THE PETERSBURG PHOTOGRAPHS

Working with the Photographs

The value of the Petersburg PHOTOGRAPHS

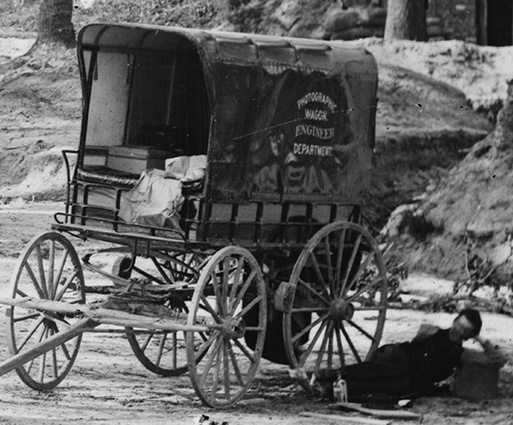

"Photographic Wagon Engineer Department," detail from image LC-DIG-cwpb-00531 taken at Fort Stedman, April 1865, by Timothy O'Sullivan.

"Photographic Wagon Engineer Department," detail from image LC-DIG-cwpb-00531 taken at Fort Stedman, April 1865, by Timothy O'Sullivan.

Photography in its various forms came into widespread use during the 1850s but came into its own during the Civil War. The American public had an appetite for photographs of the war but especially of the battlefields, with or without dead bodies. Photography also provided an important addition to the historical record. Indeed, many of the best known photographers, such as George Barnard, Andrew Russell, Thomas Roche, and Timothy O'Sullivan were actually employed by the Army Engineer Department to make images of fortifications, bridges, railroads, and quartermaster facilities. They "moonlighted" on the side with portraits and art. These photographers' work provides an unparalleled source of "real time" information about the soldiers, their war, and the terrain over which they fought.

Until recently, the thousands of surviving wartime images sheltered in various collections have been of limited value to historical research because of inaccessibility and low resolution reproduction.

Images in every collection have been misidentified and, sometimes intentionally, mislabeled to illustrate a narrative. Francis Trevylian Miller's ten-volume Photographic History of the Civil War (1911) was ground-breaking for its time, but Miller was intent on telling an epic story and did not shy from fitting misidentified images into his story. Despite recent scholarship, many of Miller's misidentifications continue to be perpetuated. Civil War scholars owe a special debt to William A. Frassanito and his three volumes of photographic interpretation and analysis: Gettysburg: A Journey in Time (1975); Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America's Bloodiest Day (1978); and Grant and Lee: The Virginia Campaigns 1864-1865 (1983). Frassanito demonstrated that these images were not abstractions but could and should be tied to reality. Since his publications, researchers refer to the act of finding a historic photo's location and viewing its modern equivalent, as "pulling a Frassanito." It is an informal way to acknowledge the contribution of the man and his vision.

Yet there is a limit to what even Frassinito could do with the photographs. The printed versions were too small and their resolution too low to do more than make a basic identification and view the major features. The original glass-plate negatives could be enlarged significantly with no loss of resolution, but the extent of the enlargement was limited by the capabilities of the equipment and the size of the photo paper, and in any event that process was too expensive to apply to the thousands of extant images. When it came time to publish them, applying the necessary half-tones cut down their resolution again, again limiting what the reader could see in them.

Starting in the 1990s, several interrelated technical developments helped eliminate these limitations on the use of contemporary photographs. The more powerful personal computer allowed images to be digitally processed, enhanced, and enlarged. Photo viewing and editing software provided the tools to do this, high-definition monitors allowed the results to be displayed accurately, and high resolution printers could print the images with greater detail. Also the cost of photographic enlargement began to drop dramatically. No less important was the arrival of high-resolution scanners and broad-band Internet connections, to allow the transmission of the high-resolution images then becoming available.

In a critical step forward, during the 2000s the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress began to scan its enormous collection of images, starting with its glass-plate negatives, followed by its paper prints and artists' sketches, and posting them on its searchable websites. Other institutions had begun to do the same, but their collections were usually made available for download in compressed (.jpeg) format. The Library of Congress posted not just .jpegs but also uncompressed (.tif) files that lost little detail when enlarged. The LOC first posted large (approximately 5000 x 5000 pixels for half of a stereographic image), high-resolution (1400 dpi or more) images. Soon after, it began posting extremely large (7500 x 7500 pixels), super-high resolution (2100 x 2100 dpi) versions. The Library made these available for anyone to download at no cost. A revolution was born.

It was now possible to download images on almost any subject, enlarge and enhance them, and pick them apart for details never before seen and that in fact are invisible to the naked eye on a standard print. The resolution of the glass-plate scans are particularly remarkable. We have been able to enlarge some of the the best-focused images with enough clarity to pick out certain details more or less reliably. We have managed to identify rifle loopholes perhaps inches across hundreds of yards from the camera. Yes, some of the images are that good--buttons, belt buckles, stencils on ammo boxes.

Civil War-era images are no longer merely decoration for narrative history, but now a valuable source of information in their own right. This is certainly the case in our studies with the Petersburg Project. The Library of Congress images not only make the siege come alive but these have quickly become an indispensable resource. After identifying the location of the camera and the subject of the view of each image involving the siegeworks and trench battles--a task in which we have had about a 90% success rate--we began picking apart each one for whatever secrets they yield. This is difficult task--as with ancient runes, one must learn to "read" an image and "translate" it into useful information, and to identify features the appearance of which is completely unknown to us.

Our analyses of the images, in conjunction with our site visits, have completely altered our understanding of the entrenched battlefield. There are a vast number of elements and features that were never recorded on any map and for which we have yet to find any documentation at any time, although we are still looking. Sometimes the images provide ideas about what to look for on the ground (and vice versa). Indeed, the Petersburg images have become a centerpiece of our work, hence the pride of place we accord them on this site. We do periodically venture out into other fields--the Library of Congress has posted excellent images of earthworks at Atlanta, Nashville, and many other places, all rich with details--but Petersburg is our home.

Until recently, the thousands of surviving wartime images sheltered in various collections have been of limited value to historical research because of inaccessibility and low resolution reproduction.

Images in every collection have been misidentified and, sometimes intentionally, mislabeled to illustrate a narrative. Francis Trevylian Miller's ten-volume Photographic History of the Civil War (1911) was ground-breaking for its time, but Miller was intent on telling an epic story and did not shy from fitting misidentified images into his story. Despite recent scholarship, many of Miller's misidentifications continue to be perpetuated. Civil War scholars owe a special debt to William A. Frassanito and his three volumes of photographic interpretation and analysis: Gettysburg: A Journey in Time (1975); Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America's Bloodiest Day (1978); and Grant and Lee: The Virginia Campaigns 1864-1865 (1983). Frassanito demonstrated that these images were not abstractions but could and should be tied to reality. Since his publications, researchers refer to the act of finding a historic photo's location and viewing its modern equivalent, as "pulling a Frassanito." It is an informal way to acknowledge the contribution of the man and his vision.

Yet there is a limit to what even Frassinito could do with the photographs. The printed versions were too small and their resolution too low to do more than make a basic identification and view the major features. The original glass-plate negatives could be enlarged significantly with no loss of resolution, but the extent of the enlargement was limited by the capabilities of the equipment and the size of the photo paper, and in any event that process was too expensive to apply to the thousands of extant images. When it came time to publish them, applying the necessary half-tones cut down their resolution again, again limiting what the reader could see in them.

Starting in the 1990s, several interrelated technical developments helped eliminate these limitations on the use of contemporary photographs. The more powerful personal computer allowed images to be digitally processed, enhanced, and enlarged. Photo viewing and editing software provided the tools to do this, high-definition monitors allowed the results to be displayed accurately, and high resolution printers could print the images with greater detail. Also the cost of photographic enlargement began to drop dramatically. No less important was the arrival of high-resolution scanners and broad-band Internet connections, to allow the transmission of the high-resolution images then becoming available.

In a critical step forward, during the 2000s the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress began to scan its enormous collection of images, starting with its glass-plate negatives, followed by its paper prints and artists' sketches, and posting them on its searchable websites. Other institutions had begun to do the same, but their collections were usually made available for download in compressed (.jpeg) format. The Library of Congress posted not just .jpegs but also uncompressed (.tif) files that lost little detail when enlarged. The LOC first posted large (approximately 5000 x 5000 pixels for half of a stereographic image), high-resolution (1400 dpi or more) images. Soon after, it began posting extremely large (7500 x 7500 pixels), super-high resolution (2100 x 2100 dpi) versions. The Library made these available for anyone to download at no cost. A revolution was born.

It was now possible to download images on almost any subject, enlarge and enhance them, and pick them apart for details never before seen and that in fact are invisible to the naked eye on a standard print. The resolution of the glass-plate scans are particularly remarkable. We have been able to enlarge some of the the best-focused images with enough clarity to pick out certain details more or less reliably. We have managed to identify rifle loopholes perhaps inches across hundreds of yards from the camera. Yes, some of the images are that good--buttons, belt buckles, stencils on ammo boxes.

Civil War-era images are no longer merely decoration for narrative history, but now a valuable source of information in their own right. This is certainly the case in our studies with the Petersburg Project. The Library of Congress images not only make the siege come alive but these have quickly become an indispensable resource. After identifying the location of the camera and the subject of the view of each image involving the siegeworks and trench battles--a task in which we have had about a 90% success rate--we began picking apart each one for whatever secrets they yield. This is difficult task--as with ancient runes, one must learn to "read" an image and "translate" it into useful information, and to identify features the appearance of which is completely unknown to us.

Our analyses of the images, in conjunction with our site visits, have completely altered our understanding of the entrenched battlefield. There are a vast number of elements and features that were never recorded on any map and for which we have yet to find any documentation at any time, although we are still looking. Sometimes the images provide ideas about what to look for on the ground (and vice versa). Indeed, the Petersburg images have become a centerpiece of our work, hence the pride of place we accord them on this site. We do periodically venture out into other fields--the Library of Congress has posted excellent images of earthworks at Atlanta, Nashville, and many other places, all rich with details--but Petersburg is our home.

what we do and how we do it

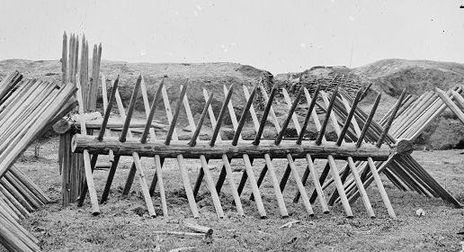

Typically, upon locating a new image, we examine it as a whole. Often, we could identify our later acquisitions at a glance, either because the image is a variant of one we or someone else had already identified. If a quick glance proved insufficient we would narrow down the possible location by assessing certain elements of the scene: the construction style or materials, the nature of the terrain, the photographer (who might have focused his work on a specific part of the battlefield), or even be the general appearance of the photo. Distinguishing Union from Confederate scenes was surprisingly easy. The defenses and living arrangements of the two sides displayed different styles, materials, and technologies. For example, the Federals employed sandbags and gabions extensively in building their works; the Confederates used few sandbags and fewer gabions. The presence of chevaux-de-frise--an infantry obstacle consisting of horizontal logs with four projecting rows of sharpened logs--in front of a fortification is a dead giveaway that it is Confederate. The Federals almost never used chevaux-de-frise, preferring fraise (rows of close-set sharpened stakes angling up from the ground) supplemented at times with abatis (hedges of tree-tops with sharpened branches).

Identifying an unknown image then involved examining increasingly smaller details in both the foreground and background for essential clues. Especially when looking at the background, it is often necessary to edit the image, altering it to bring out key details. (Purists and students of photography may object to this approach, but we are trying to extract and display information from these images, not admire their artistic beauty.) this can involve adjusting the contrast, midtones, sharpness, etc. We have found that different combinations of contrast and midtones adjustments work best.

Just a few moments' work with contrast and gamma adjustment brings out details from US Fort Morton (in front of the trees) and US Battery XV (just in front of Morton on the left). Detail from LC-DIG-cwpb-02610; the view is from CS Battery 25.

Working to bring the Images alive "pulling a frassanito"

View from inside Fort Haskell looking toward Fort Stedman. This Timothy O'Sullivan photograph (LC-DIG-cwpb-00532)

has been long mislabeled "Petersburg, Virginia. Fort Meikle ...." The top panel is the original image with Fort Stedman in the distance amid the clump of hardwoods. In the bottom panel, the background (beyond the parapet) from the original photo has been replaced with the background as seen from Fort Haskell today. The distant fort and batteries, the ravine, and slopes match perfectly. (See below.)

has been long mislabeled "Petersburg, Virginia. Fort Meikle ...." The top panel is the original image with Fort Stedman in the distance amid the clump of hardwoods. In the bottom panel, the background (beyond the parapet) from the original photo has been replaced with the background as seen from Fort Haskell today. The distant fort and batteries, the ravine, and slopes match perfectly. (See below.)

For additional information on how we identified Fort Haskell click here.

To go to images:

- the Siege of Petersburg

- The Siege of Atlanta (coming soon!

- the Siege of Nashville (coming soon!)

- the Siege of Vicksburg (coming soon!)