The Petersburg Project is a volunteer effort by two historians and an archeologist to understand the origins and nature of trench warfare in the last year of the Civil War. Understanding trench warfare requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes both traditional history and archeology. Since so much of what Civil War soldiers accomplished in the final year of the war was never described in manuals and barely documented in personal accounts, it is essential to study not only the textual records, but also photographs, maps and the archeological record.

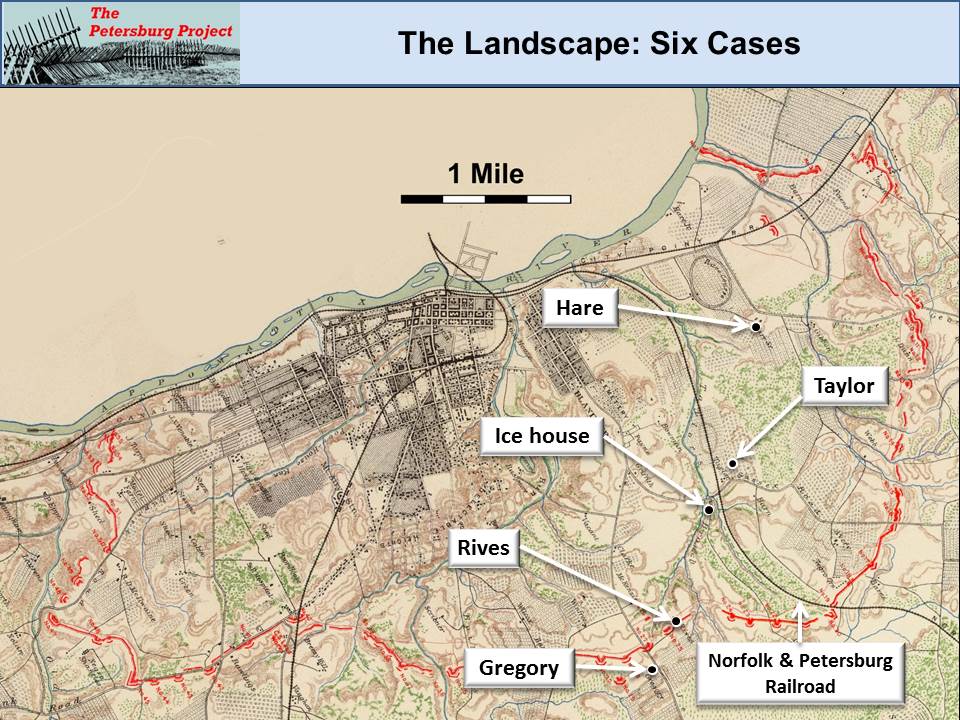

This paper, originally presented as a Powerpoint presentation at the annual meeting of the Council for Northeast Historical Archaeology in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in November 2015, will demonstrate some of the ways we are using archeological approaches to better understand the impact of the siege on the landscape and conversely the impact of the landscape on the siege. We will look at six structures, four houses, an ice house and a railroad, and describe how they fared during nine and half months of intense prolonged conflict.

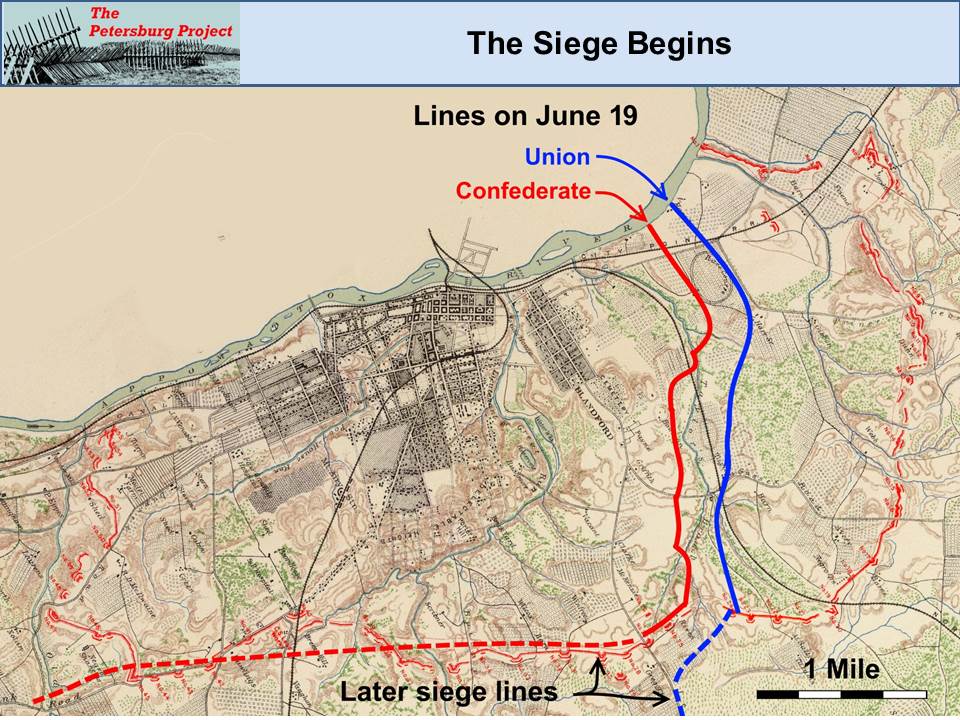

These structures were all located on or near the siege lines which were established on June 18, 1864. June 18th was the fourth day of an assault that brought the Federal Army of the Potomac and a portion of the Army of the James from north of the James River in a surprise movement against Confederate forces under General P. G. T. Beauregard. The Confederates defended the city from the Dimmock Line, a ring of fortifications that encircled the city south of the Appomattox River. Beauregard’s vastly outnumbered forces fought tenaciously, but by the third day of fighting, they were rolled back to a second line of hastily constructed defenses on the eastern side of the city. When Union forces pressed forward on the foggy, dusty morning of June 18th, they found their opponents had fallen back to yet a third defensive line almost a mile closer to the city. Nonetheless, Confederate skirmishers, sharpshooters, and artillery, skillfully held back the enemy as their comrades completed their new line of fortifications. The defenders used the natural ravines and woods and man-made obstacles, such as the cut road bed of the Norfolk-Petersburg Railroad, to their advantage in stopping the foe. The Confederate defense of Petersburg against the approach of the Army of the Potomac in June 1864 represents one of the finest defensive fights of the Civil War. As a general, it was Beauregard's finest moment in history.

By the end of the day on June 18th, Federal troops had dug in as close as 90 yards from the Confederate line in several locations. Meanwhile, General Robert E. Lee had awakened to the dire threat against his southern flank. He issued orders that dispatched tens of thousands of reinforcements from the Army of Northern Virginia to the threatened Petersburg front to save the city and its vital industries and transportation network. The line taken up on the 18th was to be held the Confederates for the next nine and a half months of grinding trench warfare, punctuated by sharp battles as Federal forces attempted to break through or flank the Confederate defenses, which grew in strength with every passing day.

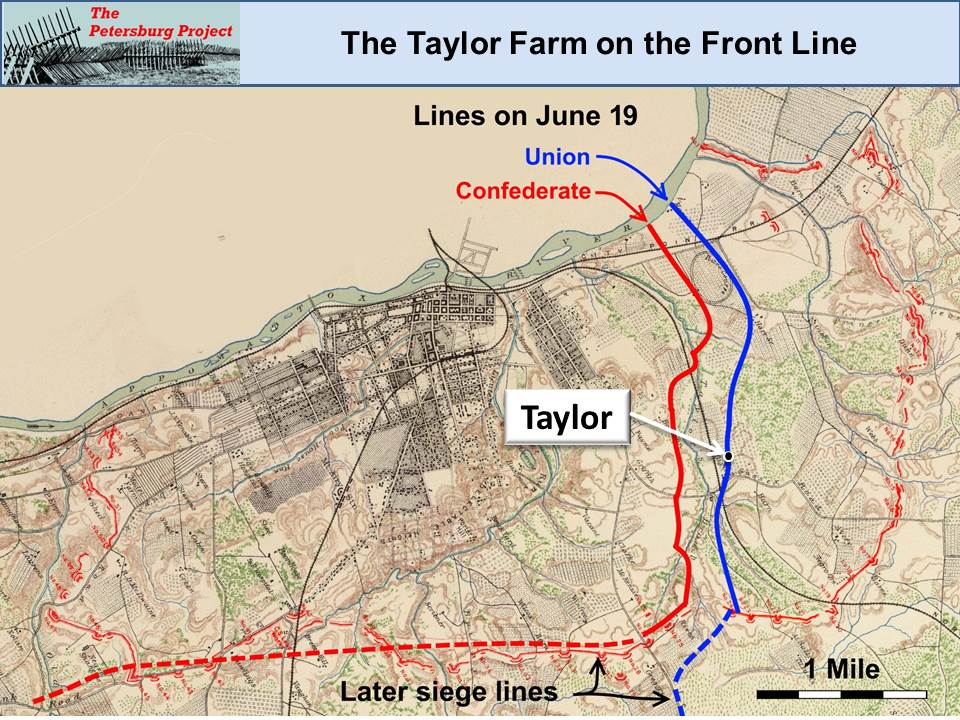

During the opening Union assaults, Confederate General Bushrod Johnson established his headquarters at the Taylor house, or Spring Garden plantation, located east of Petersburg. Taylor House By the morning of June 18th, Johnson and the other Confederate commanders had pulled their troops west across the Norfolk & Petersburg railroad, which snaked its way across the battlefield. From there, Johnson wrote, they watched the “The enemy’s line, about one brigade of Yankees about [the] crest of [the]hill [on the] east side of Taylor’s Creek in front of Taylor’s house….” (Supplement to the OR: 277). The battle swirled around the Taylor estate that day, and afterwards the Federals built their main siege line upon it, including a massive bastion known as Fort Morton.

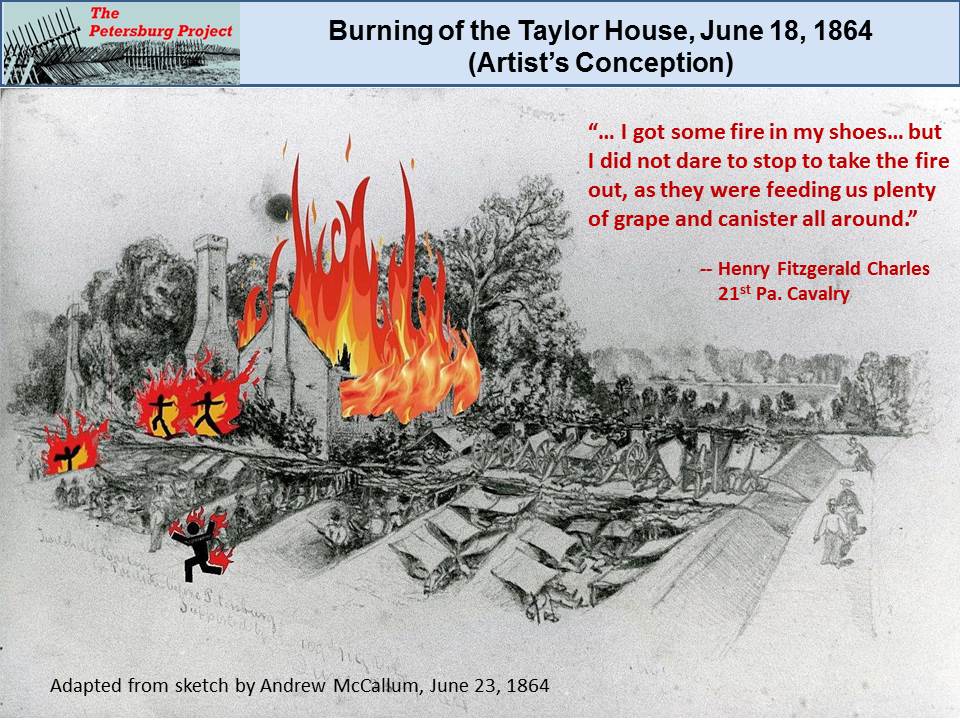

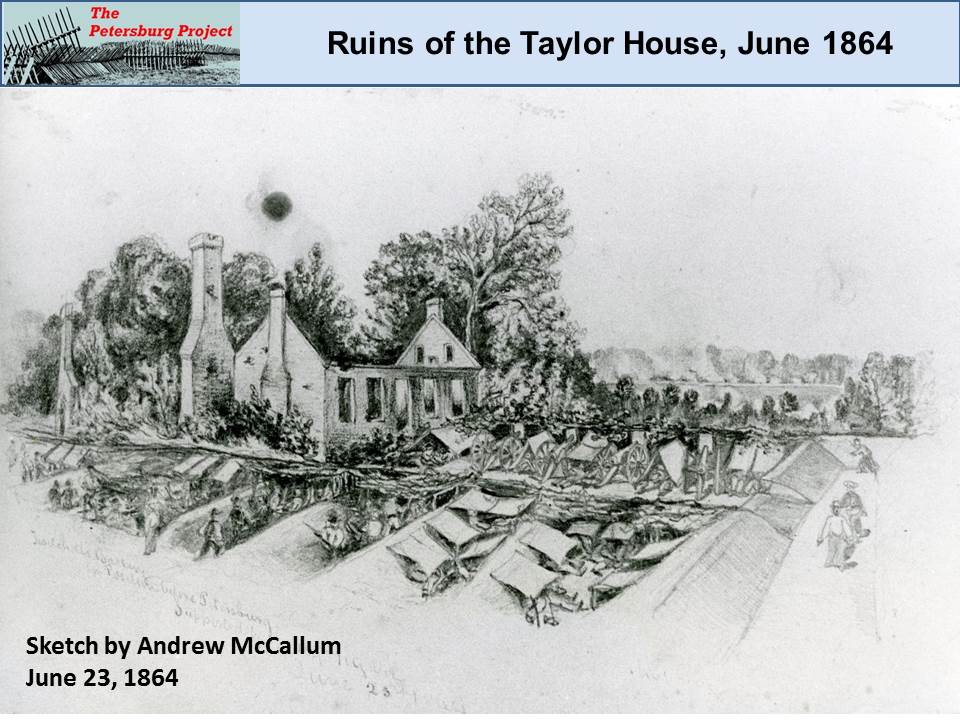

The destruction of the house and its outbuildings began on June 18th. The approaching Unionists found it in flames. Henry Fitzgerald Charles of the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry noted, “We started and took the [railroad] cut, but while going down, some of us had to go thru where some buildings were burned down. There was still plenty of fire and hot ashes, and I got some fire in my shoes. My one foot was burned considerable, but I did not dare to stop and take the fire out, as they were feeding us plenty of grape and canister all around” (Charles, n.d.).

This sketch, drawn by a Union soldier five days into the siege, shows partially destroyed buildings at the Taylor farm, with Union artillery and infantry arrayed around them. During subsequent weeks the combatants often referred to the “burnt house”, the “wall of the old brick house”, and, more starkly, “chimneys”.

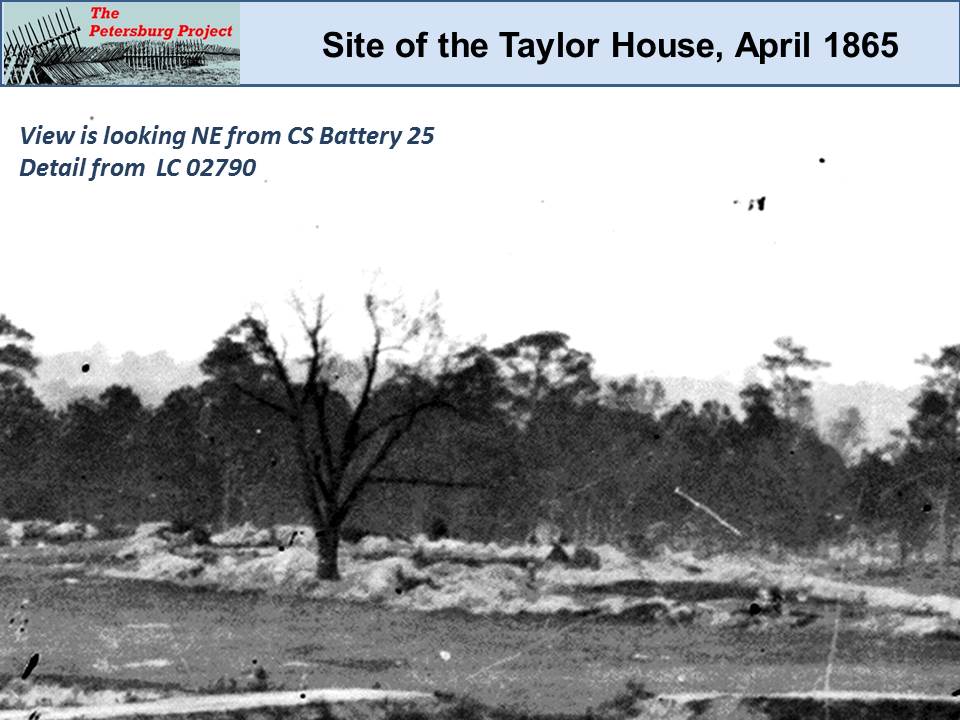

Over the next few months even those ruins disappeared as the soldiers scavenged them for building materials. By 1865 nothing remained of the house site but an old oak tree, a well and mounds of dirt.

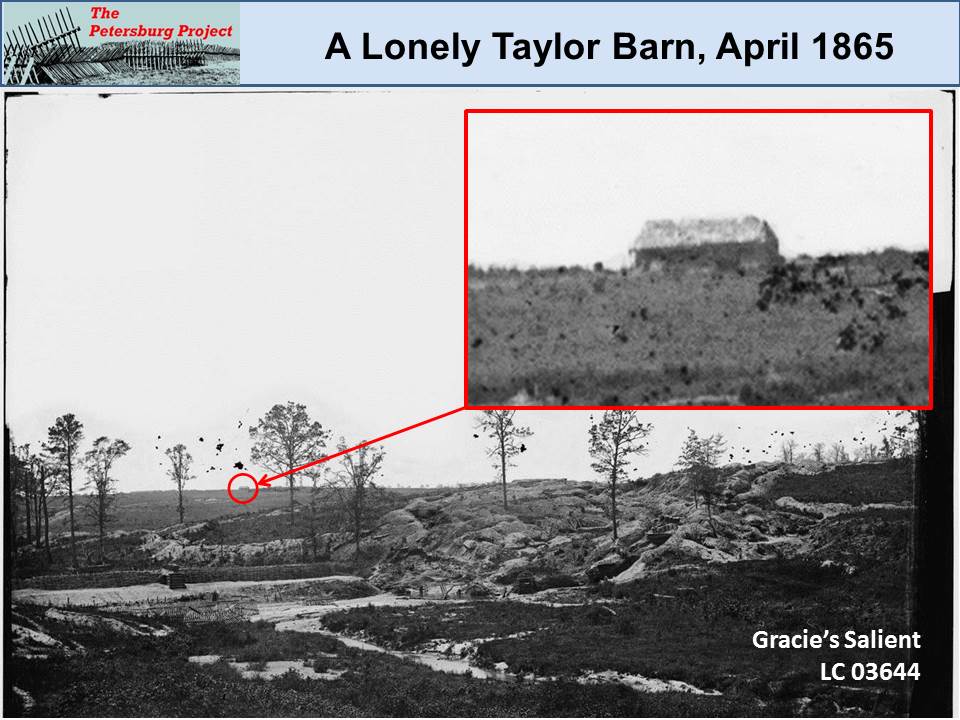

Photographs taken after the end of the siege in April 1865 reveal but a single structure remaining, apparently a ruined barn on a hilltop.

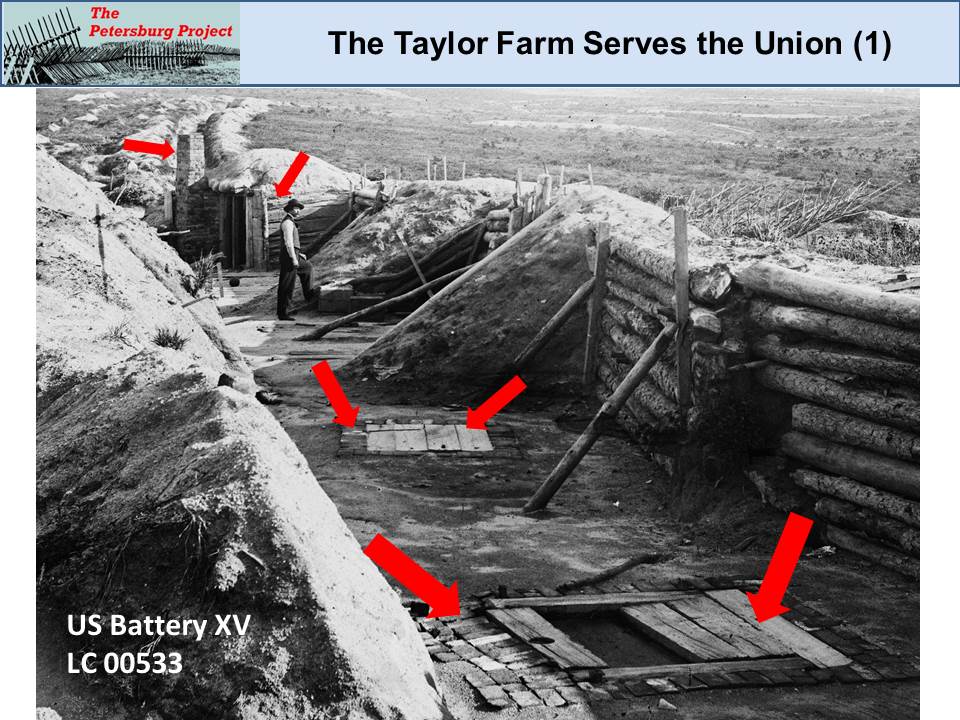

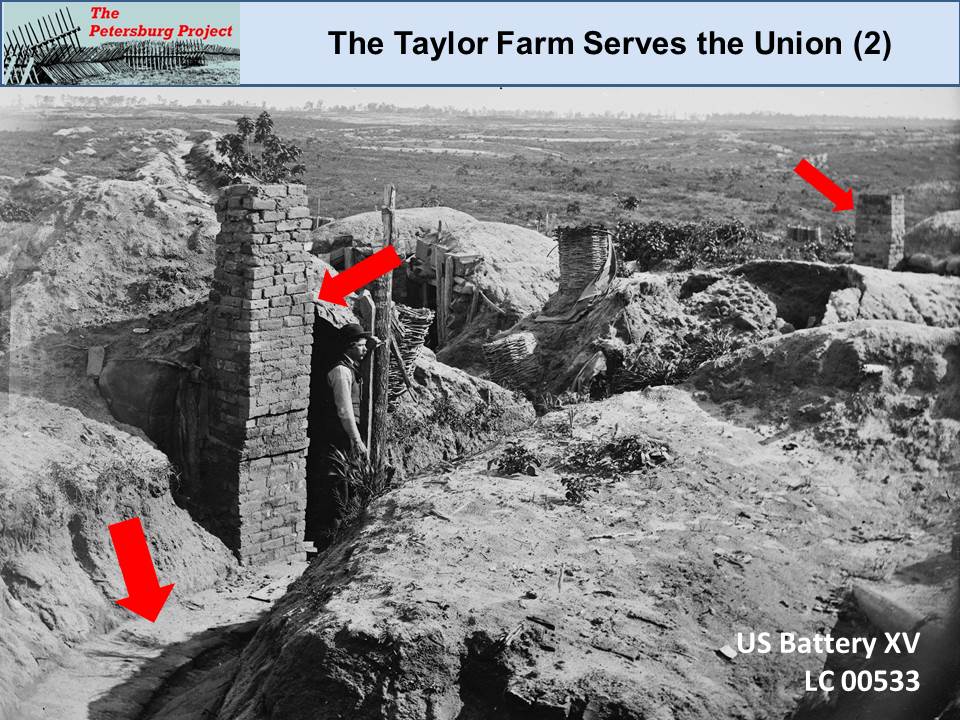

However, the Taylor buildings may have disappeared, but the materials in them did not. Photographs show scavenged building materials incorporated into the Federal defensive works and fortified habitations.

This photograph of Union Battery XV shows how Taylor’s bricks and lumber were used to build platforms for the mortars that sent shells arcing high over the enemy’s trenches, and for the bombproof shelters that protected the men from return fire.

This image was taken nearby, a few feet behind Battery XV. Note that bricks have been used for chimneys and lumber for paving the trench.

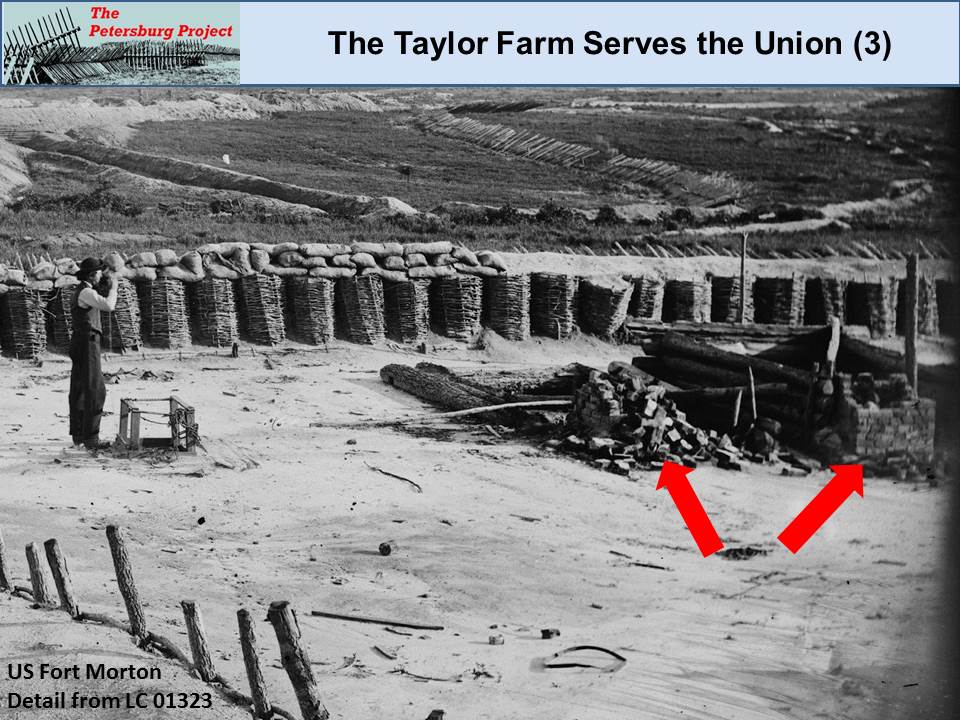

The troops manning Fort Morton built partial log structures with brick hearths, which appear to have been damaged by enemy shell-fire.

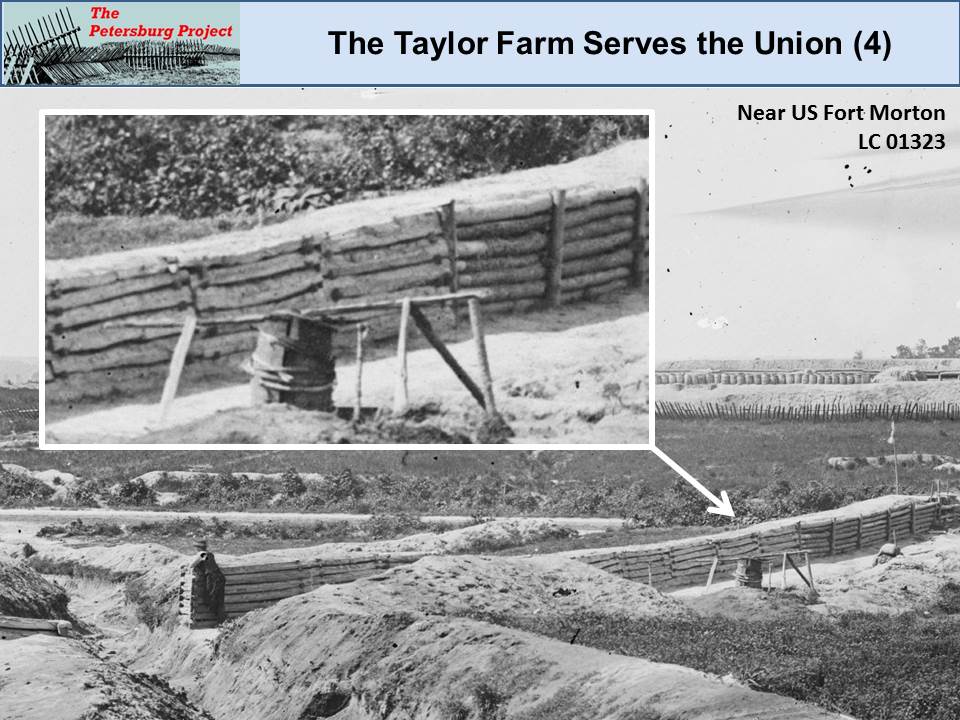

This infantry line just south of Fort Morton was likely constructed from a squared log outbuilding. The more typical bark-on round log revetment is next to it.

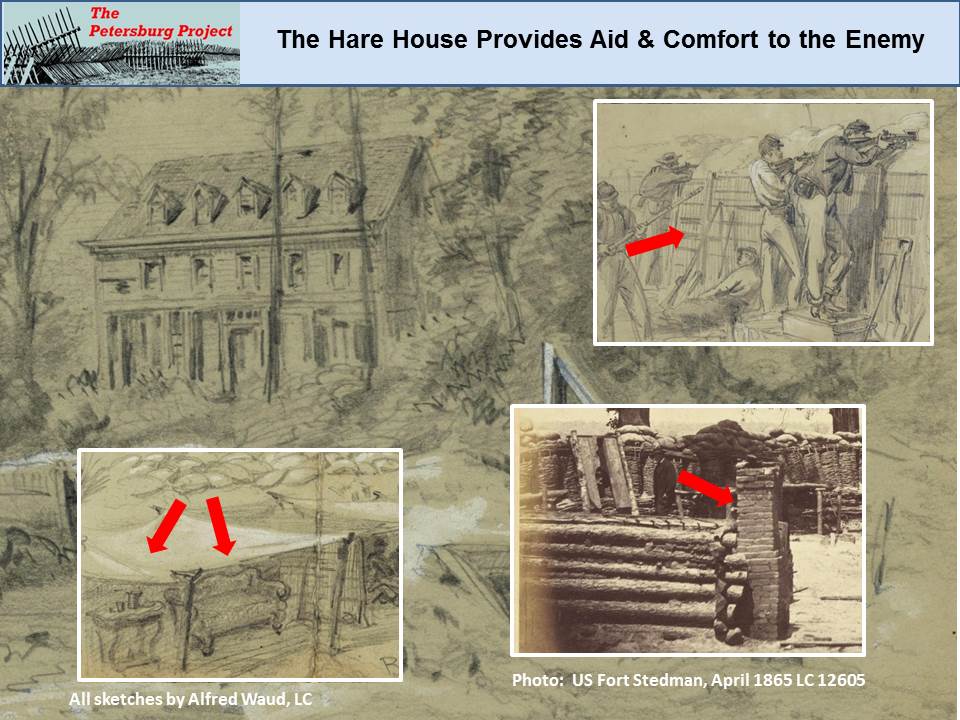

About a mile to the north, Taylor’s neighbor Otway P. Hare, also lost his home which stood near the future site of Federal Fort Stedman. The Federals stripped it of lumber, bricks and even furniture to make themselves comfortable in their trenches. Hare House

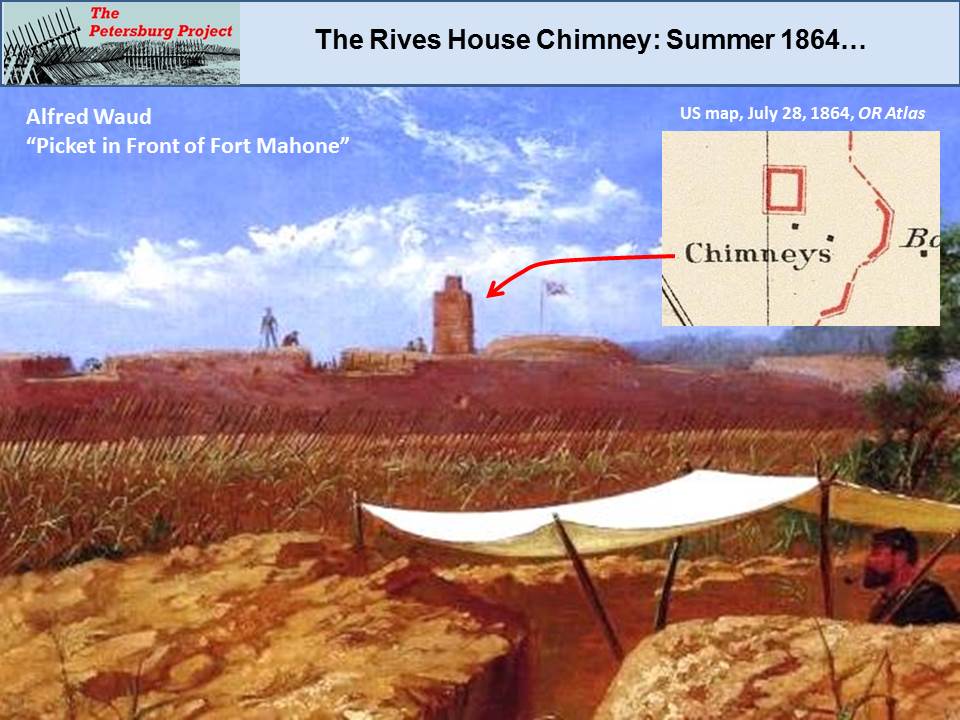

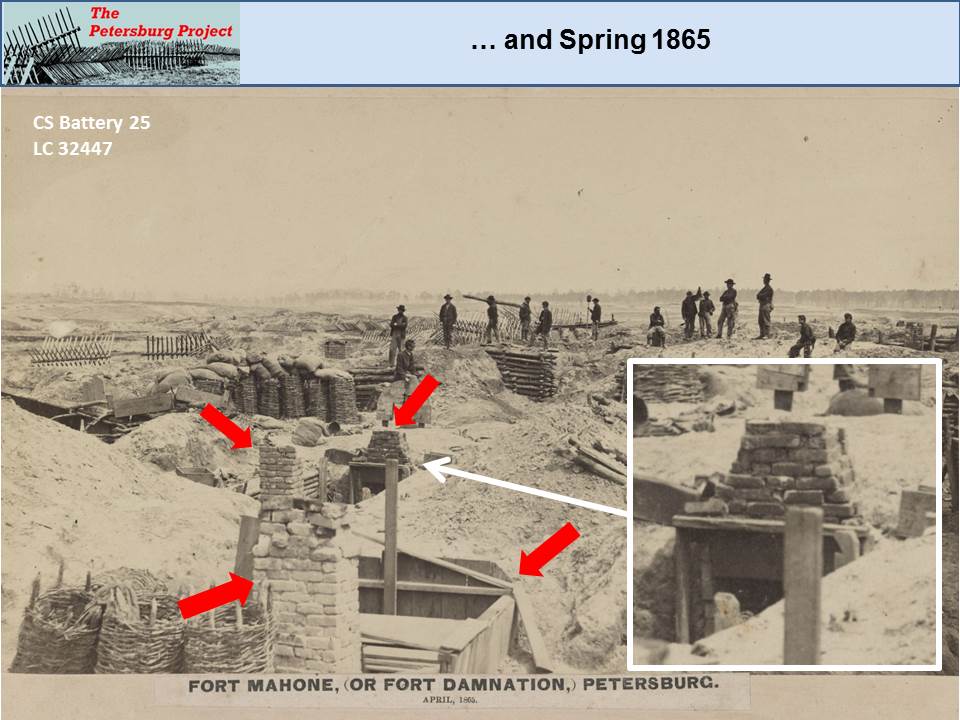

The Confederates did the same. Like many buildings along the lines, the Rives house was just a chimney soon after the siege began….

And by the following spring, its bricks and planking were used for soldier huts and chimneys.

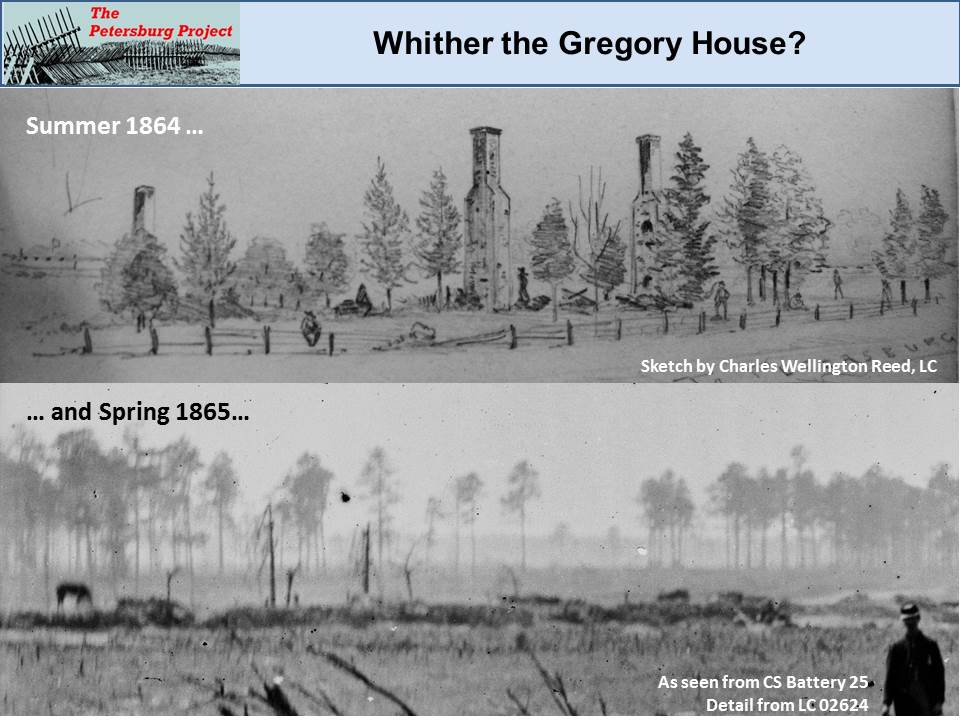

The Gregory House, which stood on the Confederate picket line on Jerusalem Plank Road, suffered the same fate. A sketch created early in the summer of 1864 shows only chimneys. By 1865, those were gone too.

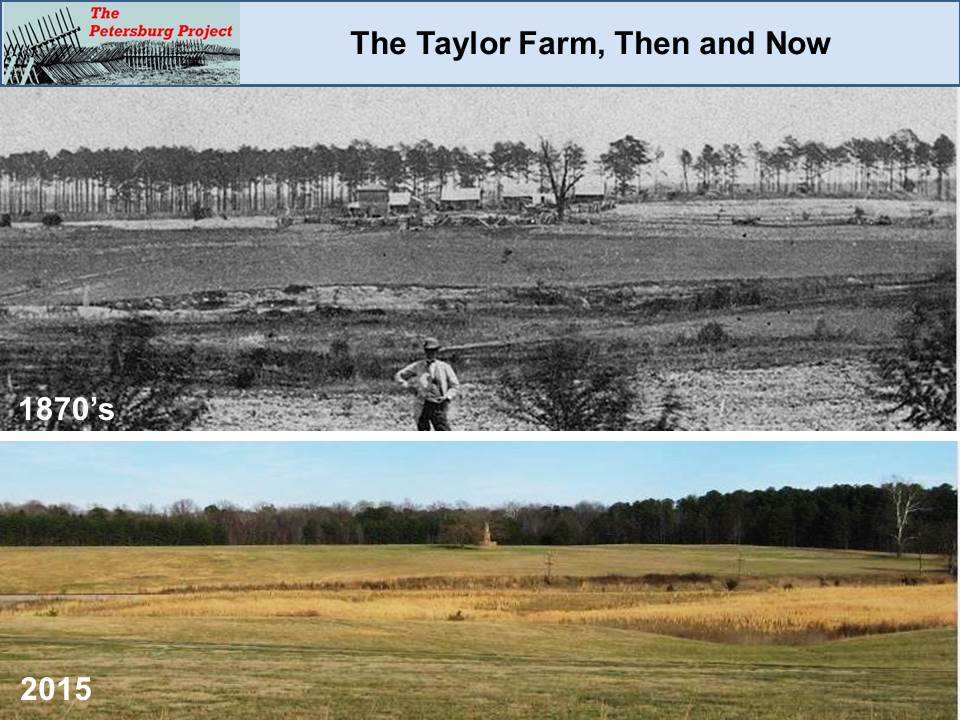

Unlike many landowners whose holdings had been devastated by the war, Taylor quickly rebuilt his farmstead. Even more remarkably, he managed to level most of the massive earthworks that covered his lands and put his fields back into agricultural production, although it took him years to do it.

The top photograph from the early 1870s (private collection) looks directly east from the site of the Crater, across the Norfolk & Petersburg railroad, to the new structures. The two story house now standing in the center was built on the foundation of the original kitchen/slave quarters building. The original eighteenth century house was to the left or north of the new structure.

The bottom photograph shows the same scene today, with the chimney of the immediate post war structure visible.

Once again, the Federal government was responsible for the destruction of the Taylor farm, only this time it was by the National Park Service, for the worthy purpose of restoring the 1865 landscape!

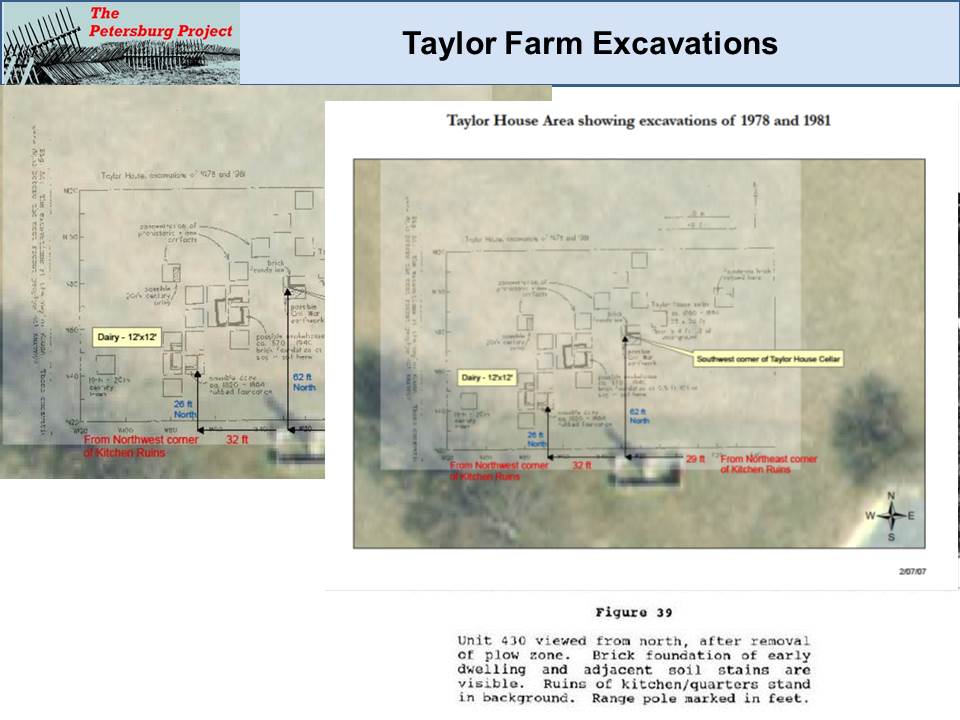

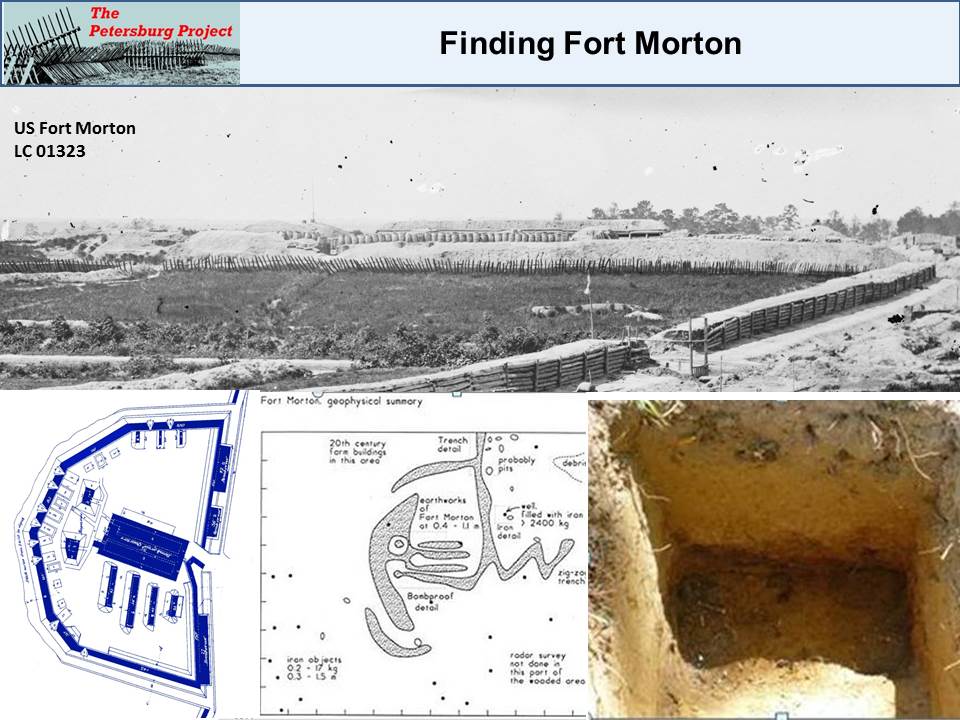

In 1978 and 1981 (Blades 1993) the National Park Service performed test excavations in the area, based on Bruce Bevan’s geophysical survey, which accurately pinpointed the location of the Taylor house cellar and relocated the corners of the Taylor house and several outbuildings. Bevan continued to explore the nearby Fort Morton location and found clear indications that the lower portions of the ditch in front of the fort and other subsurface features still existed below the modern fields.

In 1998 and 1999, the NPS Northeast Region archeology program ground-truthed the geophysical work as reported by Orr and Steele (2011). Bevan and Steele did additional geophysical work to verify the locations of Union Battery XIV (Bevan 2010) and a major Federal covered way that played a prominent role in the Battle of the Crater.

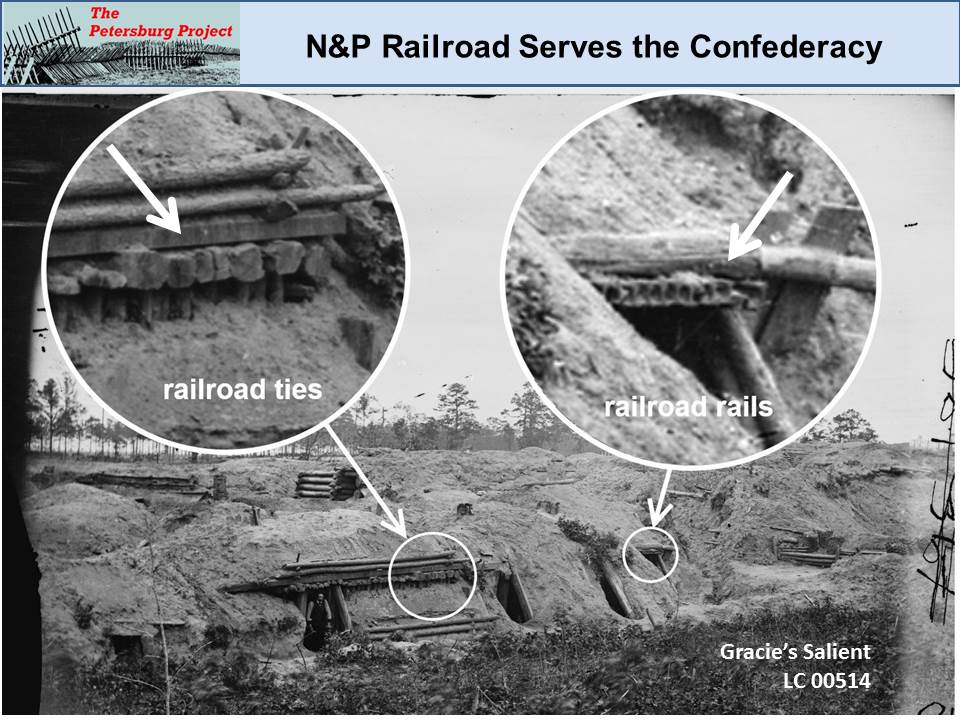

It wasn’t only buildings that offered themselves up for use by the contending armies. The iron rails and wooden ties of the various railroads were particularly useful for building bombproof shelters. These bombproofs are in Gracie’s Salient, where the Norfolk & Petersburg Railroad passed through the Confederate lines.

Once the Norfolk & Petersburg passed into the Union lines, the Federals stripped it for their own purposes. During the assault on June 18, Attacking Union troops piled up the ties to barricade the end of a deep railroad cut that was swept by enemy fire.

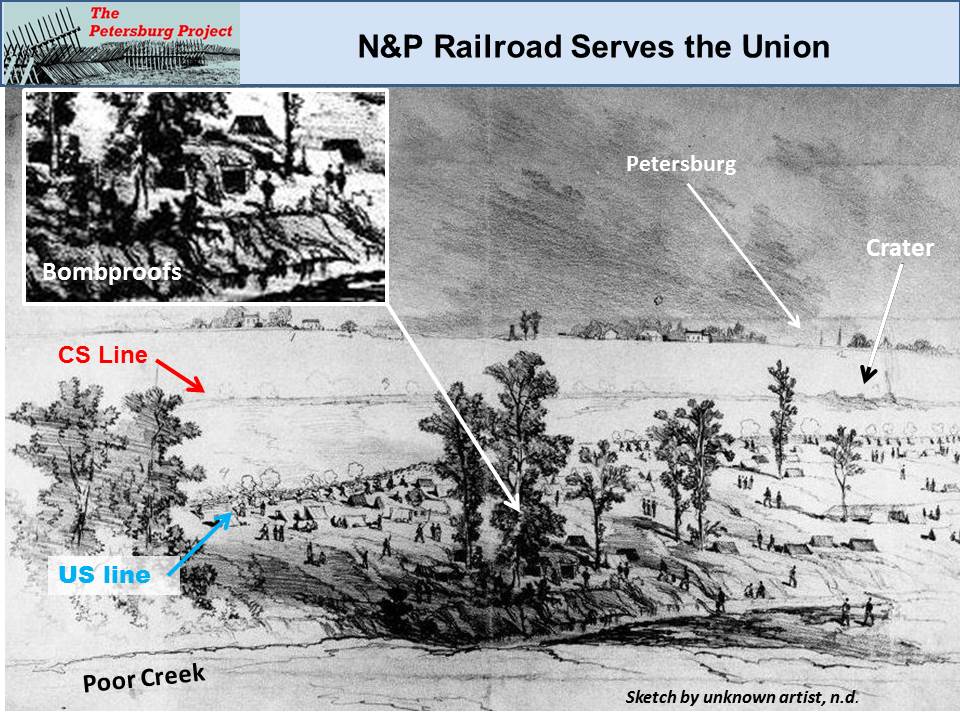

Colonel William J. Bolton of the 51st Pennsylvania participated in that charge and then held part of the advanced Union line west of the railroad in front of the Confederate fort blown up in the battle of the Crater. On July 1, 1864, he writes, “The 51st still holding the advance line. …I had a large hole dug in the bank at the foot of the hill in the rear of the regiment and built a bombprof [sic] of railroad sills and railroad iron, placing seven feet of earth on top. The Poo Creek was in front of it….” (Sauer 2000:221).

Bolton’s bombproof might have been one of those depicted in this drawing of the advanced Federal line.

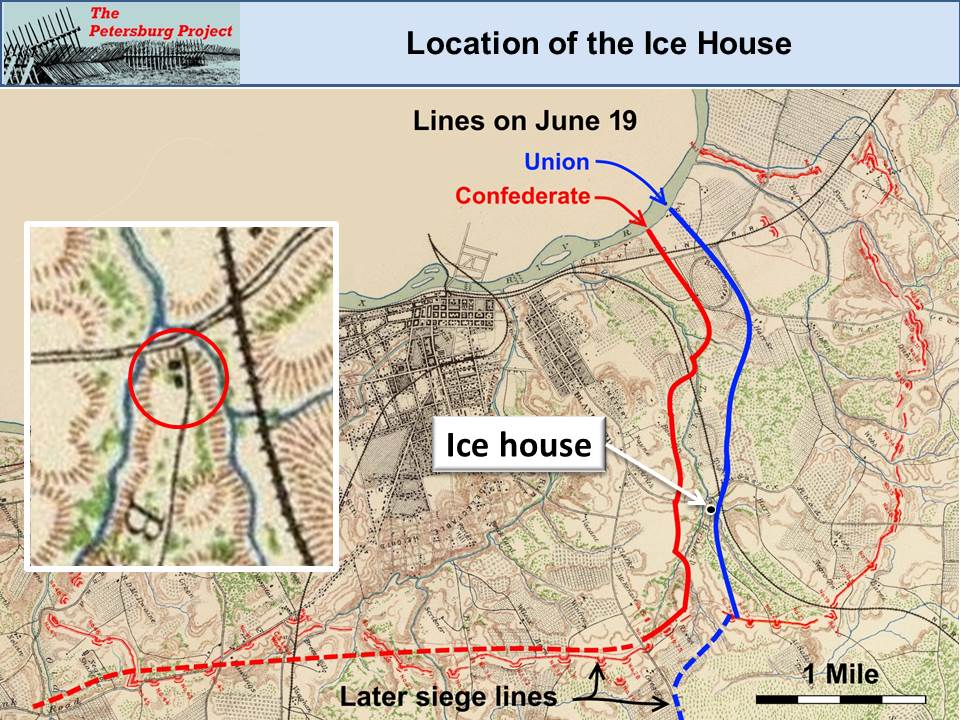

Another nearby feature was also a prominent battlefield landmark. Many early Federal accounts mention an icehouse near Baxter Road, west of the Taylor house. This structure was first mentioned in official reports of artillery actions on June 18th, when Mink’s battery, attached to the 5th Army Corps, was “firing up the track and driving the enemy from the clump of woods at the icehouse” (OR XL, Part I:482). The Ice House

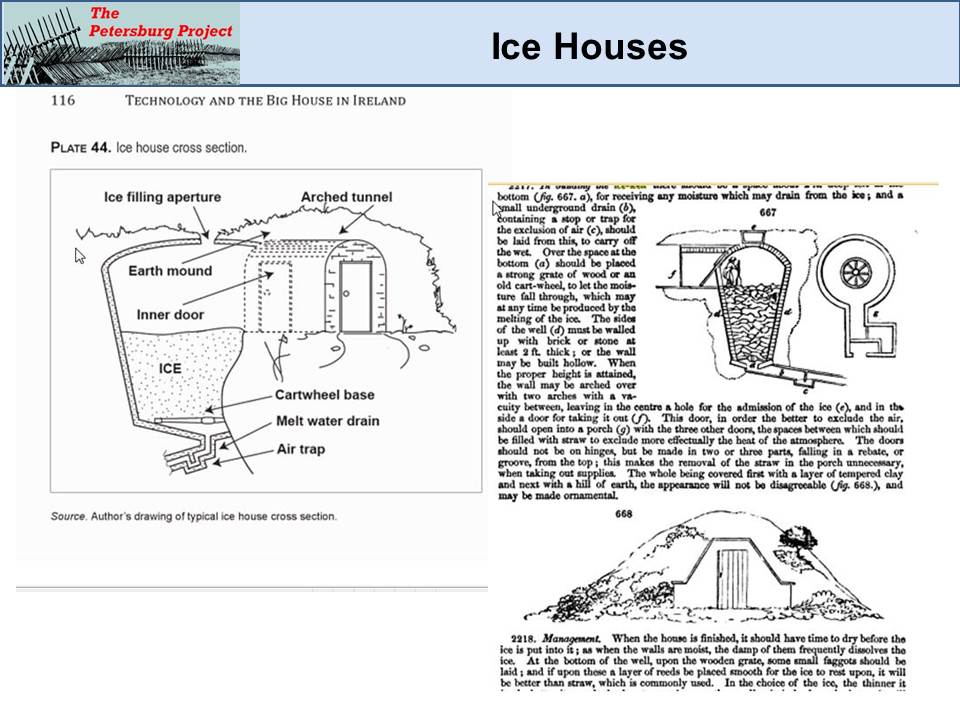

An icehouse, or ice well, consisted of an excavated hole, with additional features that contributed to its ability to insulate a supply of ice and snow harvested during the cold months, and to prevent the precious substance from melting away through the summer months when it could provide cooling drinks, desserts, and relief to the sick, as well as refrigerate perishable foodstuffs.

In a letter printed in the American Agriculturalist, written December 5, 1843, T. S. Pleasants of Petersburg wrote:

The best site for an ice-house is at the summit of a steep declivity, with a northern aspect. If trees about it, so much the better. When the pit is excavated it will not be a difficult matter to cut a drain on a level with the floor, either by ditch or tunnel (p. 370).

Within the underground structure, ice was further preserved by use of double walls, charcoal, sawdust or straw.

Ice houses on grand estates, such as Mount Vernon or Shirley plantation, tended to be large, brick structures, but they did not need to be particularly lavish. In the article mentioned above, T.S. Pleasants goes on to state:

The best ice-house I have ever seen is one made in as cheap and rude a manner as the plainest farmer could desire. On the side of a hill a pit was dug: a simple pen of logs supported the walls; it was covered with rived pine slabs; …. And withal, the pit is only 12 feet square, by 14 feet deep (p. 370).

By the mid-nineteenth century, ice was a widely traded commodity. The index of local newspapers available online at the Library of Virginia, shows that by the 1860s ice was arriving at the port of Petersburg from places such as Rockport, Massachusetts, and Kennebunkport, Maine.

In a letter printed in the American Agriculturalist, written December 5, 1843, T. S. Pleasants of Petersburg wrote:

The best site for an ice-house is at the summit of a steep declivity, with a northern aspect. If trees about it, so much the better. When the pit is excavated it will not be a difficult matter to cut a drain on a level with the floor, either by ditch or tunnel (p. 370).

Within the underground structure, ice was further preserved by use of double walls, charcoal, sawdust or straw.

Ice houses on grand estates, such as Mount Vernon or Shirley plantation, tended to be large, brick structures, but they did not need to be particularly lavish. In the article mentioned above, T.S. Pleasants goes on to state:

The best ice-house I have ever seen is one made in as cheap and rude a manner as the plainest farmer could desire. On the side of a hill a pit was dug: a simple pen of logs supported the walls; it was covered with rived pine slabs; …. And withal, the pit is only 12 feet square, by 14 feet deep (p. 370).

By the mid-nineteenth century, ice was a widely traded commodity. The index of local newspapers available online at the Library of Virginia, shows that by the 1860s ice was arriving at the port of Petersburg from places such as Rockport, Massachusetts, and Kennebunkport, Maine.

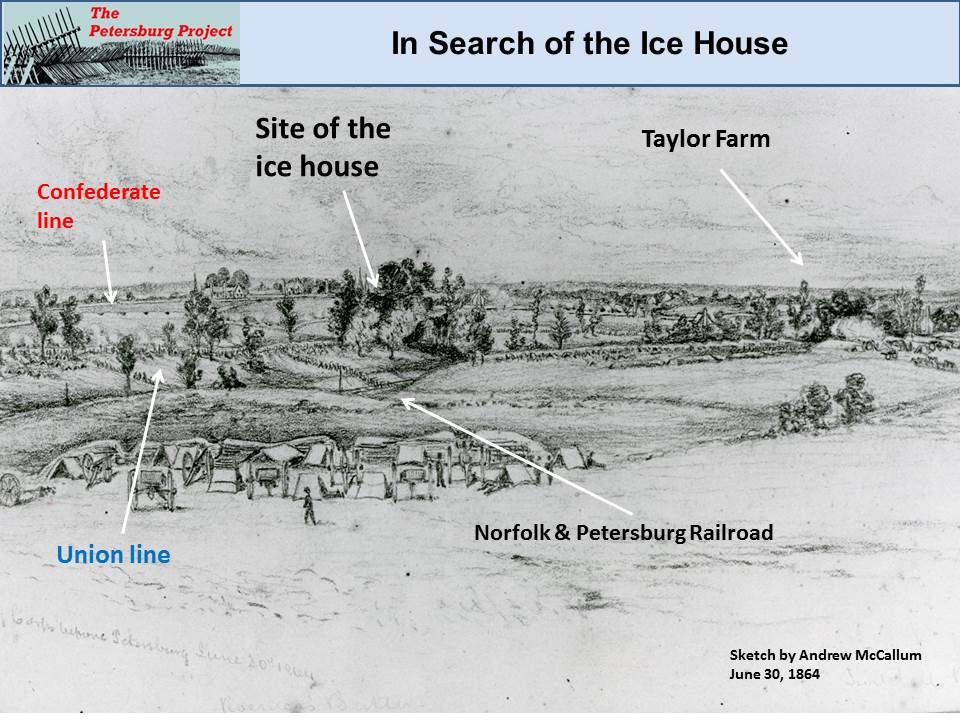

Soldiers attacking and defending Petersburg, Virginia, in mid-June 1864 had more to contend with than the enemy’s artillery and musketry: both sides had to operate in almost unbearable heat. Under these trying circumstances, it is not surprising that the combatants took note of a common structure unfamiliar to the modern world, but recognizable in the nineteenth century; an icehouse. William Hodgkins of the 36th Massachusetts Volunteers reported in a diary of the trenches (1884:228):

July 8th. ... Lately our men discovered an ice-house in front of our line…, and for a while it has been neutral ground for one or two men from the opposing lines to get ice, to the extent that if anyone has been seen near the ice-house they have not been fired upon. To-day, however, Corporal Lucius Lowell, of Company F, in endeavoring to get some ice, was fired upon, and received two bad wounds in the breast and wrist.

Does the icehouse still exist? From these accounts and others, we know it was near the Taylor house, near the Norfolk & Petersburg Railroad, near the Baxter Road, and near a clump of trees. It was originally in territory that men from both sides of the conflict could reach, if brave or foolish enough.

On July 22nd, Colonel William Humphrey, as General of the Trenches for the 9th Army Corps, reports that “four pieces of Captain Twitchell’s battery have been so placed as to sweep the ravine and cornfield in front ... Two of these pieces are to the right of the burnt house [Taylor house], and two in the front line near the ice-houses.” (OR XL, Part III: 396).

July 8th. ... Lately our men discovered an ice-house in front of our line…, and for a while it has been neutral ground for one or two men from the opposing lines to get ice, to the extent that if anyone has been seen near the ice-house they have not been fired upon. To-day, however, Corporal Lucius Lowell, of Company F, in endeavoring to get some ice, was fired upon, and received two bad wounds in the breast and wrist.

Does the icehouse still exist? From these accounts and others, we know it was near the Taylor house, near the Norfolk & Petersburg Railroad, near the Baxter Road, and near a clump of trees. It was originally in territory that men from both sides of the conflict could reach, if brave or foolish enough.

On July 22nd, Colonel William Humphrey, as General of the Trenches for the 9th Army Corps, reports that “four pieces of Captain Twitchell’s battery have been so placed as to sweep the ravine and cornfield in front ... Two of these pieces are to the right of the burnt house [Taylor house], and two in the front line near the ice-houses.” (OR XL, Part III: 396).

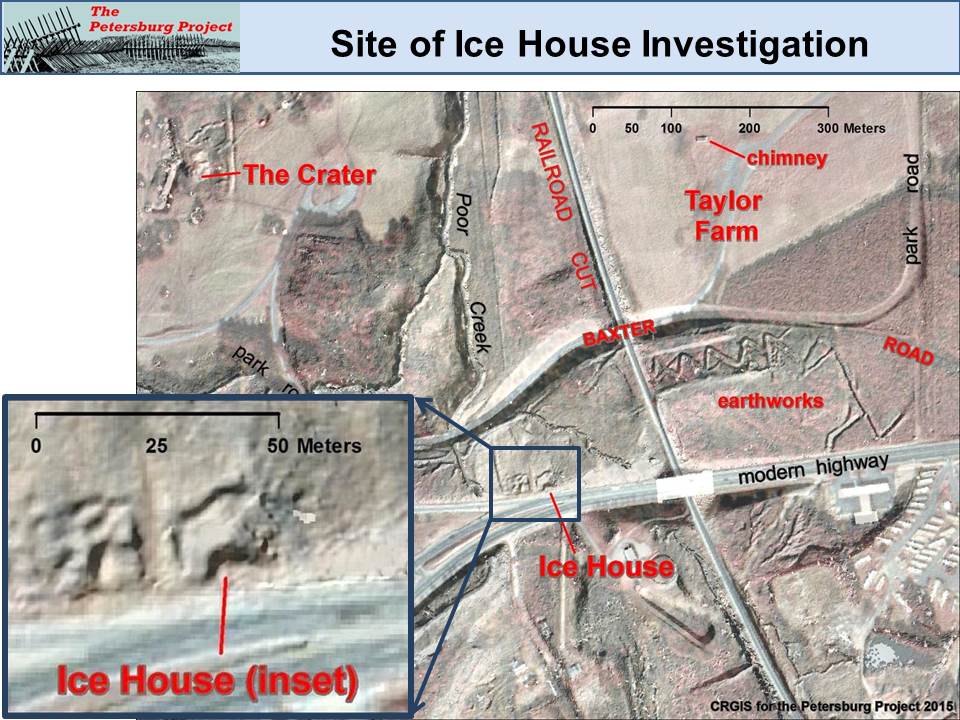

A LIDAR image of this sector of the park showed a set of unusual features, cut into by a modern state road, but obscured by heavy vegetation. Although these features were near a Federal rifle trench and an artillery position mapped on the end-of-the-war Michler map, these did not look like other military bombproof features in the park. They were in the location of two unnamed structures located on a farm lane on the 1863 Confederate Gilmer map. Could one or both of these be an ice-house?

A field visit was intriguing, especially since modern surface finds seemed to predict we were on the right track. These structures were on the northern side of the crest of a hillside, which fit the prescription for an ice-house, but was a poor position for a military feature because it could be hit by artillery fire from both sides of the conflict. The eastern feature had a particularly deep depression in its center where the roof of the structure had caved in, consistent with a deep subsurface cavity. The surface of the feature was earthen with no indication of masonry construction.

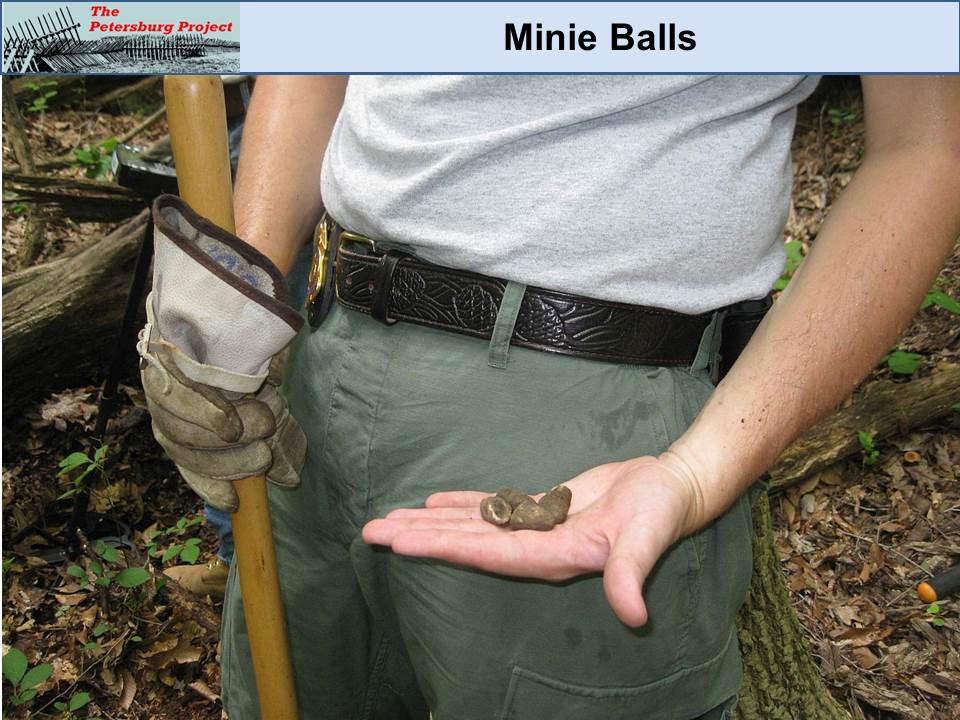

Colleagues suggested the features might be remnants of highway construction. This did not seem likely and a limited metal detector survey put this idea to rest. The survey recovered scores of impacted Civil War bullets, shrapnel, canister, and cut nails on the outer wall of the eastern feature in undisturbed context. We did not find tools that would be expected at an icehouse, such as saws, tongs, chisels or ice bars. That was, of course, wishful thinking.

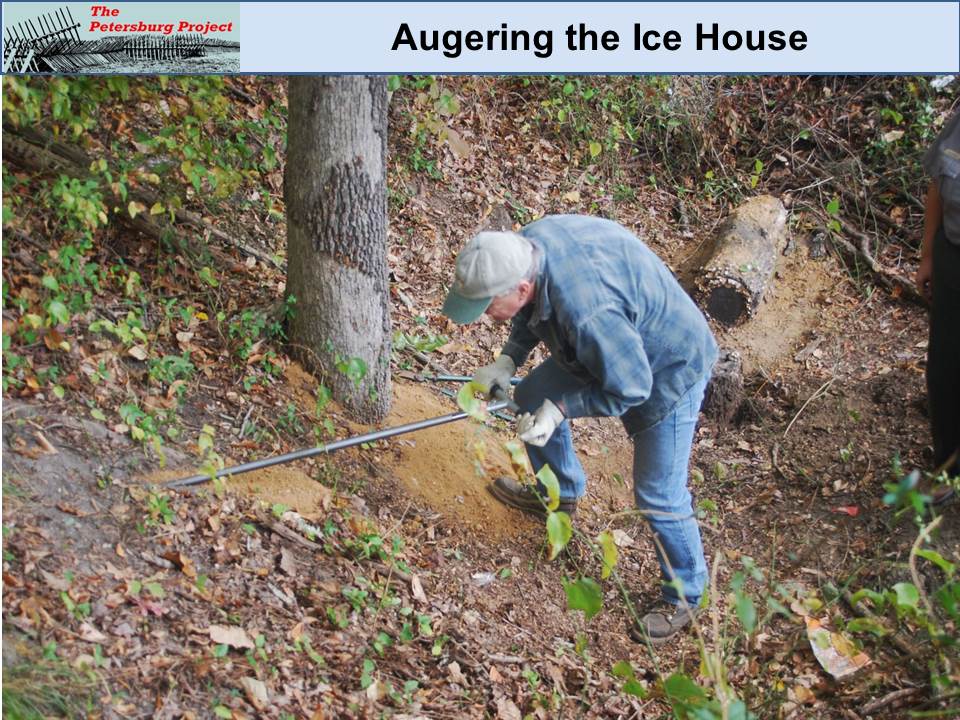

A limited testing program with a hand auger with a 3” bucket provided promising results. In the center depression, charcoal fragments were mixed throughout the clayey soil to a depth of 6.5 feet below the modern surface when sterile soil was encountered. This would imply the original depth of the feature was over 12’ deep, deeper than a bombproof would be.

Auguring into the west side of the structure in two locations, we found charcoal flecks throughout the soil, then a distinct charcoal layer, about an inch thick where a wall lining would likely have been.

It is likely that any surface or sub-surface structure associated with the icehouse, whether masonry or wood, was destroyed by Federal troops after the armies had consumed the precious ice, under fire in the hot southern sun. Bricks or timber, which were in short supply south of the Taylor Farm due to the lack of habitations, would have been used to provide shelter and warmth as the siege wound on into winter.

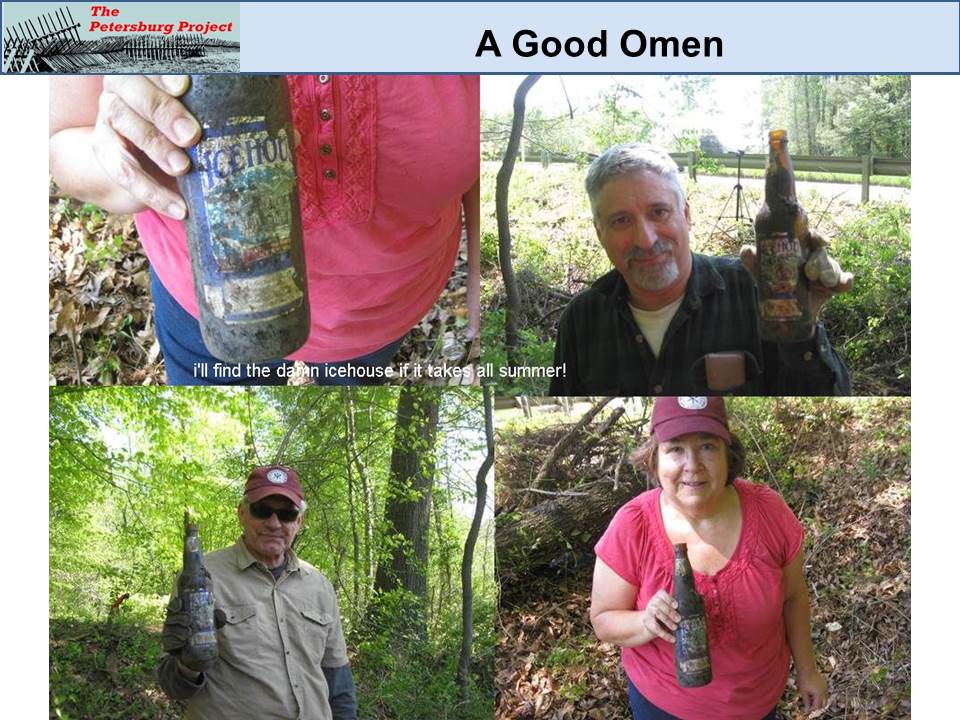

We did find an artifact in the feature that we consider a sign that we are definitely on the right track…

Conclusions

Identification of battlefield landmarks, or character defining features or contributing elements in historic preservation parlance, has long been considered a valid research interest for historians and archeologists. These features, whether they be natural or human made, can affect the course of battles as they provide cover, prove to be obstacles, or serve as observation points, command centers, or any of a number of other functions, not the least of which is providing a reference point for a specific sector of the battlefield.

The houses and ice-house are important reference points even though the structures themselves did not last long as conflict raged around Petersburg. They each remain on the scene, although it takes effort to find their footprint. The railroad remains an obvious landmark, as it is still in use on the same right of way. Its scavenged materials remain hidden as the underground warren of bombproof shelters settles into indeterminate, overgrown piles of earth with iron and timber skeletons. We hope we have illustrated some of their unusual site formation processes.

References

Bevan, Bruce

1996 Geophysical exploration for archaeology. Geosight Technical Report No. 4.

Bevan, Bruce

2010 Geophysical Exploration of Battery XIV. Ms., National Park Service.

Blades, Brooke

1993 Archeological Excavations at the Taylor House Site, Petersburg National Battlefield, Virginia. Ms., National Park Service.

Charles, Henry Fitzgerald

n.d. Memoirs. http://www.beyondthecrater.com/resources/lt/c-lt/charles-henry-f/henry-f-charles-memoirs-the-second-battle-of-petersburg-june-18-1864/

Hodgkins, William

1884 In History of the Thirty-Sixth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, Henry Sweetser Burrage, editor. Rockwell and Churchill, Boston.

O.R.

1881 The War of the Rebellion: A compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Government Printing Office, Washington.

O. R. Atlas

1863 Map of the approaches to Petersburg and their defenses, 1863, prepared by A. H. Campbell, CSA, 1863. O.R. Atlas Plate XL, No. 1

1895 Atlas to accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Government Printing Office, Washington.

Orr, David G. and Julia L. Steele

2011 Mapping Early Modern Warfare: The Role of Geophysical Survey and

Archaeology in Interpreting the Buried Fortifications at Petersburg, Virginia. In

Historical Archaeology of Military Sites: Method and Topic, Clarence R. Geier,

Lawrence E. Babits, Douglas D. Scott and David G. Orr, eds., Texas A & M

University Press, College Station.

Sauer, Richard

2000 The Civil War Journals of Colonel Bolton, 51st Pennsylvania. DaCapo Press, Boston.