The Rebel in the Road (and How He Got There)

By Philip Shiman and David Lowe (published on-line May 14, 2011)

On April 1, 1865, after more than nine wearying months of stalemate at Petersburg, a Union task force decisively defeated and scattered a Confederate detachment at Five Forks, exposing the flank of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s defense line covering Petersburg and Richmond. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant determined to hasten the end of the siege by ramming his soldiers through Lee’s overstretched Army of Northern Virginia. The next dawn, on April 2, the Army of the Potomac launched two all-out frontal assaults. The Ninth Corps, under Maj. Gen. John G. Parke, charged up the Jerusalem Plank Road southeast of Petersburg, while a few miles to the west Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright hurled his Sixth Corps against the line in front of the Boydton Plank Road. The Ninth Corps seized the first Confederate line but was halted by determined counterattacks and Confederate artillery on the second line. The Sixth Corps made a clean breakthrough, cutting off the right flank of Lee’s army and forcing him to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond that night. Six days later Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox Court House.

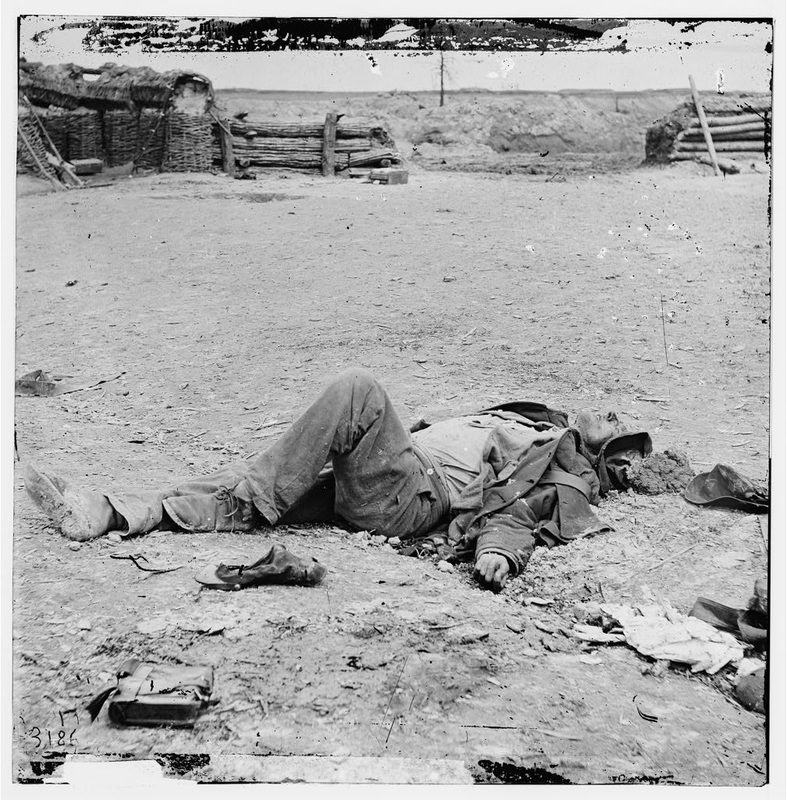

No photographers were present at the sites of Five Forks or the Sixth Corps breakthrough, but at least two were on hand at the Jerusalem Plank Road after the charge of the Ninth Corps -- Capt. Andrew J. Russell and Thomas C. Roche. On April, 3, the morning after the battle, as the armies marched westward, these photographers hurried forward to record the results of the fighting. By Russell's own account, Roche was first on the field. "I found Mr. Roche on the ramparts," wrote Russell, "with scores of negatives taken where the fight had been the thickest and where the harvest of death had indeed been gathered - pictures that will in truth teach coming generations that war is a terrible reality. A few minutes later I saw his van flying towards the war-stricken city ....." By the time Roche had maneuvered his wagon through the muddy, cut-up battlefield, it is likely that all of the Federal dead had been buried. A burial party (some of whom appear in his photos) had started to inter the Confederates, and Roche was but a few steps in front of their shovels. This dead Rebel's image was captured by Thomas Roche.

No photographers were present at the sites of Five Forks or the Sixth Corps breakthrough, but at least two were on hand at the Jerusalem Plank Road after the charge of the Ninth Corps -- Capt. Andrew J. Russell and Thomas C. Roche. On April, 3, the morning after the battle, as the armies marched westward, these photographers hurried forward to record the results of the fighting. By Russell's own account, Roche was first on the field. "I found Mr. Roche on the ramparts," wrote Russell, "with scores of negatives taken where the fight had been the thickest and where the harvest of death had indeed been gathered - pictures that will in truth teach coming generations that war is a terrible reality. A few minutes later I saw his van flying towards the war-stricken city ....." By the time Roche had maneuvered his wagon through the muddy, cut-up battlefield, it is likely that all of the Federal dead had been buried. A burial party (some of whom appear in his photos) had started to inter the Confederates, and Roche was but a few steps in front of their shovels. This dead Rebel's image was captured by Thomas Roche.

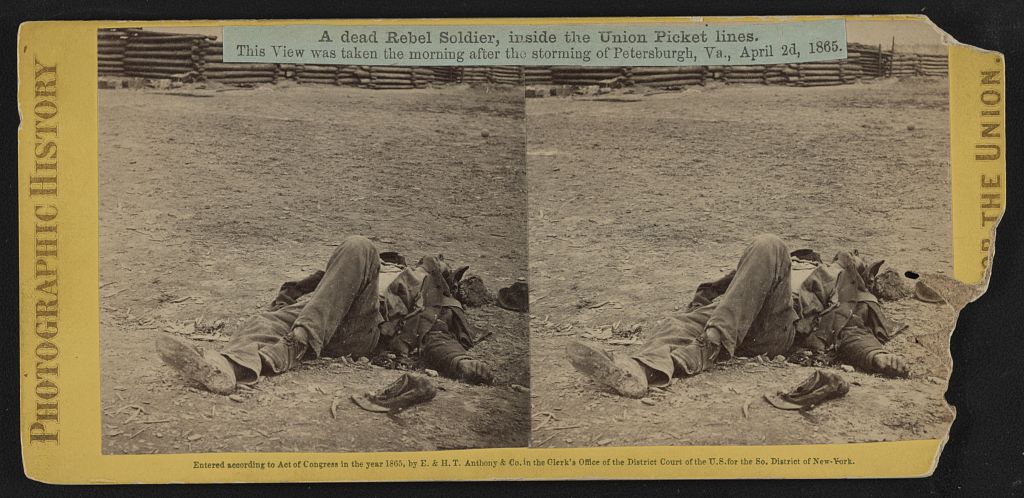

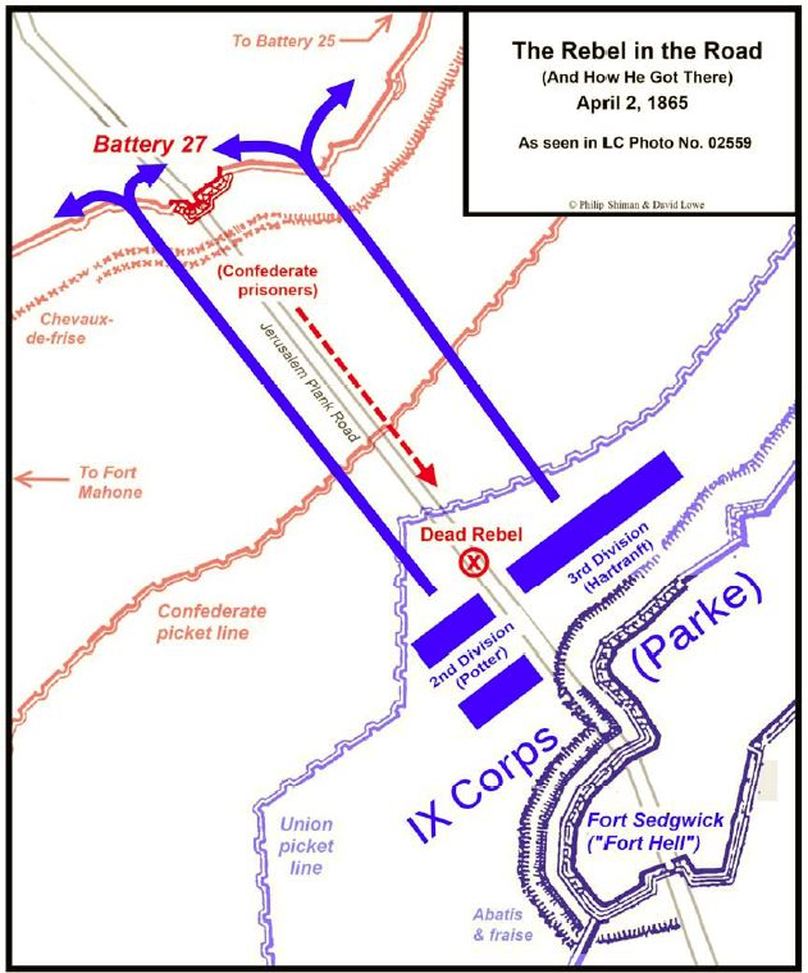

His wound is not obvious, but by the discoloration of the soil he appears to have been hit in the back of the head by a bullet or shell fragment. Like most of the dead Confederates photographed that day, he is well-dressed, with a uniform that looks almost new albeit muddy and disheveled by looters. There are weary and bored Yankee grave-diggers nearby, out of sight of the camera, waiting to lay him in his final resting place. We may never know his name, but by closely studying other photographs taken the same day—which thanks to modern technology can be easily enlarged and enhanced—we can determine where he was lying and the tragic circumstances of his death. The location of the body has been a matter of dispute. He is clearly within a picket line; the rear of a sharpshooter’s post is plainly visible in the background. But whose? The caption for this image says only that he is “a dead Confederate soldier.” However, a related view taken from a slightly different angle describes him as being “inside the Union Picket lines.”

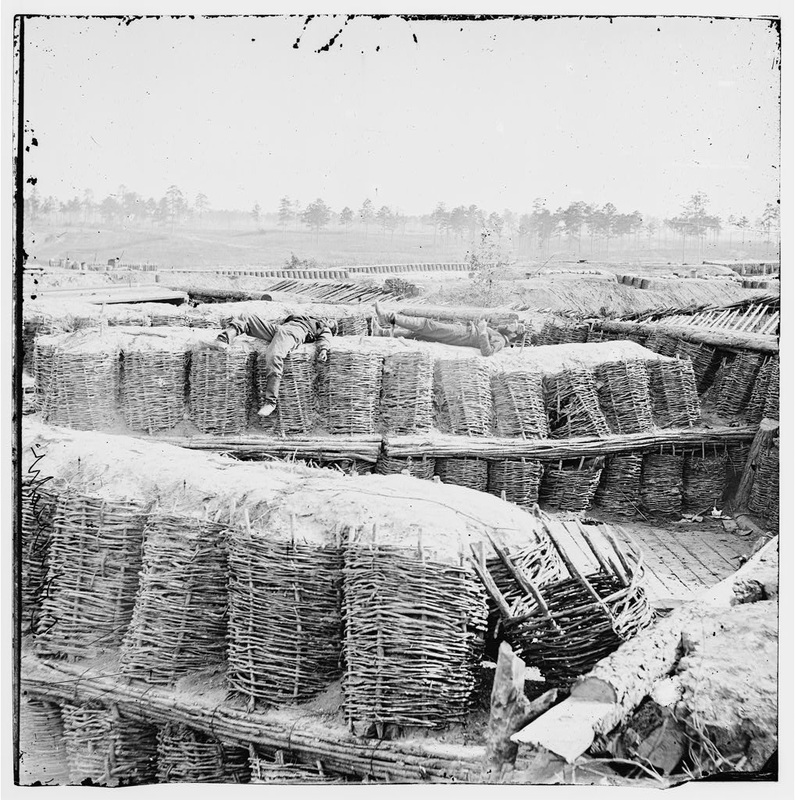

A dead rebel soldier, inside the Union Picket lines. Several other images taken from this location show Federal soldiers posed in these picket posts. The "manned" post below is the backdrop for the dead rebel in our initial photograph, as is revealed by many details of construction and the wear and tear on the dirt-filled wicker baskets that made up the position. The captions for this series (likely staged by photographer Andrew Russell) explicitly identify the location as the “Federal picket line in front of Fort Mahone.” Two soldiers posed in the foreground are aiming at others standing on an entrenched line the in the distance. This image was staged to show how close the combatants were to one another.

A second image in this series gives us a wider view of the picket posts, all similarly piled up from the same wicker baskets called "gabions." The picket post above is the one on the far right in the image below. The same soldier with the rubberized cover for his kepi is featured in the foreground of both images. This wider view below is very important for confirming the identity of this picket line.

All of these images have been discussed and speculated upon over the years. In his study of the photos from the Overland Campaign, Grant and Lee (1983), historic photographic expert William Frassanito rejected the notion that the dead rebel could be within the Union lines. "No Southern soldiers are known to have fallen beyond their own original positions during the fighting on April 2, 1865," he writes (364). He concludes that the works in the background of our initial photo "were almost definitely Confederate." Ergo, the rebel in question is lying within his own picket line.

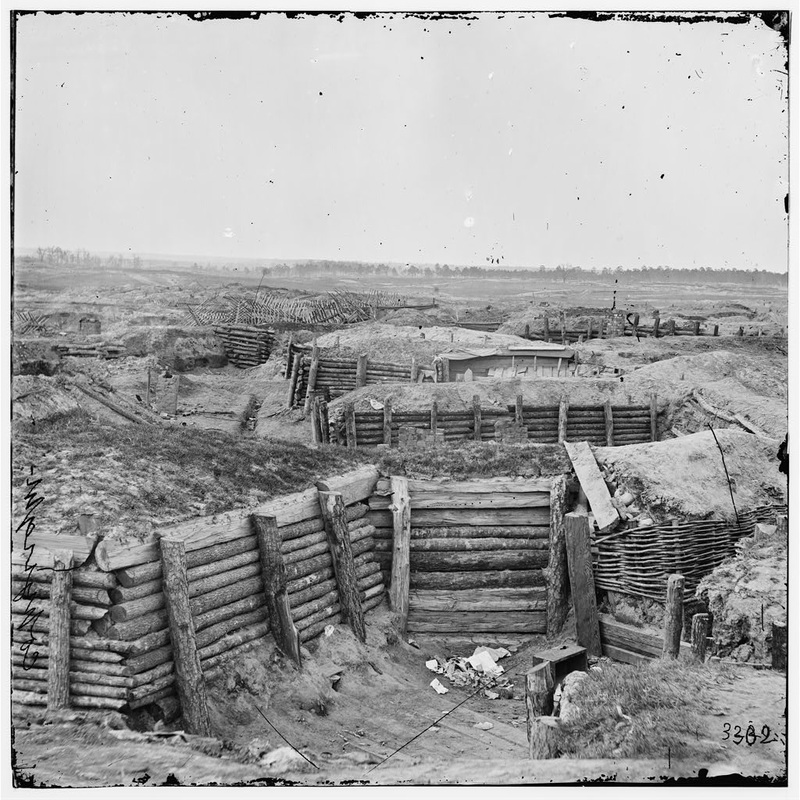

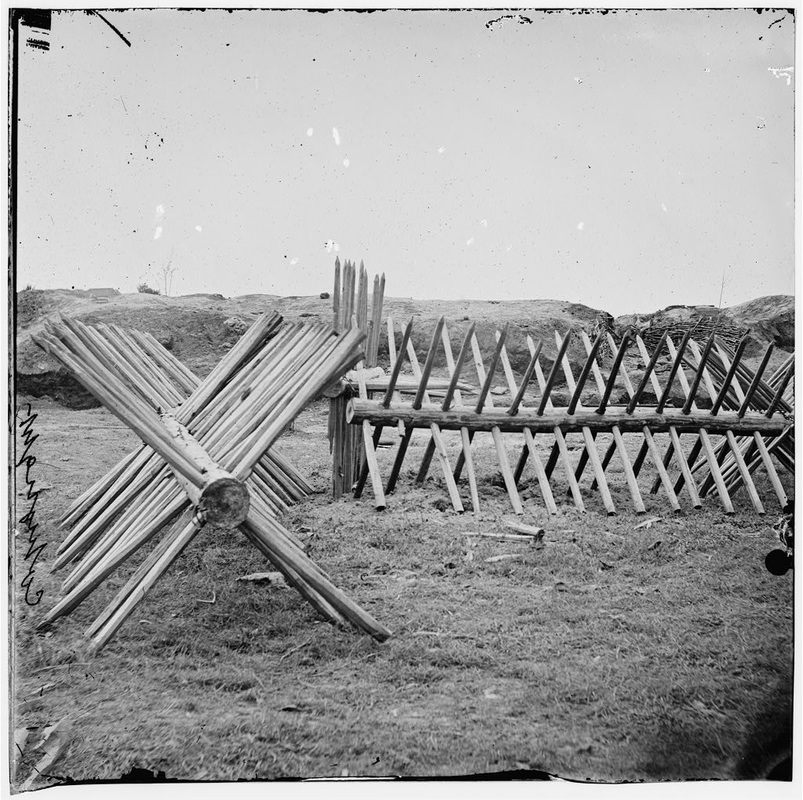

Yet the photographs themselves contain important clues as to the owner of this picket line. First is the fact, as pointed out, that the posts were built with gabions -- wickerwork cylinders that when filled with earth functioned as a sort of woven sandbag. Long bundles of saplings, called fascines, were also typically used in conjunction with gabions, and examples are seen above making up the retaining wall to the right and left of the picket post. These materials made an excellent support for earthen fortifications, and the Union engineers preferred gabions and fascines to logs, which had the nasty habit of splintering when struck by cannonballs and skewering defenders. The main limitation on their use was the supply of raw materials and manpower. On this part of the front, though, the Federal army had access to a rich supply of excellent raw materials, such as alder saplings, in the woods behind the lines and in the Blackwater Swamp a bit further to the rear. They also had many spare troops here early in the siege, and the troops of the Engineer Battalion taught them how to make gabions. They made thousands and used them almost exclusively to build the forts near where these photographs were taken. The photo below shows the predominance of gabion-fascine construction in Federal Fort Sedgwick (also known as "Fort Hell.")

Yet the photographs themselves contain important clues as to the owner of this picket line. First is the fact, as pointed out, that the posts were built with gabions -- wickerwork cylinders that when filled with earth functioned as a sort of woven sandbag. Long bundles of saplings, called fascines, were also typically used in conjunction with gabions, and examples are seen above making up the retaining wall to the right and left of the picket post. These materials made an excellent support for earthen fortifications, and the Union engineers preferred gabions and fascines to logs, which had the nasty habit of splintering when struck by cannonballs and skewering defenders. The main limitation on their use was the supply of raw materials and manpower. On this part of the front, though, the Federal army had access to a rich supply of excellent raw materials, such as alder saplings, in the woods behind the lines and in the Blackwater Swamp a bit further to the rear. They also had many spare troops here early in the siege, and the troops of the Engineer Battalion taught them how to make gabions. They made thousands and used them almost exclusively to build the forts near where these photographs were taken. The photo below shows the predominance of gabion-fascine construction in Federal Fort Sedgwick (also known as "Fort Hell.")

On the other hand, the Confederates directly in front of Petersburg had less "weavable" vegetation to work with, and much of that consisted of hardwood trees that were ill-suited to gabion construction. Furthermore, the Army of Northern Virginia lacked the spare manpower and wagons to find, gather, and haul the materials that were available, and the Southern engineers were kept busy digging countermines. Therefore, the Southerners were more stingy in their use of gabions and used very few, relying instead on logs, which were plentiful as witnessed below in this view of Battery 25.

The gabion and fascine construction of the picket posts in our photographs ensures they are Federal. But other decisive clues can be found by enhancing and enlarging these two picket-line photos with posed soldiers and looking closely at their backgrounds. Plainly visible on the horizon are the trenches and batteries of the enemy’s main line, protected by fearsome-looking wooden obstacles, called chevaux-de-frise. It is clear that soldiers firing from these positions would be shooting at the Rebels.

The obstacles known as chevaux-de-frise consisted of logs bored through in such a way as to permit two rows of sharpened stake to project at right angles. The logs were then chained together to form a long, unbroken fence that, like the barbed wire of later wars, was intended to slow an enemy attack under close range of the defenders’ guns. The Confederate army relied heavily on chevaux-de-frise at Petersburg and covered nearly their entire front with them for various reasons -- raw materials were abundant, the obstacles could be prepared in rear of the lines by work gangs, and then carried to the front, and installed in relative safety after dark.

Federal engineers had little confidence in chevaux-de-frise and rarely used them as primary obstacles. basically for reasons demonstrated in the above image. The chains linking the sections could be cut through with an ax and then the sections manhandled out of the way. Federal engineers preferred a fraise, a long row of closely set, sharpened logs planted in the ground, nailed and wired together. Such a barricade was extremely difficult to dismantle under fire. Engineers of both sides also relied on abatis or abattis, consisting of a hedge of felled trees with the branches sharpened and interlaced. Federals, in particular, laid multiple rows of both abatis and fraise to delay any assaulting force. As shown below in this image of Fort Sedgwick, a fraise made a formidable obstacle.

The presence of an extensive chevaux-de-frise virtually guarantees that the forts in the background are Confederate and that the picket posts facing them are built up of Federal gabions. With little doubt, the dead Confederate is within the Union picket line. We can be more specific and suggest that he is laying on or very near the Jerusalem Plank Road. The smooth, packed surface shown in this and the other picket post photos is consistent with a road. The photographers stayed close to the roads that day because their wagons could not negotiate the trenches or the soggy ground left over from a rainstorm immediately preceding the battle of April 2nd. The opposing picket lines were closer here than anywhere else—only about 60 yards apart—so this was an interesting place to photograph.

Frassanito was correct in the sense that no Confederate unit willingly advanced beyond its own picket line during the battle. Surely, the Federals didn’t move the body after the battle—they buried the Confederates where they fell. So how did this man get inside the Union lines?

The answer is surprisingly simple: He was not there voluntarily.

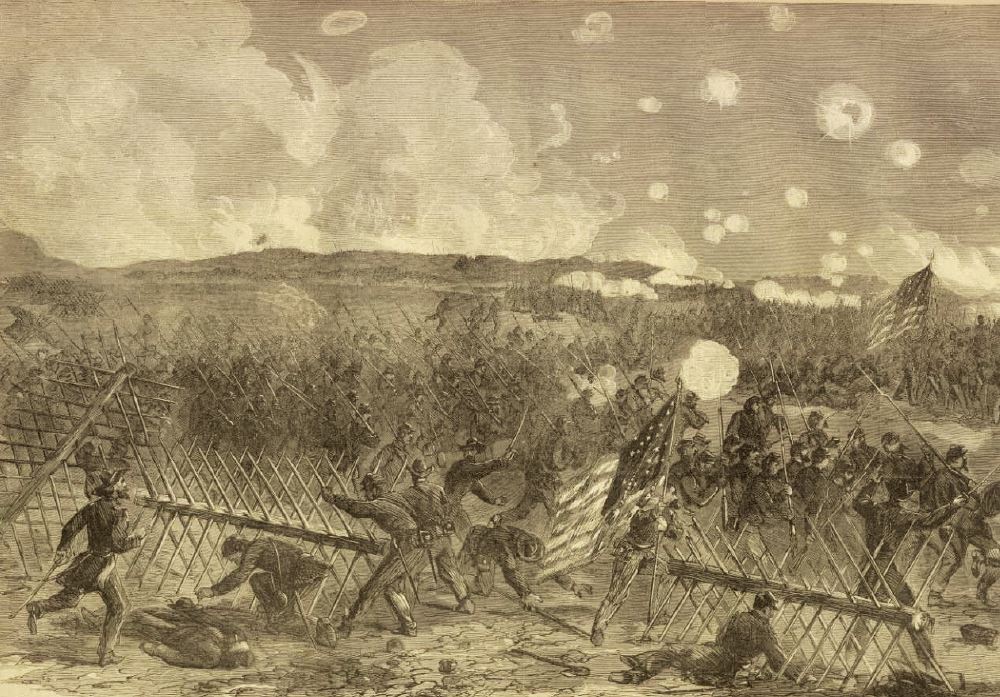

Just at daylight on April 2, two divisions of Maj. Gen. Parke’s Ninth Corps rose up from their positions behind the Union picket line and charged forward, overrunning the opposing pickets. The assault was directed straight up Jerusalem Plank Road. The attack was well-planned. Axe-men cut the chains linking the chevaux-de-frise together, and soldiers manhandled obstacles out of the way to surge forward against the main Confederate line at Battery 27. They carried picks, shovels, and gabions with them to build rapid defenses to defend their gains. Artillery crews crossed over to man the captured guns. Parke's four brigades, straddling the road, made a breach in the Confederate line that soon grew to over a half mile.

Frassanito was correct in the sense that no Confederate unit willingly advanced beyond its own picket line during the battle. Surely, the Federals didn’t move the body after the battle—they buried the Confederates where they fell. So how did this man get inside the Union lines?

The answer is surprisingly simple: He was not there voluntarily.

Just at daylight on April 2, two divisions of Maj. Gen. Parke’s Ninth Corps rose up from their positions behind the Union picket line and charged forward, overrunning the opposing pickets. The assault was directed straight up Jerusalem Plank Road. The attack was well-planned. Axe-men cut the chains linking the chevaux-de-frise together, and soldiers manhandled obstacles out of the way to surge forward against the main Confederate line at Battery 27. They carried picks, shovels, and gabions with them to build rapid defenses to defend their gains. Artillery crews crossed over to man the captured guns. Parke's four brigades, straddling the road, made a breach in the Confederate line that soon grew to over a half mile.

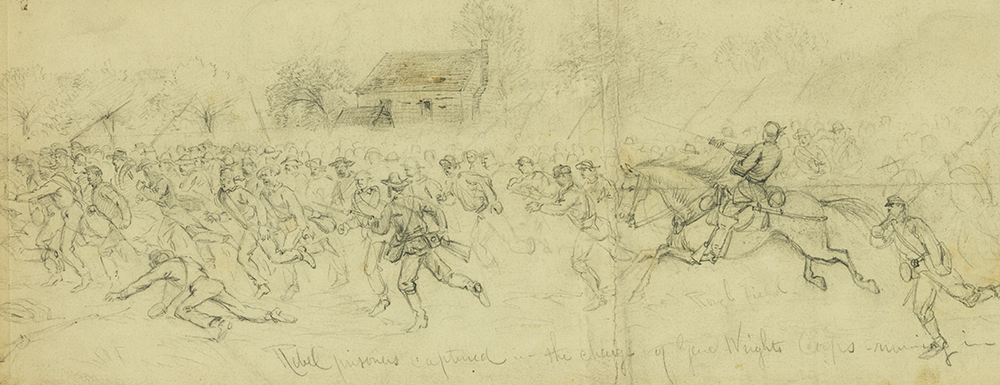

The storming of Battery 27 yielded a rich haul that according to Parke included 12 guns and 800 prisoners. During the attack, sections of chevaux-de-frise were carried to the rear of the battery (north of the line of assault) and piled up as a defense. The captured guns were turned and used to help fight off the fierce Southern counterattacks that followed. Unfortunate Confederate prisoners were disarmed and sent "running in" to the rear. We may assume they took the most direct route back to the Union lines, straight down the Jerusalem Plank Road. But Confederate batteries continued to blast away from their second line, turning what had been no man’s land into a gauntlet of death that did not discriminate among the uniforms of those crossing it: Federal reinforcements, fatigue parties bringing up ammunition and entrenching tools, couriers, the wounded—and prisoners. We should not be surprised that some of those 800 prisoners never completed their journey, including our unknown rebel, struck down within sight of the safety of Fort Sedgwick.

The Waud sketch above depicts the "running in" of prisoners captured by the Sixth Corps a few miles to the west of the Ninth Corps’ assault. The running in of prisoners along Jerusalem Plank Road was similarly chaotic. And the results for some, including our Rebel in the road -- were fatal.

The sequence of images suggests that Roche was held up at Fort Sedgwick by Federal pickets until late morning before he was allowed to proceed north on the Jerusalem Plank Road toward Confederate lines. He was then kept waiting at the Confederate picket line before being allowed to proceed. By the time he reached Battery 27 on the main line, corpses were rapidly disappearing underground. In the opinion of the Petersburg Project, this dead rebel in the road would have been the first body Roche encountered that day.