French Rifle Pits

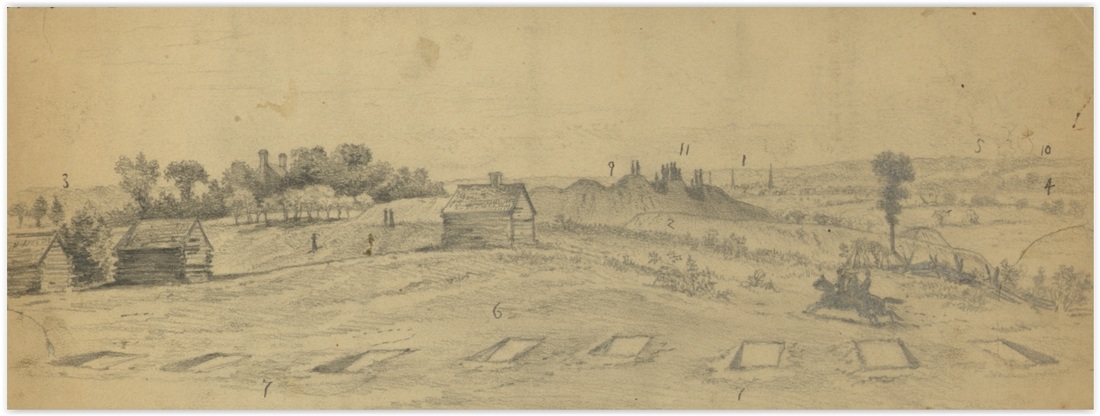

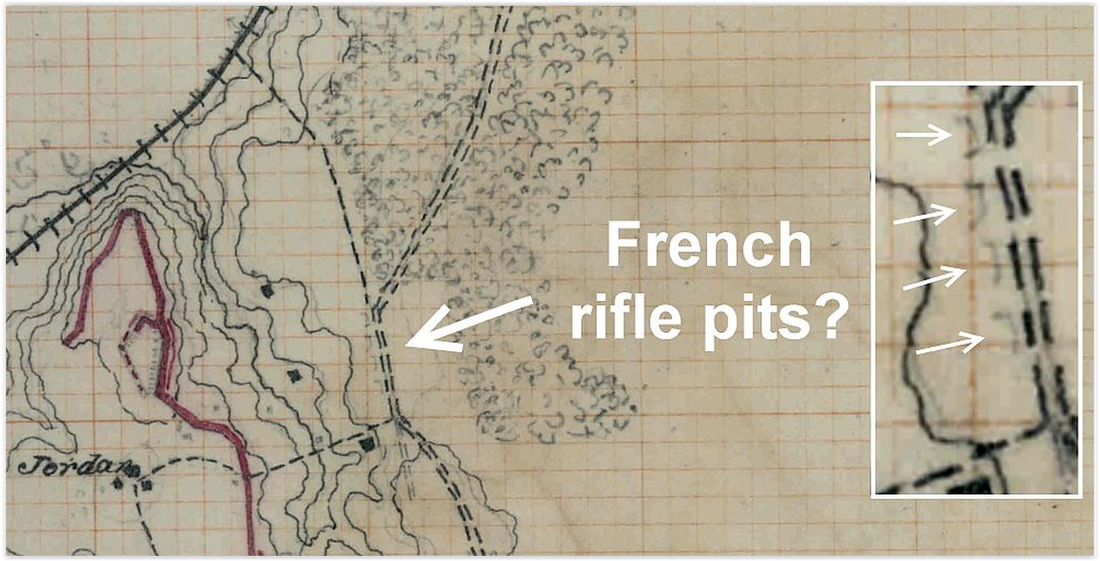

Accounts of the assault on Petersburg on June 15, 1864, include several mentions of "French Rifle Pits" manned by Confederate defenders. Federal commentators clearly found this form of cover to be of interest, although they do not seem to have adopted it. What were these pits? It seems likely that artist Edwin Forbes captured them in the image above. These specific pits no longer exist and the type has not been noted elsewhere on the Petersburg front as of yet.

…General Burnham in his report said; ”I threw my skirmishers forward, and assaulting their line, advancing on the double quick, under a severe musketry and artillery fire. My line dashed across the open field to the enemy’s “French rifle-pits,” which they captured with the entire force that occupied them. Nearly a hundred prisoners were captured here and were hastily sent to the rear, a portion of them guarded by men from the Thirteenth New Hampshire, while others were probably driven to the rear without any guard whatever. Colonel Stevens then moved the line forward, and still encountering a severe fire, they dashed across the open plain, through the ravine and up to the enemy’s formidable works, assaulting and capturing battery No. 5 in a gallant manner.”[1]

…Just before sunset, General Smith moved the 18th Corps and the 2d division of the 10th in three lines upon the enemy’s works. First, a line of skirmishers reached and carried some French rifle pits from which the enemy had continued to fire until they were close upon them; then begged for quarters.[2]

…These pits were so constructed as to afford no protection to the rebels when they got into them. They are called French rifle-pits and are simple excavations shaped like an old fashioned kitchen dusting pan, like the half of a square box sawn through diagonally from corner to corner, with the deep end towards the enemy. The deep end is protection to our pickets, and then, if driven out, the next line has a direct fire through the shallow end upon any who may seek shelter in it.[3]

…The rebels had also constructed what were termed French rifle pits for their skirmishers, which were the first of the kind I had ever seen. They consisted each of an inclined plane about twelve feet wide which reached a depth of about three feet and had a perpendicular wall toward the front. A section of one of them would be like this figure.[4]

[1] New Hampshire in the Great Rebellion, Containing Histories of the Several New Hampshire Regiments, and Biographical Notices of Many of the Prominent Actors in the Civil War of 1861-65. Otis F.R. Waite, Tracy, Chase & Company, Claremont, N.H. 1870; pp 491-492.

[2] History of the Ninety-Seventh Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, During the War of the Rebellion, 1861-65. Isaiah Price, Philadelphia. 1875. Published by the author for subscribers. P 291.

[3] Letters of a War Correspondent. Charles A. Page. 1899. Boston: L. C. Page and Company. P.142.

[4] Days and Events, 1860-1866. Thomas L. Livermore. Houghton Mifflin. 1920. P. 369.

…General Burnham in his report said; ”I threw my skirmishers forward, and assaulting their line, advancing on the double quick, under a severe musketry and artillery fire. My line dashed across the open field to the enemy’s “French rifle-pits,” which they captured with the entire force that occupied them. Nearly a hundred prisoners were captured here and were hastily sent to the rear, a portion of them guarded by men from the Thirteenth New Hampshire, while others were probably driven to the rear without any guard whatever. Colonel Stevens then moved the line forward, and still encountering a severe fire, they dashed across the open plain, through the ravine and up to the enemy’s formidable works, assaulting and capturing battery No. 5 in a gallant manner.”[1]

…Just before sunset, General Smith moved the 18th Corps and the 2d division of the 10th in three lines upon the enemy’s works. First, a line of skirmishers reached and carried some French rifle pits from which the enemy had continued to fire until they were close upon them; then begged for quarters.[2]

…These pits were so constructed as to afford no protection to the rebels when they got into them. They are called French rifle-pits and are simple excavations shaped like an old fashioned kitchen dusting pan, like the half of a square box sawn through diagonally from corner to corner, with the deep end towards the enemy. The deep end is protection to our pickets, and then, if driven out, the next line has a direct fire through the shallow end upon any who may seek shelter in it.[3]

…The rebels had also constructed what were termed French rifle pits for their skirmishers, which were the first of the kind I had ever seen. They consisted each of an inclined plane about twelve feet wide which reached a depth of about three feet and had a perpendicular wall toward the front. A section of one of them would be like this figure.[4]

[1] New Hampshire in the Great Rebellion, Containing Histories of the Several New Hampshire Regiments, and Biographical Notices of Many of the Prominent Actors in the Civil War of 1861-65. Otis F.R. Waite, Tracy, Chase & Company, Claremont, N.H. 1870; pp 491-492.

[2] History of the Ninety-Seventh Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, During the War of the Rebellion, 1861-65. Isaiah Price, Philadelphia. 1875. Published by the author for subscribers. P 291.

[3] Letters of a War Correspondent. Charles A. Page. 1899. Boston: L. C. Page and Company. P.142.

[4] Days and Events, 1860-1866. Thomas L. Livermore. Houghton Mifflin. 1920. P. 369.