There is some green vegetal life in the hills to the left of the painting and behind the line to the right, but the foreground, trailing into the distance, consists of dull, raw earth. During the Victorian period, gravestones depicting slashed tree trunks, or broken tree trunks and branches, symbolized a life cut short. It seems likely that Homer's obsession with stumps, leafless branches, and standing trees blighted by artillery fire, along with the gray skies and desolate landscapes he painted at Petersburg, exemplifies the thousands of lives blighted and cut short by war.

The spindly trees on the horizon in both famous Petersburg paintings are also reminiscent of the breaking wheels pictured in many medieval paintings (for example, The Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel the Elder). These devices, tall poles crowned by wooden wheels, were both torture for the living and post-mortem punishment for the dead. Life in the trenches at Petersburg was painted in words by the names Fort Damnation and Fort Hell, given to two opposing fortifications- both miserable.

(c) The Petersburg Project 2017

The spindly trees on the horizon in both famous Petersburg paintings are also reminiscent of the breaking wheels pictured in many medieval paintings (for example, The Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel the Elder). These devices, tall poles crowned by wooden wheels, were both torture for the living and post-mortem punishment for the dead. Life in the trenches at Petersburg was painted in words by the names Fort Damnation and Fort Hell, given to two opposing fortifications- both miserable.

(c) The Petersburg Project 2017